Gaddafi, the Manchester attack and the lesson British leaders must still learn

A few wise officers in MI6, Britain’s foreign intelligence agency, warned of the dangers of invading Iraq.

The then-head of MI5, Britain’s domestic security service, warned that an invasion would increase the risk of radicalising Muslims and the terrorist threat. Britain’s Joint Intelligence Committee, which brings together the heads of all the country’s security and intelligence agencies, stressed that terrorism, not Saddam Hussein, was the biggest threat to the safety of the British public.

After the mayhem and violence provoked by the invasion of Iraq, leading British politicians said they had learned the lesson. They had not

They were ignored. After the mayhem and violence provoked by that invasion, leading British politicians said they had learned the lesson. They had not. The next time it was senior military figures who warned of the dangers. They were ignored. Britain joined France in bombing Libya, with Nato support and those of some Arab countries.

Muammar Gaddafi, once a friend of Britain, just like Saddam Hussein, had become the enemy. And the enemy’s enemy seemed to become friends again, or at least tolerated, no matter what kind of hardline Islamism or violent, anti-Western views they espoused.

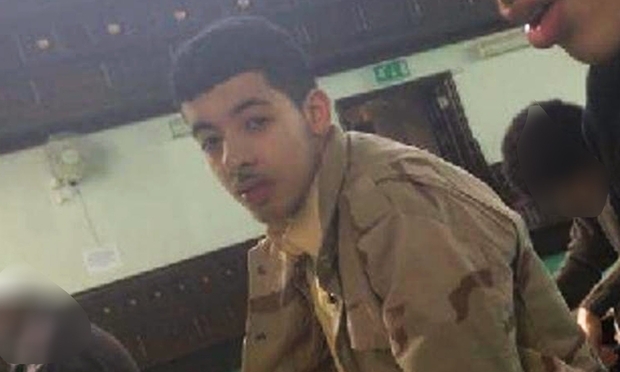

The spotlight turned again on Libya when the Manchester arena suicide bomber was identified as Salman Abedi.

Gaddafi the enemy

For a long time, Gaddafi was the enemy, the dictator who for years provided the IRA with weapons and Semtex explosives, whose agents blew up the US airliner over Lockerbie, and killed Yvonne Fletcher, the British policewoman overseeing the demonstration outside the Libyan People’s Bureau in central London.

For the British, Gaddafi indeed seemed to be foreign enemy number one.

This gave credibility to claims by David Shayler, a renegade MI5 officer, that MI6 was involved in a plot to assassinate Gaddafi. In 1996, members of rebel groups attacked Gaddafi's motorcade near the city of Sirte. Robin Cook, then foreign secretary, described reports of MI6 involvement in the plot as "pure fantasy". The response of Foreign Office officials was more nuanced. "We have never denied that we knew of plots against Gaddafi," they said.

MI6’s source was code-named Tunworth, who at one point was given £30,000 by British intelligence officers. MI6 did have advance knowledge of an attempt on Gaddafi’s life, including, it seems, an attack in Sirte in March 1996 in which a number of militants, members of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), were killed.

I have not seen direct evidence of MI6 plotting with the LIFG. What is clear is that a number of the group’s supporters – and future supporters – travelled to the UK and stayed there. One was Abedi’s father, Ramadan. Though he has denied being a member of LIFG and opposed violence, Ramadan has commended the group.

It is clear from documents discovered after a Nato bombing strike on Tripoli in 2011 that MI5 and MI6 knew about the activities of LIFG supporters in Britain and the potential threat they posed, to both Britain and Gaddafi. The destruction of the offices of Moussa Koussa, Gaddafi’s intelligence chief, produced what must go down as one of the most extraordinary – and for Britain’s security and intelligence agencies, most damaging – disclosure of documents to get into the hands of journalists.

They were seized, respectively, in Malaysia and Hong Kong, tied up by CIA agents and flown to Tripoli, the Libyan capital, where they were jailed and tortured. MI5 sent Gaddafi’s security and intelligence agents questions they should ask Belhaj and Al-Saadi about LIFG activities in Britain and elsewhere.

The documents also showed that MI5 agreed that Gaddafi’s agents would make “approaches” to known dissidents in London and Manchester, and that they did succeed in getting some of them to cooperate.

Gaddafi the friend

From being a villain, Muammar Gaddafi became a close friend.

After a ship carrying nuclear-related material to Libya was seized in the Mediterranean, Gaddafi – already offering compensation to the families of Yvonne Fletcher and the Lockerbie victims and his country already suffering from heavy sanctions - agreed to give up his nuclear and chemical weapons programme.

Allen’s letter to Koussa helped to lead the way to Blair’s “deal in the desert” and a £15bn oil drilling contract for BP with Libya. Jack Straw, the former UK foreign secretary, later acknowledged trade and oil played a part in the 2009 decision to include Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, the only person convicted of the Lockerbie bombing, in a prisoner transfer agreement with Libya.

In a relationship full of bitter irony, Blair later defended his relationship with Gaddafi on the grounds that it contributed to the fight against terrorism.

Villain once more

Then, in 2011 and at the start of the Arab Spring, with Gaddafi’s threats to protesters, notably in Benghazi, the Libyan leader was a villain once more. His enemies were Britain’s friends.

MI6 and Britain’s special forces were prepared to support anyone, including hardline Islamist groups, some funded by Qatar, who opposed Gaddafi. Middle East Eye has reported how the British government allowed the participation of Libyan dissidents and exiles, including Libyans who had been subjected to anti-terrorist control orders.

We all know there is no such thing as total security, that some terrorists are always likely to slip through the net.

But the struggle against terrorists and Islamist-inspired, violent militants cannot be helped by Western governments playing fast and loose with dictators and authoritarian regimes in the way Britain has done with Libya. Serious questions remain about UK-Libyan connections. They need to be answered, and in light of the Manchester arena bombing, urgently.

- Richard Norton-Taylor is a former security and defence editor at the Guardian. His books include In Defence of the Realm? The case for Accountable Security and Intelligence Services and Truth is A Difficult Concept: Inside the Scott Inquiry. He has written a number of award-winning plays, including Half the Picture, The Colour of Justice, Justifying War, Bloody Sunday, which won an Olivier theatre award, Called to Account, and Chilcot. He is on the board of Liberty, the National Council for Civil Liberties. He has twice won Freedom of Information Campaign awards.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi salutes his soldiers during a five-hour military parade in Tripoli in September 1999 to mark the 30th anniversary of the Libyan Revolution that brought him to power (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].