July 3: The end of one revolution and the start of another

It is no coincidence that the deadline Qatar was given to comply with Saudi Arabia’s 13 demands fell on 3 July, the fourth anniversary of the military coup in Egypt that ousted the country’s first democratically elected president.

The link between the two days was made explicit by propagandists for the Saudi and Emirati regimes. On 2 July, Dhahi Khalfan Tamim, the former police chief of Dubai, tweeted: “On 3 July Morsi was ousted. On 3 July Qatar will be ousted. Is it a coincidence?”

The week before, Abdulrahman al-Rasheed, the former general manager of the Saudi-owned Al Arabiya TV, wrote of Qatar: "It is threatening and warning that the confrontation will be similar to what happened at the 'Safwan tent' but we fear for Doha as it may be like the 'Rabaa Square!'"

When an ally commits acts like the massacre of Rabaa square in August 2013 that "likely amounted to crimes against humanity” - these are Human Rights Watch’s words not mine - the normal reaction is to distance yourself from it.

But these are not normal times. The sponsors of the coup in Egypt not only boast about what happened, but also threaten to use the same tactics on their disobedient Gulf neighbour.

They have become drunk with power. If they wield a big stick, they expect everyone to cower. Bahrain did. Qatar, so far, has not.

The final chapter

July 3, 2013 was a pivotal event for all sides. For the youth, and the forces which toppled two dictators in Tunisia and Egypt, it was a crushing blow.

For the Gulf monarchies who financed Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, it was the start of the counter-revolution that would shore up their absolute power, kick free elections or any form of parliamentary accountability into the next decade, and leave them with their wealth.

The attempted coup in Turkey last year and the campaign against Qatar today marks nothing less than the final chapter of an operation started four years ago

The attempted coup in Turkey last year and the campaign against Qatar today marks nothing less than the final chapter of an operation started four years ago.

Qatar supported the political opposition in Egypt and elsewhere in the region. It gave the Arab Spring a voice, through the reporting of Al Jazeera. Silencing Qatar is thus central to the success of the whole four-year operation. This is the driving force behind the blockade and sanctions today.

The more Saudi, the UAE and Egypt insist that their campaign is about ending the funding of terrorists, the more examples come to light of the collusion of their states with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) group, evidence which they are now keen to sweep under the table.

I have already written about the release of 1,239 inmates on death row by Prince Bandar bin Sultan, on condition they “go to jihad in Syria”, according to a Saudi Interior Ministry document dated 17 April 2012.

On Wednesday, Middle East Eye published UN documents, dated 3 February this year, in which Egypt placed a hold on a US proposal to add IS entities in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Libya and Afghanistan-Pakistan to the UN list of sanctioned groups and individuals. They stopped it again in May.

As Madawi al-Rasheed, visiting professor at the Middle East Centre at LSE said, this was "a classic case" of Saudi Arabia not wanting to draw attention to its own terrorism problem.

Bring back Mubarak

Four years ago, the Egyptians who poured onto the streets on 30 June 2013 to demand that Morsi step down looked to the army and to Sisi as a source of stability. Today, however, Egypt is less stable, weaker and poorer by every parameter.

When the cry now is to bring back Mubarak - or rather his son Gamal - it is not an ironic one

Between 30 and 40 percent of the country is living on $2 a day or less. In May, inflation rose to 30 percent, the highest in three decades. Fuel prices have increased by 200 percent in three years. On 3 July 2013, the US dollar was worth less than six Egyptian pounds. Today, it is worth more than 18. Even the official rate of unemployment - 12.4 percent - is spiralling and the real rate is much higher.

This for a country that has been given at least $50bn from three Gulf States, Saudis, UAE and Kuwait, and a further $12bn bailout from the IMF.

Four years on, the human cost of Sisi’s iron hand is high. The following is a snapshot of his repression, from figures drawn from the Arab Organisation for Human Rights: 2,934 extrajudicial killings, 58,966 arbitrary detentions of whom over 1,000 are under age; 30,177 court sentences; 6,863 military trials; eight politically motivated executions; 11 more on death row. In Sinai, 3,446 civilians have been killed and 5,766 detained, and more than 2,500 houses demolished to establish a buffer zone on the border with Gaza.

Today’s enemy of the state is a prominent human rights lawyer, Khalid Ali, who shot to prominence over his defence of a case in January against a government plan to transfer two uninhabited Red Sea islands to Saudi Arabia. He has been detained for “offending public decency” as have eight members of his Bread and Freedom Party for “misusing social media to incite against the state" and "insulting the president," according to the party's legal advisor.

When the cry now is to bring back Mubarak, or rather his son Gamal, it is not an ironic one. Mubarak is remembered as a competent oligarch in comparison to the venal, stupid, and blood-stained Sisi.

The other side of the story

Egypt today is on its knees, so weakened by misrule it may never again recover. But this is only one side of the story.

The major fault line in the Arab world, which the uprisings of 2011 could not surmount, is created by the distribution of wealth. With the exception of oil rich Iraq and Algeria, both crippled by clientism and corruption, the wealth is on one side of the Arab world and the masses are on the other. Without the rich part of the Arab world investing its wealth in its people, the Arab spring was doomed. This is felt as keenly today as it was in 2011.

The central question that the US government has been asking itself about its Saudi ally: just how much is the House of Saud creaming off?

To look at the wealthiest Arab countries is to be aghast at how much of it there is and on whom it is spent. The rankings of sovereign wealth funds tell an interesting story. Firstly that there is immense wealth - the sovereign wealths fund of the GCC amount to $2.8 trillion. At $320bn, Qatar is a modest player, although its population is tiny. Saudi, UAE, Kuwait and Bahrain have assets valued at $2.53 trillion.

Look closer and there is something that does not make sense about the relative size of these funds. The funds held by six Emirati sovereign funds amount to just under $1.3 trillion while the two top Saudi funds are valued at $679bn, only half that. You would expect it to be the other way round. Five extended families in the Middle East own about 60 percent of the world’s oil and the Saud family controls more than one-third of that.

Follow the Saudi money

This is a puzzle and the answer may lie in the black hole of Saudi’s state accounting, something that lawyers on the New York and London stock exchanges will be interested in investigating now that up to five percent of Aramco, the Saudi state oil company, will be up for sale.

In 2003, Robert Baer, a former CIA man who wrote a book on the subject, estimated the size of the family to be 30,000 of whom, he wrote then, between 10,000 and 12,000 were on royal stipends ranging from $800 to $270,000 a month. These figures are 14-years-old and would have gone up considerably since.

Huge sums of money are disappearing from Saudi state coffers - an average of $133bn annually

The cost of funding the Saud family today can be glimpsed by the magically changing numbers for government revenue provided the General Authority for Statistics (GAS) yearbook. In its scrutiny of the changing figures, the Arab Digest published in May claims that huge sums of money are disappearing from the state coffers - an average of $133bn annually.

The transparency that is required on the New York and London stock exchanges about the forthcoming sale of shares in Aramco is shedding an unwelcome spotlight on the central question that the US government has been asking itself about its Saudi ally - just how much is the House of Saud creaming off?

Taxing foreign workers

They are certainly not spending this money on their people, and are scrambling to find other sources of revenue, such as foreign workers. Some 11 million foreign workers are going to be forced to pay in advance for their dependents to live in the country, as a condition of getting their entry visa. Each foreigner will pay $319 for each dependent this year, which will rise to $1,070 by 2020.

Contrary to the image, most of these are not rich expat Brits, but low-paid workers from the Arab world and the Indian subcontinent. Rather than pay these sums, they will send their families back, as they will their salaries. The Saudi state will lose twice over.

The net external assets fell by $36bn in the first quarter of this year, and have dropped from $737bn in August 2014 to $529bn in December 2016.

This is evidence of corruption on a vast scale and suggests that the state coffers are haemorrhaging funds to keep the royal family in the life style to which they have grown accustomed.

The revolution cometh

Now just imagine if in 2011, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates, the richest countries of the Arab world, had taken a different decision. Imagine that instead of investing in a counter-revolution and another decade of repression, they had chosen to invest in democracy and in people.

For a culture that uses the word brother a lot, fraternity is in short supply

Imagine that when governments were elected after the first free elections the region had known, they didn't need donor conferences. Or a Marshall plan. The money was already there. All it needed was for one part of the Arab world to have faith in and invest in the other part. For a culture that uses the word brother a lot, fraternity is in short supply.

The Saudis have committed themselves to spend up to $500bn on US arms sales.Donald Trump is very grateful, so thankful in fact that he is cutting his aid to Tunisia, the only Arab state where there are real elections, a real parliament and a functioning although faltering democracy. It is desperately short of foreign investment. Instead of getting an insignificant $177m, it will now get a paltry $54.4m. US aid to the autocratic regimes of Egypt and Jordan only marginally decreases, while Israel continues to get its $3.1billion. As an expression of American values under Trump, these figures are hard to beat.

The rich and powerful chose instead to invest in repression. Four years on, millions of Sunnis are homeless. Mosul, Iraq’s second city, is in ruins. Cholera has broken out in Yemen on Saudi’s doorstep. Devastated by a 27-month war conducted by the Saudi-led coalition, at least 10,000 people have been killed, 3.1 million people are internally displaced and 14.1 million are food insecure.

Does this carnage make the kingdom’s southern border any more secure? Do Yemenis feel beholden to the Saudis after what they have experienced?

As with Egypt, so with the region as a whole. At the very point in which the Saudis and Emiratis seem victorious, they are sowing the seeds for a huge new revolutionary wave to come. This time it will not be based on democracy, the rule of law and non-violence. Nor will it be self-restrained or controllable. But it is coming.

- David Hearst is editor-in-chief of Middle East Eye. He was chief foreign leader writer of The Guardian, former Associate Foreign Editor, European Editor, Moscow Bureau Chief, European Correspondent, and Ireland Correspondent. He joined The Guardian from The Scotsman, where he was education correspondent.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

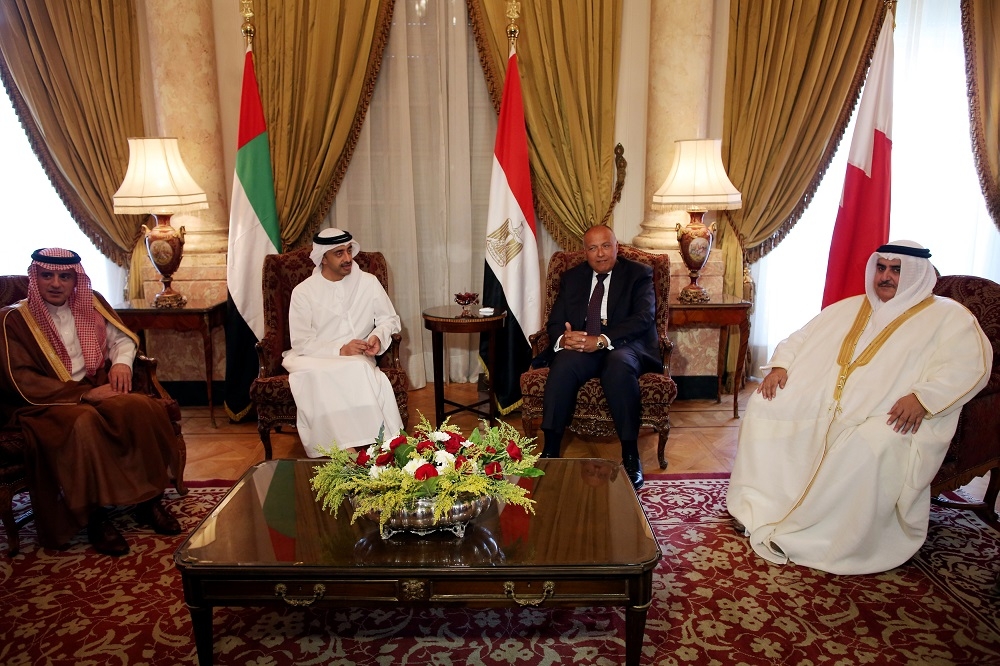

Photo: (L-R) Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir, UAE Foreign Minister Abdullah Zayed bin al-Nayhan, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh al-Shoukry and Bahraini Foreign Minister Khalid bin Ahmed al-Khalifa in Cairo on 5 July (Reuters)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].