The Dragon and the Lion: China's growing ties with Syria

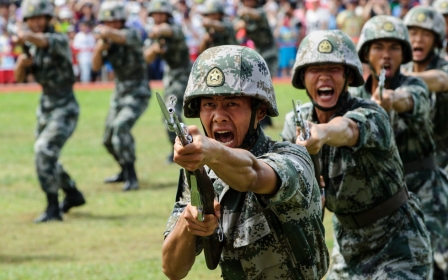

Last March, China quietly deployed troops to Syria. The soldiers, according to Chinese officials, trained members of the Syrian army, offering advice on medicine and logistics. Despite how little fanfare surrounded this move, it was, in fact, very significant: this is the first time China has sent troops to the Middle East for any reason other than to protect ongoing commercial projects.

The war in Syria has had a significant impact on global stability with grave implications for European security, the American presidential elections of 2016 and for Islamist non-state groups operating in Asian countries such as China, Philippines, Malaysia and even the secure city state of Singapore.

The effect of the war on China’s policy in the Middle East since 2014, particularly in Syria, has transformed it from one of caution to one of proaction.

While Beijing’s engagement was initially motivated by security concerns - including fears of Chinese nationals fighting in Syria and returning east - over the past two years, the blossoming relationship has seen both China’s economic interests in Syria and the country’s hold in the Levant more broadly flourish.

Conflict resolution

As the Syrian conflict evolves on a daily basis, the stakes for East Asia’s security are high. With recent events such as the arrest in March of Islamic State (IS) operatives in Malaysia and in June in Singapore, and the links between Islamic separatist fighters in Philippines and Myanmar and groups operating out of Syria, the war can no longer be seen as detached from potential unrest in East Asia.

One major motivation behind Beijing’s mediation activity in Syria are an estimated 5000 Uighurs thought to be fighting in the war

Consequently, China has, for the first time on the global stage, encouraged conflict resolution as a third-party participant, taking a lead in talking to all sides in Syria. This month, the Chinese special envoy to Syria, Xie Xiaoyan, made a trip to Damascus, Beirut and Amman to further consolidate China’s efforts in seeking to resolve the conflict in Syria.

His visit follows China’s appointment of its first ever envoy to a Middle Eastern conflict zone last March and, since then, he has been actively engaged in the UN-led Syrian peace process in Geneva and the Astana peace talks. After South Sudan, where Beijing had a battalion as part of a UN peacekeeping mission, this was the first time China has appointed an envoy to a war zone and taken a forward role in a far-flung civil war.

One major motivation behind Beijing’s mediation activity in Syria are an estimated 5,000 Uighurs thought to be fighting in the war. One of 55 recognised ethnic minorities in China, the Uighurs are Turkic-speaking, mostly Sunni Muslims, living in the country’s northwest Xinjiang province – which has has had intermittent autonomy over the past few centuries – who view Beijing as a coloniser.

Beijing, on the other hand, sees the Uighurs and the Xinjiang province as the focus of what it fears could be a successful insurgency against the regime. In recent years, Uighurs have been linked to global militant movements, including al-Qaeda.

Historically, Turkey had been a supporter of the pan-Turkic movement – which aims to bring together all Turkic people across much of Central Asia, including the Uighurs – and served as a spiritual home for Chinese Muslim dissidents including the Uighurs.

Uighurs and East Asian tensions

With Uighurs increasingly joining militant movements, China and other East Asian countries have moved to try to halt this activity.

In July 2015, Turkish-Chinese ties hit an all-time low. Chinese tourists were openly attacked over a Turkish government-led campaign to criticise China’s repressive policies toward the Uighurs. China in turn accused Turkish diplomats of providing fake passports to Uighurs who they said would only go on to become “cannon fodder” for militant groups in Iraq and Syria. Then, this May, three Turkish citizens were arrested in Malaysia, suspected of funding the Islamic State.

Tensions between Turkey and China opened up an opportunity for the Syrian government to exploit a gap in Chinese intelligence agencies chasing Uighur fighters going to Syria. Southern Turkey has reportedly become a staging ground for Uighur fighters going to fight in Syria.

This undoubtedly led to China to send 300 military advisers to Damascus in April 2016 with the stated aim of providing medical and engineering training for the Syrian military. Over the course of last year, the Syrian military also hosted several Chinese military delegations as China stepped up its aid to Syria.

In August 2016, a high-level Chinese naval officer visited Damascus to sign memorandums of understanding, and work out a joint mechanism to fight terrorism and track not just Chinese militants but also other East Asians in Syrian prisons.

During this period, the governments of Myanmar and the Philippines – which allege that their own citizens have either fought in Syria or shown interest in joining groups there - have also pulled closer to China as they compare their own insurgencies to the ones in Syria. Certainly, in the past there has been evidence that al-Qaeda in Afghanistan was active in the Philippines and Myanmar, and sought to sow discord between often disenfranchised Muslims in East Asia and their Chinese co-citizens.

Malaysia has also suffered from the same problem and has a high level diplomatic presence in Damascus as a result of this to cooperate with the Syrian intelligence services. However, most of the smaller Asian countries like Myanmar and the Philippines have very little security presence in Damascus. When the war in Syria began, most Asian countries shut down their embassies with the exception of China, Indonesia and Malaysia. The Philippines had a consulate open because of the large number of domestic workers which are still to this day working in Syrian homes.

So now these countries are increasingly relying on China to help resolve the gaps in their own security relationships with Syria, and monitor the links between the war and their own militancy problems at home.

Reconstruction efforts

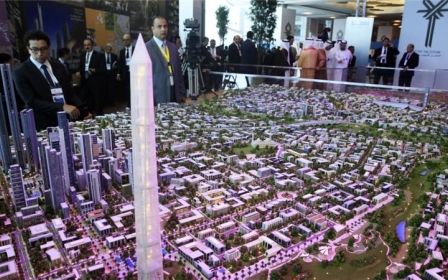

Another dimension of the Chinese ascendancy in Syria has been economic. With the war in Syria apparently reaching its final stages and the Syrian government now in control of 11 out of 14 provincial capitals, there has been an active push for reconstruction efforts in cities like Homs, Hama and Aleppo.

While Russia and Iran seem the obvious candidates to rebuild, both countries have economic problems of their own and it remains to be seen whether they could impact the Syrian economy and benefit from trade deals other than defence contracts. Since 2016, both India and China have thrown their hat in the ring for economic projects, sending several high-level business delegations and taking part in trade expos not just in Damascus but also in the coastal cities of Latakia and Tartous.

China’s rise in Syria is significant; it is one of the first truly global conflicts where the Chinese have carried out political, defence and economic diplomacy

Chinese economic interests in Syria date back to 2004 with the linking up of key strategic areas around Syria and Lebanon to its One Belt and One Road project (OBOR). This March, President Bashar al-Assad gave a high-profile interview to a Chinese media company in which he confirmed the visiting trade delegations and expanding academic links to China. China has also backed the Syrian government, voting and lobbying on behalf of the country at the UN at all the various forums and workshops.

Syria has benefitted immensely from a continued increase of Chinese interest in Damascus. An all-encompassing relationship between Damascus and Beijing which focuses on security, economics and geopolitics has slowly put China in an interesting position in the Levant. For China, there has been a very measured increase in their presence and relations with Damascus while it still sits on the sidelines of the actual conflict.

Soft-soaping Assad

On the softer side, Assad has been portrayed in the Chinese media as a liberal who believes in the potential of China in the Middle East, something affirmed by a Chinese presenter asking him soft questions such as why his son is learning Chinese. The Chinese business delegations have also been very proactive in seeking out Syrian government tenders and areas not just of reconstruction, but also bilateral trade deals.

Chinese diplomats in Damascus are quietly but determinedly eyeing up key areas of investment that can be linked to regional gains beyond Syria

Fundamentally, China has an ideological cohesion with the Syrian Arab Republic given its secular nature and disdain for anything that can be a cult either driven by religious identity or social movements based on populism. Cultural elements like educational exchanges between Chinese and Syrian universities, for example, have also been put at the top of the agenda of deepening Damascus-Beijing ties.

Damascus has shored up Chinese support in its war against terrorism. It has done this slowly through working with the Chinese on linking the One Belt One Road to the Levant and also exploiting the intelligence-sharing gap left wide open by the Turks.

The Chinese still see Damascus and the Syrian government as key to economic prosperity in the region, and even the Lebanese realise this and want to cash in on their closeness to Syria. Chinese diplomats in Damascus are quite forthcoming in their views about the security threat, while on the economic front are quietly but determinedly eyeing up key areas of investment that can be linked to regional gains beyond Syria.

China’s rise in Syria is significant; it is one of the first truly global conflicts where the Chinese have carried out political, defence and economic diplomacy. Furthermore they have made it clear to the other stakeholders such as Russia and the United States that the Syrian Arab Republic and the state are legitimate, and its territory must not be split. China has benefitted from the bickering between Russia, United States and Turkey.

In Syria, China has not just simply watched the Russian and US tug of war, it has cultivated its own path by avoiding military confrontation, instead focusing on consolidation and quiet, behind-the-scenes action.

- Kamal Alam is a Visiting Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). He specialises in contemporary military history of the Arab world and Pakistan, he is a Fellow for Syrian Affairs at The Institute for Statecraft, and is a visiting lecturer at several military staff colleges across the Middle East, Pakistan and the UK.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Image: In a handout picture provided by the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) shows Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (R) speaking with a journalist from China's Phoenix television on 22 November 2015, in Damascus. (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].