The Silicon Valley with a heart: How Beirut's techies are helping Syrian refugees

BEIRUT - In Lebanon, new technologies are the talk of the town, as Beirut endeavours to become the Middle East’s new startup hub to help refugees.

“In recent years we have witnessed a growing interest from all the actors of the ecosystem to develop solutions for refugees,” says a spokesperson at the Beirut Digital District, the temple of Lebanese startups.

Ziad Feghali, of Lebanese origin, is one of these new social entrepreneurs. With his gaming company Wixel Studios, he won the competition EduApp4Syria, a challenge set and funded by the Norwegian government to find a way to teach Arabic to Syrian refugee children who had dropped out of school. Yet the long-term goal of the application is to be able to implement it worldwide.

About half of the Syrian refugees in Lebanon are under 18 years old and, according to figures from the Ministry of Education, only 40 percent of them receive formal education.

“There are five worlds which represent five learning blocks. Throughout the game, the children evolve with the character of Antoura, a dog, and are asked to remember things. They have to repeat exercises to access new levels,” the entrepreneur explains.

According to Feghali, the game has been downloaded over 30,000 times since its launch in March.

Smart phone application for vaccines

Vaxy-Nations, an electronic vaccination card, is another idea that blossomed from Lebanon's hackathon, which took place in June 2016.

About 100 Lebanese youth participated in the hackathon that took place in Beirut’s Digital District. They spent three days and three nights trying to find solutions to challenges set by UNHCR, from which several projects emerged.

'Refugees have a very hard time keeping track of their children’s vaccines, so we developed a smartphone application to solve this issue'

- Rami el-Masri, Lebanese co-founder of Vaxy-Nations

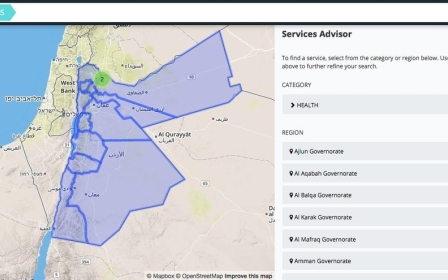

The platform is designed to be very user friendly. Refugees log on and create a profile for their children and the application automatically tells them which vaccines must be done and when. It also geo-localises the nearest medical centre where the injections can be done for free.

Although it was originally designed for Syrian refugees, Vaxy Nation can actually be used by virtually anyone. This aspect of the platform is exactly what has caught the attention of the Lebanese Ministry of Health. After several meetings, negotiations are currently ongoing to determine the precise nature of the future partnership.

Innovative response: a hackathon for refugees

Entrepreneurs are not the only ones seeking opportunities to adapt new technologies to refugee challenges. International institutions such as the United Nations Refugee Agency are beginning to see the advantages of digital innovations as well.

'However, in the last two to three years, things have changed drastically. We have noticed that Syrians learned how to use those technologies while in exile,” he added.

In 2016, UNHCR’s ambitions crossed paths with a young tech savvy New Yorker named Mike Clarke. He was attending a hackathon in Abu Dhabi when he was approached by UNHCR to develop solutions in Lebanon.

“I went on a couple of field visits and I was shocked. It was as if the conditions and experiences of a refugee today and 40 years ago are exactly the same, yet there is a variable that no one is tapping into, which is that most of them have a smartphone and connectivity," Clarke said.

So Clarke suggested to UNHCR that they organise a hackathon in Lebanon, which took place in June last year.

"Lebanon is a unique place for this because you have the know-how and the capacity to execute," says Clarke.

'There is a variable that no one is tapping into, which is that most refugees have a smartphone and connectivity'

-Mike Clarke, techie from New York

KwikSense won the hackathon with a sensor that can be placed in the refugees' tents which automatically detects temperature fluctuations. The data is then sent in real time to software that allows UNHCR to respond directly to abnormal situations.

“For the first time, we will be able to monitor temperature in real time. This new tool will help us define our response better and target our resources towards those who need it the most," says Lisa Abou Khaled, UNHCR spokesperson.

"This is especially important at a time when we are facing funding issues. Technologies such as KwikSense will enable us to make the best use out of the limited resources we have,” she added.

The winning team met at the hackathon for the first time, and includes two engineers, one designer and a high school student.

'The simplicity of how we came together was amazing. We were sitting there not knowing each other and a year later, we have a company and a product'

-Marwan Ghamloush, from the KwikSense team

The team's success was born out of a shared goal. After three days and nights of non-stop work, they came up with the winning technology and the rest is history.

When they deployed a first set of 10 sensors last January, it was the first time the KwikSense team visited a refugee camp.

“We learned a lot from the field visits, from the refugees themselves,” says Georges Najjar, from the KwikSense team

KwikSense just signed a contract with the UNHCR for 300 units. The idea at this stage is to use the device to monitor the cold and adjust UNHCR’s “winterisation programme,” which distributes extra assistance to refugees that are particularly vulnerable to cold weather conditions. The sensor can also be used to detect smoke, water, humidity and structural stability.

A new start

NaTakallam (We speak) is an online platform launched in 2015 that connects Syrian refugees in Beirut to people all over the world who want to learn Arabic via private Skype lessons. The young and multicultural group that founded the project were students at Columbia University in New York. They comprise of American, French, Armenian, Iranian and Lebanese nationalities.

“As a Lebanese who grew up abroad, I always had a complex with the Arabic language. I tried many methods, took private lessons but it was never really what I needed,” says Sara, Lebanese-American co-founder of Natkallam.

"I now have five students and I really like it. It’s like having a conversation with someone; they tell me about their lives, I tell them about mine," says Rusho.

'As a Lebanese who grew up abroad, I always had a complex with the Arabic language'

- Aline Sara, co-founder of NaTkallam

For each hour, Rusho gets paid 10 dollars. NaTakallam has a network of about 60 teachers and 1,200 students, and the Syrian refugees working on the platform have generated over $110,000 of revenue.

For now, UNHCR is not planning on organising a new hackathon, but more entrepreneurs are developing their own solutions to help the Syrian refugees settle.

"[Teaching Arabic to non-speakers] hardly feels like work and it’s a very good solution because the Lebanese often accuse Syrians of stealing their jobs; but with this platform, we really feel that there is a place for us,” says Rusho.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].