Egypt’s age of intellectual fascism

All too often, those seeking to deconstruct Egypt look at core issues like the economy, politics or education.

Silence is the goal, fear is the tool and intellectual terrorism, a state in which people think twice before differing with the majority, is the result

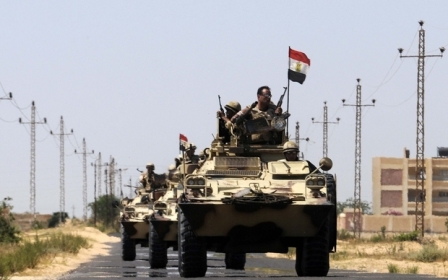

But rather than enumerate the ways in which groups like the Islamic State (IS) are making inroads into the Nile Delta, or how inflation has soared to 31 percent under Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s so-called leadership, we need to look deeper into matters which may seem esoteric. We need to analyse a new phenomenon: a mental condition plaguing the country.

In Egypt, we have a form of intellectual terrorism. It is by the people against the people. This is not merely the rule of "Big Brother", a new form of George Orwell’s 1984, eating away at Egypt’s soul. The damage is done by millions of Little Brothers spreading cancerously through the Egyptian body politic, both within its borders and without.

The army need not enter homes when it has already invaded the minds of its people.

Imagine this scenario

Take any group of Egyptians who gather for a project at work. They could be a cross section of the Egyptian labour force: men and women, Muslim and Christian, young and old, married and single, politicised and apathetic.

Conversations begin, some casual and others less so. Some of these conversations broach sensitive subjects like politics and the economy.

Unbeknownst to the group, someone in its midst excels at what the regime and its security agencies do best: informing police and turning a political difference into an act of treason. But in this case, this person isn’t informing the police. He is twisting - or rather poisoning - the discourse.

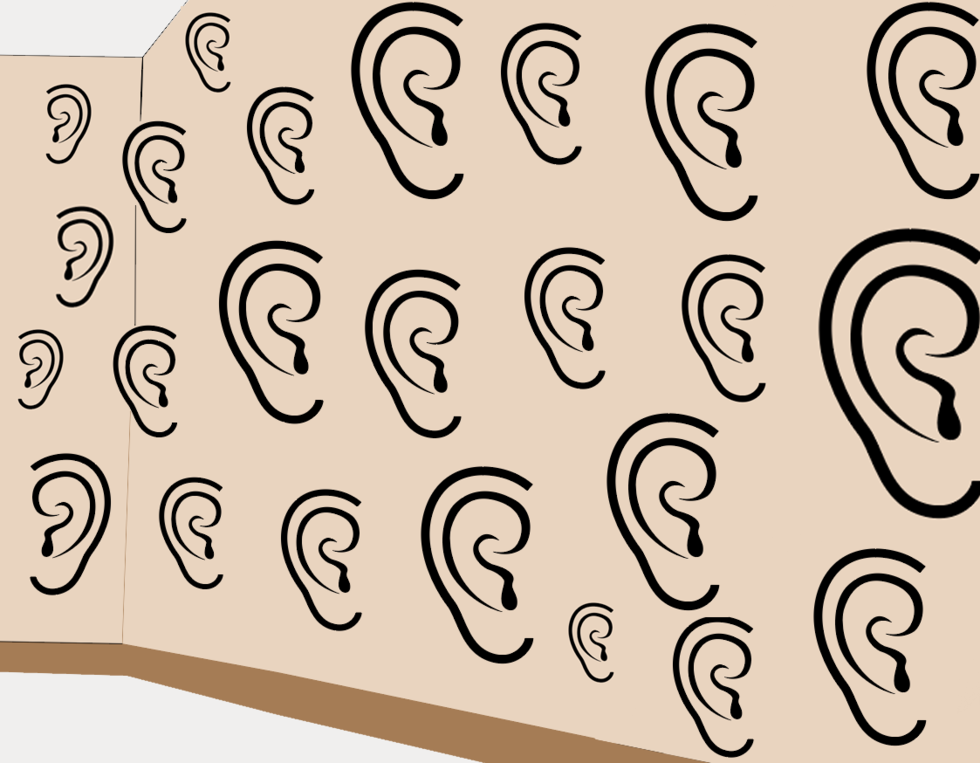

In modern Egypt, walls have often had "ears", but in the days since the revolution of 2011, millions of ears have emerged on the walls among - and between - us. Experiments can either fail or succeed and the signs of failure abound within this micro "society" and Egypt.

Having chosen, at one point in his life, to become an informant out of a need for personal gain or a misguided sense of national duty, the anti-hero among this imagined group has chosen not to divorce himself from Egypt’s police-state mentality. The regime says it is “my way or the highway” and so it is with this man or woman too.

Rather than physical violence, verbal brutality is used by all socio-political camps to silence alternate voices

Man or woman, Muslim or Christian, young or old, anyone who criticises the regime is defined by this informant mentality - with unwavering certainty - as either Muslim Brotherhood or a traitor. One is much the same as the other to such minds.

What never crosses such a mind is the possibility that there are other groups or subgroups in society, outside the Islamist camp, who may be even more critical of the Egyptian president - or multiple groups who, for various reasons, support him.

No less dangerous than this reductive binary logic of being either with us or against us, is the instinctive need to destroy or harm the "other". Though the informant cannot imprison or physically harm the other, his or her aim is to damage the target's social reputation, to disparage and isolate him within this micro society.

Silence is the goal, fear is the tool and intellectual terrorism, a state in which people think twice before differing with the majority, is the result.

Little brother, here, looms as large as a rock atop a pair of lungs, ready to crush the air out of them. In Egypt, and outside of it, the fear of “little brother” is alive and well because military and security institutions have made its return their unwavering mission.

Shushing the other

This phenomenon, part and parcel of a larger fascistic dynamic that has swept Egypt, and to varying degrees, numerous other countries, is not limited to Egyptian work places or homes but all that is identified as Egyptian in cyber space as well.

It abounds on Facebook and Twitter. Rather than physical violence, verbal brutality is used by all socio-political camps to silence alternative voices.

This is not merely limited to the pro-government camp. Revolutionaries, leftists, Islamists, Salafists and secularists are equally guilty of the complex crime of “othering” by shouting down those with whom they disagree, insulting and aggressively attacking - rather than discussing.

While present in certain circles and in some forms, discourse has tragically become the exception rather than the rule. If writers covering Egypt are in the opposition or have remained independent, they expect vitriol in the comments section of every article they pen. I certainly do.

When the level of critique becomes intentionally and systematically toxic - when insult and threat rise to the level of intellectual terrorism - this must be deemed unacceptable.

Write a strong commentary on Egyptian strongman Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the sort that garners attention, and watch: within minutes, a combination of "patriots" and Sisi "electronic armies" will offer the sort of morning greetings that you would censor if your children were present.

Uncomfortable truths

Over the past week, for example, it emerged that ex-president Mohamed Morsi had been denied visitors since his arrest, in stark contrast to Hosni Mubarak, who was treated as royalty in a five-star hotel-style hospital suite, where he was allowed unlimited visits. The discourse about all of this was, naturally, accusatory.

But political barbarism prevailed. Critics hurled insults at Seif while simultaneously defending the brazen human rights violations, saying they should become the modus operandi treatment of “terrorists”.

It is one thing to have a difference of opinion, it is quite another to commit libel and call it free speech, to dehumanise the other because they come bearing uncomfortable truths.

How Egyptians converse today is but a reflection of the violence tens of thousands experience in prisons, hundreds of thousands experience daily in Sinai, and millions have experienced, in one form or another, under military rule, particularly since the coup coloured every aspect of Egyptian life.

A society which limits and attacks free speech within itself is tantamount to nothing less than a society, willfully, self-injecting heroin

A nation with many camps that respectfully and civilly disagree could be called a democracy. But a society which limits and attacks free speech within itself is tantamount to nothing less than a society willfully injecting heroin into its veins.

When your goal is the construction of a fascist cloister that maintains a chokehold on every breath and every opinion, it makes a farce of any conversation about the 2018 presidential elections. If Egyptians can’t hold a contrarian view without fear of multiple levels of retribution, how are they even to consider the inherently democratic notion of elections?

Rescuing ourselves

So why talk about free speech and systematic attacks on it now? Is this about the ability to post what you wish on social media? The answer should be as obvious as an August sun but as winding as the silk road.

One cannot hope to rescue a nation from the precipice without walking back to safety on the bridge of free speech. Egypt is a nation in trouble on multiple fronts, even according to its commander-in-chief, and without transparent national dialogue between its citizens, press, NGOs, parliament and government, hope for real change will remain a mirage at best.

Continue down the current path in which oppositional views are punished, and you undermine what many believe is a judiciary that, at the very least, has been compromised by politicised rulings against both revolutionaries and the Muslim Brotherhood. It can be argued that Sisi is currently punishing the State Council, Egypt’s preeminent legal authority, for its role in declaring the Red Islands as Egyptian.

“Judges are now being threatened with a draft law that would give the president discretionary authority in making some key judicial appointments,” Nathan Brown, professor of political science and international affairs at George Washington University, wrote this month.

Currently, the regime has the judiciary under its menacing telescope. If you undermine the judiciary, then you attack the last bastion operating on behalf of the citizens - theoretically, at least.

What can we do? Listen to one another with an open mind. Anything short of this will cost Egyptians a great deal more than we have already lost

In the past two weeks, Egypt took a giant stride towards becoming the North Korea of the Middle East with 60 members of parliament approving the discussion of a draft law which would require Egyptians to register with the government to use social media. If it were not so tragic, it would be comical.

With each passing day, the continuous exercise of intellectual terrorism by government and citizenry alike shoves Egypt one step closer to the dark cave of authoritarianism.

Those two shadows you see across the table are danger smiling and logic grimacing at Egypt’s refusal of the "other". What can we do? Listen to one another with an open mind. Anything short of this goal will cost Egyptians a great deal more than we have already lost.

- Amr Khalifa is a freelance journalist and analyst recently published in Ahram Online, Mada Masr, The New Arab, Muftah and Daily News Egypt. You can follow him on Twitter@cairo67unedited.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Art by MEE Infographics

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].