How to free your relative from an Egyptian prison

When my brother and father were thrown into Egyptian prisons on the heels of the 2013 military coup that ousted Mohamed Morsi, the country’s first democratically elected president, I was just an average twentysomething young professional living a very stable life in northern Virginia, right outside of America’s capital.

I was still learning how to juggle motherhood, a career in clinical therapy and social responsibilities. Much like others with Arab origins, I had become glued to the television and news reports describing every twist and turn of the turbulent Arab Spring – until one day I found myself doing a panicked sweep of endless footage of bloodied and charred bodies from my couch in my quiet townhouse for what seemed like eternity in search of the familiar faces of my family members.

I could never have imagined then that I would come to learn the art of diplomacy in the hardest manner a layperson could, with their loved ones’ lives hanging in the balance

Days after the protests at Rabaa Square against the coup were violently dispersed, killing nearly one thousand civilians; I received a text from my brother, Mohamed, telling me that he was being arrested. A few weeks after that, my dad was also arrested. I did not know it then, but the quiet life I had lived until that day was over, and the normalcy and structure I had spent almost a decade building quickly faded away.

Almost without a second thought, efforts to secure Mohamed’s release kicked into gear. His friends from near and far immediately reached out asking what they could do to help. I asked each to tell me their area of strength and then mapped out what I thought would be an organised, but short-lived social media effort to get news of his arrest international coverage. I simultaneously contacted the US Embassy in Cairo to get those wheels in motion. And for good measure, I reached out to some brilliant attorneys I knew closely.

I could never have imagined then that I would come to learn the art of diplomacy in the hardest manner a layperson could, with their loved ones’ lives hanging in the balance and dependent on every decision that you make.

Nor could I have imagined that the campaign for Mohamed’s release would become global in scale nor last nearly two whole years, involve an incredible number of truly exceptional people coming together to dedicate much of their time, energy and resources to bringing him home, and that it would fail a hundred times over before it would succeed.

Another young woman from Virginia who also found herself swept up in Egypt’s crackdown against dissenters was Aya Hijazi, who, along and her husband, Mohamed, clung to the hopes and dreams of the 25 January revolution and found themselves in prison. They would come to require intervention of the same magnitude to walk free again after three years of pre-trial detention.

You cannot do it alone

Like us, Aya’s family found amazing, dedicated people to walk alongside them in their quest for justice. There were those, here and just as importantly, in Egypt, who put on their best lawyer hats and poured over case documents, analysing language, documenting due process violations, and consuming political analysis over mediocre Chinese food, koshary, and inordinate amounts of caffeine.

At every low point in the campaign, I would look around me, and consistently find folks who walked, cried, and spent many a sleepless night right alongside me

There were also those who served as the backbone of every legal and diplomatic manoeuvre by organising and mobilising online and in real life to keep the story alive in the minds of those who would otherwise have never known of this particular struggle. There were people who spearheaded local campaigns to assist in the larger efforts. There were some who wrote, sang, and spoke about the plight of our loved ones, and others so paralysed by the magnitude of it all, they stayed away, but silently prayed for relief every chance they got.

Every last one of them mattered more than they will ever know.

I had not known a good majority of them before this ordeal, but now they will forever feel like family. Aya’s family, I am sure, has come to experience the same.

Tell your story. People want to know

As the #FreeSoltan campaign snowballed, I came to realise how important the details were. The team that formed was as dazed as my siblings and I were as we observed the vicious polarisation that gripped Egypt then. Many of the local attorneys with whom we had contact had simply refused to touch the case, citing the “political climate” and either their antipathy towards anti-coup protestors or their fear of retribution from the new military government. The country was deeply divided between those who supported the democratically elected but seemingly incompetent president, and those who opposed him and supported the return of military rule.

Mohamed did not fit in a single box, as he had not been particularly fond of Morsi’s governance, but he also opposed giving up on the dream of democracy

But we were determined not to allow Mohamed’s story to be dictated by the broader political turmoil and knew that we had to cut through the unprecedented amount of political tension to remind people of the real human cost of the events in Egypt.

We also knew we would get shunned by those whose politics demanded people be put in boxes with easy-to-read labels. We knew that Mohamed did not fit in a single box, as he had not been particularly fond of Morsi’s governance, but he also opposed giving up on the dream of democracy in favour of military power. He was from the US and grew up there, but he also was not merely a tourist in Egypt and was proud of his Egyptian heritage and citizenship.

We refused the urge to package his story into digestible bites that would fail to capture the situation properly.

This was no easy task, but I believe authenticity is the only way to truly live a meaningful life. It’s a value I was taught never to compromise, especially in times of adversity. So we all set about telling his story, and sometimes sharing our own, as uncomfortable as it was at our most vulnerable, to help people understand the kind of void Mohamed had left in our lives. I saw Aya’s family do the same.

Sometimes David wins

To my mind, it is not shocking that Mohamed was eventually released. He has not met a person who has not been immediately touched by his kind heart and genuine goodness. The more people learned about his story, the bigger the snowball became and the less hopeless we all felt.

President Obama had been briefed on the developments in Mohamed’s case. He, too, had learned his story, and was moved to help us change it

Still at times, it seemed like all our work would falter in the face of oppressive powers, but shortly after, we would hear something positive, for example that President Obama had been briefed on the developments in Mohamed’s case. He, too, had learned his story, and was moved to help us change it. His was the push we desperately needed, and, as much as I genuinely respect and feel endless gratitude towards him, he did not do it alone. His intervention alone is not what “worked”. So many people before him decided to be a part of someone else’s story.

It was only with the grace of God that a geographically scattered group of people managed to keep walking and picking up other do-gooders along the way even when it seemed like there was nowhere left to go. The president helped us bring him home, but he had simply done what so many others had decided to do in unison: whatever was in their power to bring about justice.

In reality, these fruitful efforts are a departure from the ordinary in diplomatic norms, legal manoeuvring, and public apathy. They defy the odds, and in doing so they inspire hope where once there was none. They ignite a sense of purpose and power, rewrite narratives, and make miraculous tales of faith found in religious traditions like that of David and Goliath come alive in a way no imam, priest or rabbi ever could.

- Hanaa Soltan is a management consultant, a clinical social worker and a human rights advocate.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

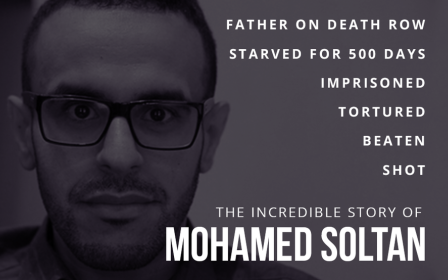

Photo: Mohamed Soltan during an interview at Middle East Eye in London in 2015 (MEE)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].