Bringing up baby in a Syrian jail: I covered his ears to block out the screams

His mother can’t recall the exact date, all she knows is that they were in the Adra jail outside Damascus.

“I didn't recognise whether it was day or night,” she says. “We weren't allowed to leave, for the bathroom or for a shower.”

There wasn’t much legroom in the dark and airless room that she and her son shared with their fellow prisoners.

She does not reveal her true identity for fear of her life and asks to be referred to as "Om Omar" - which translates into English as "mother of Omar".

“I was on one side and another girl named Marwa was in front of me, about one-and-a-half metres away. I would walk with him, using my hands, towards her. Then we would swap over.”

When Omar fell, his mother would catch him. Slowly but surely, with uncertain steps to begin with, he found the confidence to walk.

“He was strong,” she says. “He was the only baby there. It made the other prisoners happy to look at him. It was one happy time amid the darkness of this prison and its cruel guards.”

Omar spent the early years of his life in a Syrian jail while his mother was tortured. This is their story.

‘It wasn’t the life I expected’

When she was younger Om Omar, now 38 and originally from Deir ez-Zor in eastern Syria, would imagine what life might hold for her.

“Like every woman in the world, I would dream of having babies,” she recalls, “of raising my family in a good decent house like every family in the world.

“When I was teenager, I was so obsessed with babies, taking care of our neighbours’ babies and friends’ when they used to visit my mother. I dreamt I would have at least one, and I did. But unfortunately it wasn't the life I expected."

When conflict broke out, the city, the country’s second largest, rapidly became a focus for protests against the government of President Bashar al-Assad.

Khalid lived in the rebel-held eastern neighbourhoods: He joined the Free Syrian Army but was killed by mortar fire during a battle against government forces in August 2013. He was 44 and had been married to Om Omar for seven years.

Omar was born in March 2014 in Eza’a in western Aleppo. Father and son never met.

Om Omar was widowed, alone and had no contact with her family, who disapproved of the couple’s activism against the government. She had already been detained in 2011 and 2013 for her opposition, the second time for three days.

“I didn't bother trying to talk to them or convince them,” she says. “I continued with my activism.”

Her life now, Om Omar says, is like that of a single woman. But while she grieved for the loss of her husband, she also worries for the future of herself and her son.

The neighbourhood, which was a frequent haunt for snipers, provided a corridor between the divided city before it became a no-go zone after clashes in 2014.

Om Omar knew that her activism carried a high risk - but still regarded it as her duty. “I was reckless, yes. But I had to do it and don't regret it. I had a priority, which was the sick people who needed the medicine.”

She thought those hopes of her younger years would never come true. “This was my life after giving birth and Khalid's death,” she says. “I was struggling to breastfeed my baby because of the intensity and pressure I was living under at that time.”

And then, in September 2014, Om Omar's life took another turn for the worse.

One night, five men from a government intelligence agency burst into her home while she and Omar were asleep. She believes they were betrayed by a neighbour.

They searched the house, swore at Om Omar and took away packets of medicine.

They accused her of helping injured terrorists with medical supplies.

Om Omar denied the allegations and refused to provide the names of her social circle, lest they also fall under suspicion and face arrest. When she began to scream, the men put guns to her head. “The raid was the straw that broke the camel's back," she recalls.

She and Omar were then taken to the agency HQ in Damascus, more than 200 miles away where, Om Omar says, “the horror began”.

Om Omar was blindfolded when she first entered the state’s prison system – but she could already detect the “stinky, dirty smell” that would permeate her life during the coming years.

“I felt shocked,” she says. “I was shaking with my crying baby, wondering what my or his destiny would be.”

There was no ventilation: instead prisoners resorted to digging holes through the walls to try and let in air

Mother and son were to spend nearly a month there, then shuttled between other prisons across the capital, including that at Al-fiha'a. “They took the baby from me on the first night, to put pressure on me, then they gave him back after the first interrogation."

Omar was two months old at the time.

“When I entered, there was water on the ground that smelled terrible," she says. "The walls were full of words, the names of previous prisoners who used be in the same room. It was like an abandoned basement that had not been fixed for ages. I could barely walk because I felt dizzy. I had not slept and it was night.”

The room was crammed with other women. There was no ventilation: Instead, prisoners resorted to digging holes through the walls to try and let in air. Throughout her first night, Om Omar could hear the sounds of men and women screaming.

Tell me everything - or you will never see your baby

For her first interrogation Om Omar was led into a room. Her hands were bound. Her eyes were blindfolded. She was hit with every step she took.

The interrogator asked her about her family, about her husband, about her work. She was accused of taking medical supplies to help the Free Syrian Army.

When Om Omar started to answer, her interrogator hit her on the head. "Stop lying and tell me the truth about your work and husband!” she recalls him shouting.

"In the beginning I was utterly terrified because of the torture and beating,” Om Omar says. “I was afraid of being raped, or killed.”

And then there was the threat to Omar. Human rights groups have documented how the Assad government has tortured and killed children to punish, or extract information from, their families.

In the days after her first interrogation, Om Omar was left in an overcrowded room. Omar cried all the time. The guards paid no attention to her appeals for food or baby supplies. Eventually she had to improvise diapers by ripping up pieces of old clothing.

Soon the torture sessions became a regular part of prison life. “When I came back after every interrogation, I held my son and cried,” Om Omar says. “So did he.”

Prisoners call this method 'hanging', according to a report, inflicting 'awful pain, ligament rupture and semi-permanent paralysis in the hands'

Om Omar also had to face torture sessions at night, the first after she had been detained for a week. She recalls how she handed Omar to one of the friends she had made in prison before she was dragged to a large room and faced, as she puts it, by a “fat middle-age man, with a big stick in his hand. He started to come close to me, and said: ‘Tell me everything or you will never return to see your baby tonight.' I said nothing. I was shocked.”

The man screamed at Om Omar to confess, then beat her to the ground. She was covered in blood and already barely able to stand. Later he returned with an accomplice and a rope, which he hung from the ceiling. Om Omar was then suspended by her bound hands, her feet only just touching the ground.

What she describes is a common and well-documented form of torture practised by the Assad regime. Prisoners call this method "shabeh" (hanging), according to a report released by the Violations Documentation Centre in Syria in September 2013, which inflicts “awful pain, ligament rupture and semi-permanent paralysis in the hands".

Om Omar was left strung up for hours. Then, more questions. Still, she said nothing. “I knew that if I said anything then they would keep on torturing me and increase the level and the brutality of the torture.”

This treatment continued for almost two months. She recalls fellow detainees being repeatedly raped and tortured, dying from hanging or lack of medical treatment.

At one point Om Omar was moved to the notorious Branch 215 where, the VDC reported, up to 70 prisoners would be crammed into a cell four metres by four metres. Consistent testimony from survivors describes how prisoners were starved or thrown onto the floor “swimming in a pool of blood and pus that oozes out of their bodies due to the lack of sanitisers and hygienic conditions”.In December 2015, Human Rights Watch reported that at least 3,532 detainees had died at the centre, based on evidence smuggled out of Syria, although the group regards this figure as an underestimate.

To many Syrians, the centre is simply known as “the Branch of Death”.

Explaining the world to someone who has never seen it

In December 2014, Om Omar and Omar were taken to Adra prison, where they were to spend the rest of their imprisonment.

About a year after they were first arrested, Om Omar started telling Omar about the outside world, “about real life, about parks, school and so on".

Omar began to form words when he was nearly 18 months old and his mother was teaching him parts of the Quran. “His first word was 'mommy', which he said very roughly,” she recalls. Teaching her son the word "daddy" caused great sadness - but Om Omar wanted Omar to remember that he had a father.

The toddler's progress had a positive effect on the other prisoners. “The atmosphere in the jail room was happy, despite the desperate conditions we were all living under,” Om Omar says. “Everyone gave Omar a kiss. But then the guards heard that it was getting noisy and started to hit the metal door quite hard, which made Omar cry.

“They didn't supply me with milk or any other items that I needed for my newborn baby. His size and weight were low because of the lack of food when he was meant to be growing.

“Once he got an infection because of the hot weather in the prison. It was so incredibly bad, he couldn't sleep, or calm down, until the prisoners came and took me to the prison doctor and gave him medicine.” Still Omar did not get better. Eventually some friends "had some leaves which we put in water and after half an hour he fell into a deep sleep".

Prison was Omar’s home. Sometimes he might toy with a blanket – but it was a world where he was too young to make friends.

“That broke my heart,” his mother says, “because I looked back at when I was pregnant with him and the life I dreamt of him having in the future. Of buying his small bed and toys and everything any mother dreams of getting for her baby.

“It's heart-breaking. It made me cry many times at night, thinking of a bright future with his dad, who is dead already.” Om Omar would sing to lull her son to sleep or else “start to tell him short stories about the Prophet Muhammad and his fellowship, trying to reassure him”.

But sometimes Omar could not sleep because the weather was too hot or too cold - or because of the sounds of torture from the prison yard.

“I was covering his ears to prevent these voices from entering his head,” Om Omar says. “I couldn't do it in the end, he was crying so intensely when he heard these voices.”

For support, Om Omar clung to her faith and the struggles of the prophet as well as the love of her son and encouragement from fellow prisoners.

“Many times I burst into tears out of pressure and desperation. I thought I would die here and never get out to live a normal life and in a house. They were the worst days of my life.

“I took an oath that I wouldn't give up, because of Omar, so long as he's with me... for him and his beloved dead father, who left me a piece of him. I'll be taking care of him for the rest of my life."

How Omar was reborn

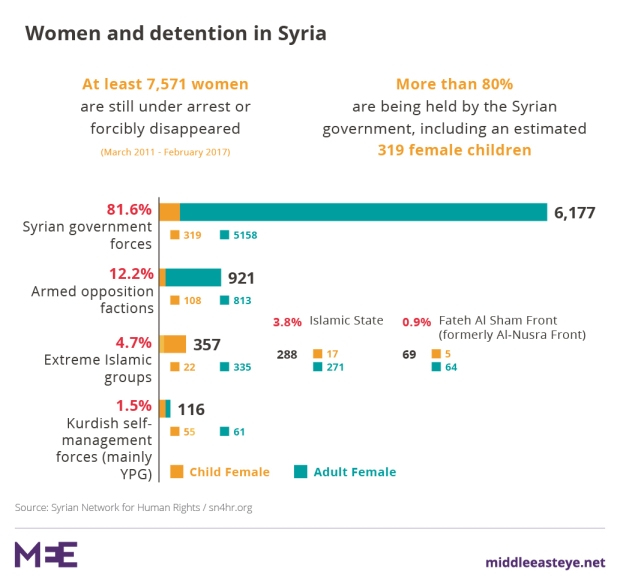

And then Om Omar and Omar were free. On 8 February 2017, the government cut a deal with opposition forces that resulted in the release of 50 women from government prisons. As part of the agreement, Om Omar had to pay a judge just under $6,000.

Her relief was uncontainable, she recalls, as she told Omar that they would return home and see the sun, people, children. “I cried a lot,” she says. “It was unbelievable, the reaction on his face. He was crying and happy.”

Om Omar now lives with a friend in the countryside in Idlib and is in contact again with her sister, with whom she lost touch while she was imprisoned. She also has space to reflect on what her years in detention did to her and her son, who is comprehending the outside world for the first time.

"One time he asked ‘Are we in heaven, Mum?' because he saw birds and cats and wanted to know,” she says. “You can imagine how surprised he was when he was realised it was the actual world.”

Omar, who now sports short brown hair, lives at a rehabilitation centre with other children in an attempt to reintegrate him back into society. His mother visits her son as much as she can.

Ahmad Khaldon, assistant manager at the facility, said that Om Omar’s case is not that unusual amid a conflict that has left more than 470,000 people dead, according to the Syrian Centre for Policy Research.

“They have been through similar circumstances, of struggling from the aftermath of the war and its physiological effects and losing their childhood," he says. "We try to give them the proper atmosphere of bringing up a family, which they miss back in their home.”

At first Omar had problems interacting with other children, including fighting, but is now more relaxed and playing and eating. Om Omar says: “It’s like he's born again, seeing everything new and adapting to aspects of his new life. He has flashbacks about what and how it was like in the prison, but he's got better recently."

He is forming new memories of things he had never seen before, of animals, buildings, cars and food.

Will Om Omar tell Omar the full story of those years spent in prison?

“I will tell him what happened,” his mother says. “I won't lie to him ever. He will know from the internet what has happened to his country, his land, his dad and how death and devastation were brought to his land.

“The media tells people everything, so I would rather tell him myself. I will tell him how they were torturing men and women. And how hard it was to carry on and be positive and have a dream.”

Additional reporting by Nick Hunt

Zouhir Al-Shimale is an online and photo journalist from Aleppo, Syria. Aside from Middle East Eye, he has also contributed to Al Jazeera English, ZeitOnline, The New Arab and The National.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Om Omar and Om after their release (Zouhir Al Shimale/MEE)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].