Iraqi Kurdish independence: Looming on the horizon?

Last week’s assessment by the head of the US Defence Intelligence Agency that Iraqi-Kurdish independence is a matter of “probably not if but when” followed statements by Kurdish officials that an independence referendum will be held this year once the Islamic State (IS) is defeated in Iraq. Some have been more specific, saying it is likely to take place in the autumn.

It would be a tantalising prospect for Iraqi Kurdish leaders to be credited not just with IS’s defeat in Iraq, but with realising their people’s long-cherished dream of independence

Such statements have naturally led to speculation as to whether the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) will follow through on this repeated pledge. The desire for independence is not in question – the idea of a referendum is supported across the Kurdish political spectrum, and would be overwhelmingly approved by voters.

But there will be potentially major domestic and regional repercussions whether a referendum is held or not. How Iraqi Kurds assess and deal with these repercussions could shape the political – and even geographical – landscape in Iraq and beyond.

It would be a tantalising – perhaps irresistible – prospect for Iraqi Kurdish leaders to be credited not just with IS’s defeat in Iraq, but with realising their people’s long-cherished dream of independence. Their names would be forever remembered in Kurdish history.

There is also widespread suspicion in the region that an independent Kurdish state would be an ally of Israel. This is not unfounded given their historically friendly ties and Israel’s expressed support for Kurdish independence.

After IS is defeated

Iraqi Kurds may be emboldened by the fact that regional opposition to their independence has been expressed in the framework of a need for diplomacy rather than making threats. But that likely represents a hope that diplomacy would be more effective in averting a referendum, and a realisation that for now, Iraqi Kurds are an indispensable force against IS.

If Iraqi Kurdistan’s neighbours sense that a referendum is unavoidable, economic and even military threats cannot be discounted

Their strategic importance in this context will diminish with IS’s defeat. And if Iraqi Kurdistan’s neighbours sense that a referendum is unavoidable, economic and even military threats cannot be discounted, not least because it would likely cover considerable territories captured from IS beyond Iraqi Kurdistan’s recognised boundaries that the KRG refuses to withdraw from, including oil-rich, hotly contested Kirkuk.

Those territories’ Sunni Arab and Turkmen populations, whose abuse by Kurdish forces has been well documented by human rights groups such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, are the most likely to resist militarily.

Such a conflict would create the grievances and security vacuums needed for IS to make a comeback, or for alternative or successor groups to fill the void.

At the mercy of neighbours

Failing a military response, which would carry considerable risks and complications, landlocked Iraqi Kurdistan would be at the economic mercy of its neighbours, particularly Turkey, on which its prosperity largely depends.

A referendum would jeopardise the ties that the KRG has cultivated with Ankara as Turkey has said Kurdish independence is a red line

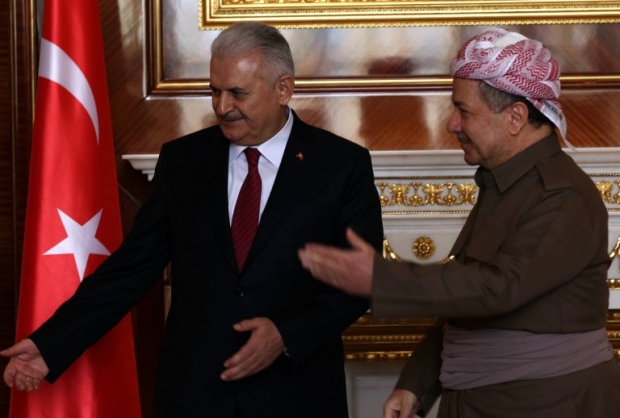

The KRG has managed to cultivate good ties with Ankara, in part to offset its sour relations with Baghdad, primarily over the sharing of oil revenue. An independence referendum would jeopardise those ties as Turkey has said Kurdish independence is a red line.

Meanwhile, the KRG has said a referendum would be followed by talks with Baghdad on the terms of a divorce, rather than immediate independence. But with the central government opposed to a referendum, and with existing tensions likely to be exacerbated by such a vote, it is hard to envision talks achieving a mutually agreed diplomatic outcome after the fact.

And though Iraqi Kurds currently enjoy backing from both Washington and Moscow, they cannot necessarily count on their support for independence. The backing they enjoy comes largely in the context of the war on IS, which is expected to draw to a close this year. Besides, the US and Russia continue to stress their support for Iraq’s territorial integrity, and would not want to alienate close regional allies on account of Kurdish independence.

Damned if you don't

But there are considerable domestic risks in not holding a referendum. There are only so many times Kurdish leaders can whip up separatist sentiment by insisting on a referendum without eventually having to follow through, not least to avoid a public backlash.

“It’s the right of Kurdistan to achieve independence,” KRG President Masoud Barzani said in 2014. Continually delaying a referendum may be interpreted domestically as obstructing that right and cynically manipulating it for political purposes.

Iraqi Kurds postponed their independence referendum in 2014 as a result of the war on IS. The group’s eventual defeat will remove that obstacle, but its removal presents serious challenges and risks that the KRG has so far conveniently avoided grappling with.

A referendum would satisfy historical nationalist ambitions, and could consolidate more than a quarter of a century of successful autonomy. Or it could jeopardise that hard-won success. This brings to mind the old saying: “Be careful what you wish for.”

- Sharif Nashashibi is an award-winning journalist and analyst on Arab affairs. He is a regular contributor to Al Arabiya News, Al Jazeera English, The National, and The Middle East magazine. In 2008, he received an award from the International Media Council "for both facilitating and producing consistently balanced reporting" on the Middle East.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A displaced Iraqi child, who fled the violence in the northern city of Mosul as a result of a planned operation to retake the Iraqi city from the Islamic State, plays with a kite bearing the Kurdish flag at the Hasan Sham camp in the village of Hasan Sham, some 40 kilometres east of Erbil, February 2017. (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].