The Rohingya: Has the UN failed Myanmar's Muslims?

A fortnight before Cyclone Mora slammed into his home, Abdel drank tea with us on his porch, reflecting bitterly on his surroundings.

"It is a prison," he said, his eyes surveying the makeshift neighbourhood that he has been forced to live in for five years.

Abdel, a fortysomething whose name has been changed to protect his identity, is a member of the long-persecuted Rohingya minority, a largely stateless Muslim group based in Myanmar's western Rakhine state.

He is one of tens of thousands living in crowded, insanitary camps for the displaced in the region. The Thet Kyae Pyin camp is less than 10 miles from Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine state and Abdel’s former home. His family were driven out by Buddhist mobs during widespread violence five years ago. Abdel used to own two fishing boats and a furniture-making business. They have gone; what became of them, he does not know.

Now he carves out a bare existence in a camp surrounded on three sides by military and police checkpoints and a dusty wicker fence. On the fourth side is the sea. Occasionally a fisherman takes to the water and sells his catch to the residents.

Abdel gesticulated around the settlement. "They are trying to make us beggars," he said of the ethnic nationalists, who forced him and other Muslims from their own neighbourhoods. "They want us to be beggars in our new home and beggars to the international community."

Around us there was bustle, despite the heat and humidity. Children played. Women gathered in colourful hijabs. When aid workers first built this part of the camp it was just a cluster of tents. While we spoke to Abdel, the sound of hammering filled the air, as the men sought to improve their makeshift homes, resigned to the fact that no one will be leaving the refugee sprawl any time soon.

Abdel has extended his own family home, although it was still little more than a hut. It consisted of two rooms, each around three metres square; one for cooking and living, the other for sleeping for himself, his wife and three children.

There was also the stench of sewage. The camp is situated on a low water table. The latrines - one of which was close to where we sat – are mounted on brick supports. “The sanitation here is terrible,” Abdel complained, glancing across the dirt road nearby.

He was aware that he was laying down roots in an open-air prison which he longs to leave while also trying to make the best of it. Inside the hut he had pinned English alphabet posters; the type wouldn't look out of place in a primary school.

Children gathered around as we spoke. A neighbour brought over a pack of biscuits, stamped with the acronym “WFP”- the World Food Programme.

Abdel explained that access to the camps for UN workers was rare, even since the recent outbreak of violence. "The United Nations are not doing enough," he said. "They are putting some pressure but not strongly enough and not specifically enough.

"If the United Nations spoke out, if they tried to get inside here and help us - maybe the monks wouldn't do what they do."

Why Abdel, and thousands more Muslims, fled

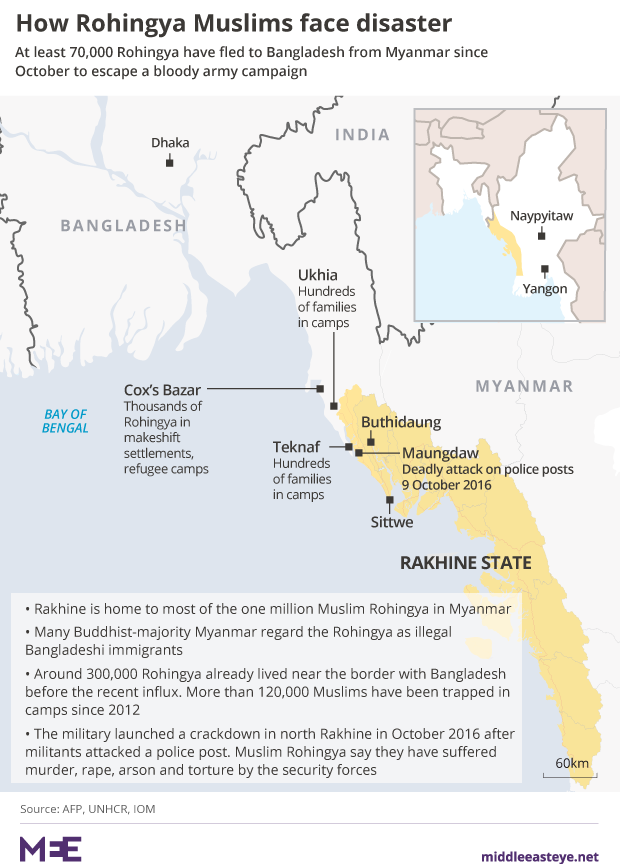

An estimated 120,000 Muslims now live in dozens of de facto internment camps across Rakhine state under conditions similar to Abdel. They are unable to leave the settlements, in which they are largely reliant on humanitarian assistance to survive. Their human rights, including freedom of movement, are far from settled.

There have long been tensions in the region between the Muslim Rohingya and the predominantly Buddhist ethnic Rakhine, yet trade and friendships persisted.

But then, in 2012, the rape and murder of a Buddhist woman sparked the first waves of large-scale violence in decades directed at the Rohingya, sparking a protracted crisis which saw Muslims confined to their camps. Human Rights Watch accused Myanmar’s state agencies, including the police and military, of participating in violence that amounted to “ethnic cleansing” and “crimes against humanity.”

In 2012, Sittwe was about 40 percent Muslim; now the proportion is less than three percent

At that time Sittwe was about 40 percent Muslim; now the proportion is less than three percent. At least 70,000 Muslims were driven from their homes in Sittwe Township alone. Mosques were burned but still stand, blackened and empty, in the centre of the city, not far from where Abdel used to live.

In October 2016, a Rohingya militant group attacked border guards, claiming that they had taken up arms to fight for the human rights they have long been denied. It is estimated that the Myanmar army may have killed more than a thousand Rohingya men, women and children in the crackdown that followed.

More recently, a report issued by the World Food Programme on 5 July warned that tens of thousands of children face acute malnutrition in the coming year.

It said that an estimated 80,500 children under the age of five are malnourished, based on an assessment of 45 villages in western Rakhine state.

Abdel lays a precious hand-drawn map out on a table. It shows the region, with neatly written figures besides the name of each town and village. The document details the number of deaths, the number of houses razed, the number of injuries during the purges. The scale of the “cleansing” that the Rohingya have faced is horrific.

“Before I had hope,” Abdel said, “but now I am hopeless. Now we don’t even have a parliament member to represent us. We can’t even vote.”

The estimated one million Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar were stripped of their right to vote ahead of the 2015 elections. The National League for Democracy party, which won a landslide, did not field a single Muslim candidate due to pressure from anti-Muslim Buddhist nationalists.

The party’s best-known member is Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, the de facto head of government, who in April 2017 denied that the Rohingya are victims of ethnic cleansing. She also opposes a UN fact-finding mission mandated by the UN Human Rights Council to investigate allegations of atrocities. Instead the Muslim Rohingya have had to look for support beyond Myanmar.

Abdel said: “We have nobody to represent us here. My trust is only in the international countries.”

But the efforts made by international organisations, especially the United Nations, appear to have raised more issues than they have solved.

An MEE investigation has revealed that sources within the UN, humanitarian community and international rights organisations are critical of how the Rohingya crisis has been handled by senior UN officials and, more broadly, by the organisation’s diplomatic presence in Myanmar.

Many of those who spoke to MEE did so on condition of anonymity, lest they face retaliation which might affect their careers.

Criticism #1: The UN's leadership style

Renata Lok-Dessallien is the UN’s resident coordinator in Myanmar - the most senior official in the country.

Lok-Desallien was appointed in 2014 and immediately faced a crisis when reports emerged of an alleged massacre of Rohingya in Northern Rakhine state. The incident, and the UN’s handling of it, remains controversial.

Initial reports suggested that up to 40 people had been killed at the village of Du Chee Yar Tan, but subsequent enquiries suggested that these figures may have been overstated. The resident coordinator allegedly blamed the OHCHR, the UN’s human rights agency, for making a mistake on the issue, although email records seen by MEE indicate that she had endorsed the death toll.

Relations with the government of Myanmar were seriously damaged by the incident. Lok-Desallien had to scramble to improve ties after the authorities mounted a campaign of denial about the alleged massacre.

Lok-Dessallien has served in Myanmar before: between 2000 and 2002 she was the UN Development Agency’s deputy resident representative. Prior to her return to the country she served in China, Bangladesh and Bhutan as resident coordinator.

An experienced humanitarian source in Sittwe described Lok-Desallien as “weak on human rights and generally unsupportive of anything that would bring things up to minimum international standards” in the refugee camps.

“No one has been lobbying the government or donors about shelter,” he said, referring to countries that fund humanitarian programmes.

In June, a UN spokesman, quoted by the BBC, speculated that Lok-Dessallien was leaving her post and that the decision had nothing to do with her performance. But the diplomatic and aid community in Yangon said that the move was linked to her failure to prioritise human rights, the broadcaster also reported.

A report, published by the International Rescue Committee (IRC), said that "sub-standard shelter conditions" in Myanmar have had a "debilitating impact" on the "well-being of internally displaced people”.

It said that “progress has been painfully slow” on shelter repairs, that conditions could not continue as they were and that standards in the camps still fell below international standards as outlined by the Sphere project, five years after refugees first lost their homes.

'No one has been lobbying the government or donors about shelter'

- Humanitarian source, Sittwe

Sphere, which is funded by the US, Germany and Ireland among others, specifies that the minimum “covered floor area” per person should be 3.5 metres squared. But the IRC found that the area for those “living in longhouses in Sittwe IDP camps” was 2.9 metres squared. That figure does not reflect refugees living in tents, where conditions are often worse.

The report also noted that the poor state of shelter was contributing to “excess morbidities for preventable diseases such as dysentery, tuberculosis and scabies”.

A UN source told MEE that camp conditions were also responsible for worsening psycho-social problems – and even violence. “The longer people are kept in the camps, there is more gender-based violence, their mental health [deteriorates],” he said.

But Charles Petrie, resident coordinator in Myanmar between 2003 and 2007, said that problems with shelters were ultimately rooted in a lack of support from donors in governments.

"On the question of meeting the Sphere standards, I am not sure it is as much an issue of UN leadership - it's more a question of the availability of funds from donors. If you don't have that the standards are difficult to meet.”

Camp conditions dramatically worsened when Cyclone Mona damaged Rohingya shelters in Rakhine state and across the border in southern Bangladesh in May 2017. MEE was unable to reach Abdel after the cyclone has passed. Muhammad, another resident in the camp, said that many people had fallen ill due to the worsening conditions.

Criticism #2: In-fighting within the UN

Divisions within the UN are also complicating its efforts to improve the lives of vulnerable people in Myanmar, including the Rohingya, according to another document seen by MEE.

An internal note sent to UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres in April 2017 observes that the organisation in Myanmar has become “glaringly dysfunctional”.

“Strong tensions exist within the UN Country Team. The humanitarian parts of the UN system finds itself having to confront the hostility of the development arm, while the human rights pillar is seen as complicating both,” the document said.

The note also said that there “are potentially a number of parallels between the UN’s approach to dealing with the conflict in Sri Lanka and its efforts in Myanmar”.

Tens of thousands of civilians were killed in so-called “no-fire zones” by government forces during the final days of the civil war in Sri Lanka in 2009. A damning internal review found that there had been a “systemic failure” by the UN to uphold its responsibilities for protecting the vulnerable due to a system weakened by a “culture of trade-offs” with the government in Colombo.

The internal note about Myanmar said that UN decisions have been taken without consultation, noting that like in “Sri Lanka, actions are decided and decisions taken in a manner that do not seem to indicate comprehensive ownership or responsibility for their impact”.

A document, dated 19 February 2016 and signed by 11 aid agencies working in Rakhine state, also supported these observations. The letter, entitled “On Behalf of the INGOs Engaging in Humanitarian Action in Myanmar”, protested at the decision by the resident coordinator to unilaterally appoint a deputy humanitarian coordinator.

The new role was created in February 2016 to reduce the humanitarian responsibilities of the resident coordinator. It effectively deputised the job of handling relations with the humanitarian community to the person who would occupy the new position.

The note said that the signatories “express our concern about the non-consultative process, communication and actual appointment of the Dpt. HC”, which was imposed by decree rather than consensus.

The preferred candidate of the NGOs was Mark Cutts, head of OCHA, the UN’s humanitarian agency, in Myanmar. Instead the position was awarded to Dom Scalpelli, a former head of the World Food Programme in Myanmar, who is perceived as holding views which are compatible with the resident coordinator.

Humanitarian workers in Sittwe told Middle East Eye that the appointment was seen as an attempt to reduce the influence of organisations which had been critical of the coordinator.

One experienced aid worker told MEE that it was part of a wider trend of the affairs of Rakhine being controlled from the centre.

Another NGO source said the appointment was made because Lok-Dessallien "doesn't want NGOs involved in coordination. She sees us as troublemakers because we hold her to account.”

Criticism #3: Inadequate early-warning system

The emergence of a Rohingya militant movement in October 2016 caught many in the UN by surprise, various sources including senior officials told Middle East Eye.

Further attacks could precipitate another crackdown by the military, increasing the risk of further violence against the Rohingya.

In December 2013, then-UN secretary general Ban Ki Moon introduced Human Rights Up Front, a global initiative designed to improve the organisation’s response to human rights crises and prevent future atrocities.

It came after a damning internal review into UN conduct during the final stages of the Sri Lankan civil war called for a “cultural change” so UN staff would take “principled positions and act with moral courage”.

Yet several sources – including UN officials – told MEE that the UN mission in Myanmar had failed to properly implement the new policy, something corroborated by documents obtained in 2016 and verified by MEE.

Philippe Bolopion, Human Rights Watch’s deputy director for global advocacy, met senior UN officials in Myanmar in early 2017. He told Middle East Eye that not enough was being done to uphold the initiative

Bolopion said “there should be a coherent, system-wide approach and strategy” on Rohingya rights, but that such an approach “simply doesn't seem to be there".

He said that the UN system as a whole in Myanmar had not seized on the human rights catastrophe and that the response had been subdued.

“The UN are almost bystanders in the face of very serious abuses that they should be fully mobilised to combat,” he said.

Others agreed. An official working within the UN system said that “Human Rights Up Front is not on the agenda”.

Criticism #4: Lack of international action

But the problem is not just with the UN. MEE has seen a letter, signed by senior members of NGOs, which highlighted the need for concerted action to protect civilians across Myanmar, not only in Rakhine state but also in Kachin and Shan state.

It was circulated privately among embassies and senior UN officials during last year’s crisis, when Rohingya were being slaughtered and fleeing to Bangladesh.

The letter compared the response of the international community to the crisis – and toward operations taking part in the eastern part of Myanmar – to the final days of Sri Lanka’s civil war.

It said that there was a lack of any comprehensive strategy to tackle the crises in Myanmar and prepare for the risk of future escalations. It added that “like Sri Lanka, we are still disorganised as a community and we are underestimating what is possibly in front of us”.

Referring to the warning signs of the catastrophe in Sri Lanka, it added “we saw the signs early then, and we see the same signs unfolding before us now, only with greater clarity and foreboding".

The signatories stated that they “strongly believe that the only way to effectively avert a crisis of atrocity is through all levels of the international community working earnestly and in concert”.

One of the signatories was Charles Petrie, who chaired a panel commissioned by the UN to review its conduct of the Sri Lanka conflict.

“The Sri Lanka parallel works in terms of referring to the inability of the UN to approach the situation in Myanmar in a coherent way with responsibility taken at the highest level,” he told Middle East Eye.

“The UN continues to have a diffuse, uncoordinated approach to the problems in Rakhine.”

He said that the ultimate responsibility for this failure could not be laid at the feet of those working in Myanmar.

“The responsibility for a coordinated approach falls on New York. The [resident coordinator] does not have oversight of the political and human rights strategy; she's a cog in the machine. The definition of the RC role is to be the coordinator of the UN system’s development activities."

Criticism #5: Prioritising development over human rights

But where should the focus of solving the crisis be?

Some analysts and senior UN officials, both within and outside Myanmar, believe that the chief impetus to improve conditions for the Rohingya lies less with human rights advocacy and more with economic development.

Media reports indicate that the dominant approach of senior UN officials within Myanmar, including the resident coordinator, has been to avoid robustly challenging the government on its poor rights record. Instead it favours a “pragmatic” approach through which improvements can be gradually brought about for the Rohingya.

This approach was criticised in a review paper, authored in late 2015 by Liam Mahony of Fieldview Solutions, an external group which advises on strategic planning, research and analysis to international organisations in conflict zones.

The document, seen by MEE, was commissioned by the OHCHR. It examined the human rights implications of the UN’s approach to the Rakhine crisis.

The author noted that “excessive self-censorship” on rights was contributing to a situation in which “international institutions” were being forced “into complicity with systematic abuses” against the Rohingya.

The "current UN strategy of emphasising development investment as the solution to the problems in Rakhine state," the study further observed, "fails to take into account that development initiatives carried out by discriminatory state actors through discriminatory structures will likely have a discriminatory outcome.”

A cache of documents obtained by MEE demonstrate that not long after this document was written, the United Nations and some of the diplomatic community in Myanmar constructed plans to continue prioritising development - even as they were seeking to improve the rights of the Rohingya.

The papers were drawn up in October 2015, about a year before the current Rohingya insurgency began. They laid out a two-year plan up until 2017, involving a “Heads of Mission” group, drawn from Western embassies and parts of the United Nations.

One key document, entitled “A whole of Rakhine approach” envisioned tackling the “major human rights crisis” endured by the Rohingya, but only in phases.

The author, British consultant Lewis Sida, argued that in the final stage of the UN strategy the Rohingya would have finally attained their full human rights.

Then, and only by then, would key issues related to rights such as the Rohinya’s citizenship status be resolved. The document states this could be 15 years from the time of Suu Kyi’s election in 2015 – that is, 2030.

'Market-based solutions only get you so far. How many more people have to die before the UN leadership stops tip-toeing around Myanmar’s leaders?'

- Matthew Smith, Fortify Rights

A source in the international NGO community in Sittwe warned that “the whole donor community is invested” in the idea that development had to precede any significant changes for the Rohingya.

But human rights groups insisted that the severe rights deprivations suffered by the Rohingya, which are largely the product of widely supported legislation, need to be tackled urgently.

Matthew Smith of Fortify Rights, a non-profit human rights organisation based in south-east Asia, said: “The idea that development in stages will somehow end pogroms, end impunity, resolve fundamentally legal problems, is confused at best. Market-based solutions only get you so far. How many more people have to die before the UN leadership stops tip-toeing around Myanmar’s leaders?”

A UN source who spoke to Middle East Eye said that economic development would have to precede any end to the detention of Rohingya in camps.

“The camps are likely to stay in place until the economy improves,” he said. “And no one should be expected to leave until then.”

He indicated that the process could take at least another five years.

What the UN says about the Rohingya

Pablo Barrera, a media spokesman for the Office of the UN Resident Coordinator in Myanmar, told Middle East Eye that the questions resulting from the MEE investigation “reflect the opinion of partners and individuals".

Barrera said: “While I fully respect them and I recognise that they are driven by the very desire and determination to find solutions to the situation of the people in Rakhine state - a desire and determination which I can assure you is shared by all of us involved in this very complex operational environment - I would prefer not to further speculate on these questions as it may lead to an inward looking turf battle/gossip type of discussion, not necessarily helpful to the objective of improving the situation in Rakhine.”

He described the situation in Rakhine as “extremely complex” as demonstrated by the number of groups and agencies “which are relentlessly searching for viable and sustainable approaches to help Myanmar to make progress".

Barrera said the government of Myanmar was ultimately responsible for ensuring the protection and wellbeing of its people and the difficulties in Rakhine state.

“For decades, due to a combination of reasons, successive governments have neglected the undertaking of measures aimed at addressing the causes and ensuring a dignified life and the enjoyment of basic rights, often abdicating on other entities the task to provide assistance to the population.

“In this context,” Barrera said, “the UN together with the entire humanitarian community have advocated for the government to take up its primary responsibilities while providing the necessary assistance to cover the humanitarian needs of the population.

'The contribution from all development and humanitarian partners, including UN agencies NGOs, diplomatic missions, consultants and experts is very much sought and welcome'

- Pablo Barrera, Office of the UN Resident Coordinator in Myanmar

“While firmly advocating on the humanitarian principles and international human rights standards, the humanitarian partners are also striving to pursue a constructive engagement with the government to ensure the respect of these principles. These advocacy efforts were further escalated after the events on 9 October, 2016.”

The UN, Barrera said, is “committed to remain engaged in supporting solutions in Rakhine state to the benefit of all communities and individuals. The contribution from all development and humanitarian partners, including UN agencies, NGOs, diplomatic missions, consultants and experts, is very much sought and welcome. There is certainly a need to join forces of all diverse entities in order to support constructive approaches to improve the situation of the population in Rakhine state."

Where does all this leave Muslims?

If mass violence does return to Rakhine, it would most likely be perpetrated by the military in response to an act of Rohingya militancy.

“We are not terrorists,” declares Atta Ullah, the leader of the Rohingya insurgency, speaking into the camera in a video released last year, as fighting between the insurgents and Myanmar army raged. Beside him laid wounded comrades, displaying visible gunshot injuries. “We do not want anything except our rights.”

A press release from the group announced in March: “We were hoping that [the] international community would take necessary measures including sending peacekeeping forces... to protect Rohingya from being subject to genocide We demand... [our] rights.”

Abdel is determined to ensure that he, his family and friends do not take up arms.

Like the overwhelming majority of Muslims in these camps, they view themselves as victims and don’t believe their plight will improve if they use weapons.

Yet such restraint, while admirable, alters nothing: Muslims like Abdel must still endure life in the open-air prison to which he has grown accustomed, knowing full well that he is set to be immured in its confines for years to come, even as development money looks set to flow into the city where he once lived freely.

Whether the Rohingya men, women and children, herded into those camps, will ever benefit from that investment remains to be seen.

- Peter Oborne won best commentary/blogging in 2017 and was named freelancer of the year in 2016 at the Online Media Awards for articles he wrote for Middle East Eye. He also was British Press Awards Columnist of the Year 2013. He resigned as chief political columnist of the Daily Telegraph in 2015. His books include The Triumph of the Political Class, The Rise of Political Lying, and Why the West is Wrong about Nuclear Iran.

- Emanuel Stoakes is a journalist and researcher who specialises in human rights and conflict. He has produced work for Al Jazeera, The Guardian, The Independent, The Huffington Post, Foreign Policy, The New Statesman and Vice among many others.

- Alastair Sloan focuses on injustice and oppression in the West, Russia and the Middle East. He contributes regularly to The Guardian, Al Jazeera and Middle East Eye. Follow Alastair's work at www.unequalmeasures.com

- Abla Klaa is a video journalist and documentary producer with a special interest in Syria and the refugee crisis.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Rohingya refugee from Myanmar's Rakhine state holds a baby after arriving at a refugee camp near the Bagladeshi town of Teknaf on 5 September, 2017 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].