Welcome to Ouzville: Art project brings hope and controversy to Beirut ghetto

BEIRUT - Ask most Lebanese about the Ouzai neighbourhood and they’ll likely frown. This area, located in the southern suburbs of Beirut, does not have the best reputation.

According to common belief, it is a Hezbollah stronghold, a place of extreme poverty and illegal trafficking – especially for car parts. Physically the place looks like a slum, a forgotten territory on the outskirts of the capital.

Yet, for one businessman, Ouzai is a place to build dreams.

Breaking stereotypes

Ayad Nasser was born in Ouzai before finding success at home and overseas in real estate with his property company.

'With colours and paintings, we are reviving the streets and bringing joy'

- Ayad Nasser, businessman

But he has now settled back in Lebanon with one goal: he wants to break the stereotypes about his old neighbourhood and turn it into an enticing destination for all.

To do so, Nasser invested $120,000 into a project he calls “Ouzville”. With his team, he invites Lebanese and international artists to paint giant murals over the walls of the neglected buildings. They also gathered a team of volunteers to clean the street and the beach of rubbish.

“I wanted to go back to my roots and do something for my country. With colours and paintings, we are reviving the streets and bringing joy,” says Nasser, as he takes MEE on a tour.

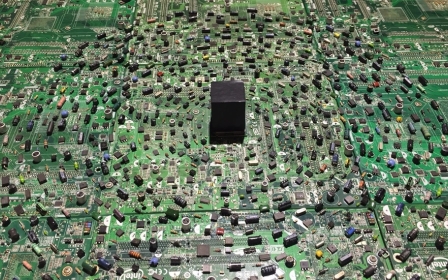

In a perimeter of about one square kilometre, most buildings carry murals or at least a touch of colour. There are drawings of flowers, fish and abstract characters. Other murals include Arabic calligraphy and graffiti. The Lebanese calligraffiti and street art crew Ashekman painted the first building.

“I immediately thought it was going to be a cool initiative for the country. We need positivity,” says Omar Kabbani, a member of the crew.

With Ouzville, Nasser wants to put Ouzai on the touristic map of Lebanon.

'Ouzai... is the first image you get of Lebanon and I want it to be positive'

- Ayad Nasser, businessman

“When you land at the Beirut airport, Ouzai is the one thing you see from the plane. It is the first image you get of Lebanon and I want it to be positive,” he says.

The residents of Ouzai say that the project brings a lot of visitors to the once discarded slum. With time, they hope this can impact the local economy.

“The other day I saw a woman walking down the road. She said that she came to see the paintings, can you imagine?” says Joumana Younes Safieddine, who lives in one of the houses recently painted pink by Nassar’s team.

A little further off, a new grocery store has just opened.

“We now have visitors, tourists and the restaurant nearby needs more supplies so I started a small business,” says Jamal Brahim Tabbara, who runs the shop.

In a matter of weeks after the launch of the project, “Ouzville” was all over social and traditional media. The reviews were supportive and Nasser is already thinking of a crowdfunding campaign to expand the project to another part of the neighbourhood.

Smoke and mirrors

Yet on the ground, “Ouzville” also raised controversy. A few streets away from Nasser’s current area of operations, some people are not so enthusiastic about the colourful murals.

'I don’t need artists, I need a job'

- Ali, local resident

“This is all for show, they are taking us for fools. My life is very hard, I have no money to support my family,” says Ali, a 29-year-old resident of Ouzai.

“I don’t need artists, I need a job,” he adds.

Mona Harb, a professor of urban studies and politics at the American University of Beirut, who has worked extensively on the southern suburbs of Beirut, shares the same analysis.

“For me this is a ‘feelgood project’. It looks nice but it does not offer dwellers much. People need infrastructure and jobs, not paint over their walls,” she says. “With all the money he invested, Nasser could have fixed real problems.”

“But who is this project for? People who watch Ouzai from an airplane? Tourists who want to see poverty? I don’t think poverty is ugly,” she adds.

Nasser is aware of such criticism, but for him fixing appearances is a first step that will change the image of the neighbourhood and restore confidence.

'It looks nice but it does not offer dwellers much. People need infrastructure and jobs, not paint over their walls'

- Mona Harb, urban studies professor

“Art is a way of communicating. Before thinking about what is going on inside the houses we need to embellish them,” he says.

“Then we will consider electricity and such things. You can live without electricity. At night it gets dark, you sleep. But you can’t live in ugliness,” he says.

Disputed territories

But Nasser faces other challenges. “Ouzville” angered landowners because the area of Ouzai is at the centre of long-lasting and complex disputes over land property and illegal settlements.

During the Ottoman empire and the French mandate, the area was known as “the sand zone” as it consisted essentially of sand dunes.

It only started gaining strategic importance in the 1950s with the development of new residential zones and national infrastructure projects such as Beirut airport, a few kilometres south.

People started coming to the area to work on the construction sites. They settled and built their houses in what is now Ouzai, but without buying the land.

During the civil war (1975-1990), things took a new turn with a massive influx of refugees from the south of Lebanon - mostly Shia Muslims - who settled illegally in Ouzai and nearby.

With time, the southern suburbs became known as a stronghold of Shia political parties such as Hezbollah and Amal.

Academic researcher Valerie Clerc-Huybrechts sums up the situation in her book Irregular Districts of Beirut, published in 2008: “The southwest suburbs [of Beirut have] developed on land that did not belong to those who built it and without the agreement of the owners.”

Landowners have tried to claim back their property many times but so far every legal attempt has failed, they say.

Fadia Yared owns parcel 255 in Ouzai. Her 3,000-square-metre plot of land is currently occupied by 11 families, who she says she is unable to expel despite decades of legal procedures.

When she heard about “Ouzville,” she was infuriated and immediately warned Nasser that if a drop of his paint touches her walls, she’d file a lawsuit against him for violation of private property and promotion of illegal settlements.

“With all the attention Ouzville is getting it will now be impossible for us to expel the squatters,” she says, as she flicks through the pages of her legal file.

'With all the attention Ouzville is getting it will now be impossible for us to expel the squatters'

- Fadia Yared, local landowner

“I have nothing against embellishing the country, but while Nassar glorifies himself, while the public finds it amazing, nobody cares if our rights are being spoiled. This is not a no-man’s land.

“He is promoting an illegal situation; people have to be aware of this. Even tourists have to know that Lebanon is not just about fun and parties - there are real issues here,” she adds.

By the end of the summer, Yared hopes she can gather other landowners around her to open a collective legal procedure against Nasser and Ouzai’s illegal settlers.

For Nasser, making a place pretty is not a crime. “She can tell me exactly where her land is, we will leave it grey and ugly.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].