Football: Second religion of the Middle East

The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer is one of the weightiest, most revelatory, original and important books written about sport. Through it the author, James Dorsey, provides a thorough and unflinching examination of how football has impacted political, social and religious control in the Middle East and North Africa.

Dorsey presents football as a complex cultural tool that can enforce repression yet equally be a means of challenging authority.

He brilliantly exemplifies the game’s application as a tyrannical device by focusing on the improbable story of Al Saadi Qaddafi, the son of Libya’s longtime ruler.

Al Saadi owned, managed and captained popular club Al Ahly Tripoli, while also acting as head of the Libyan Football Federation. He allegedly murdered a national player and coach who criticised his influence, engineered rival club Al Ahly Benghazi’s relegation from the top flight of Libyan football and razed its stadium to the ground when fans protested against him.

Yet, by juxtaposing Al Saadi’s actions with instances where the game has served to disrupt structures of authority, Dorsey dissuades readers from drawing simple conclusions.

He positions the founding of Cairo team Al Ahly SC in 1907 as a response to sports clubs set up by the British occupying forces which excluded locals, illustrating how the club quickly became a “anti-colonial, anti-monarchist, nationalist rallying point”.

Similarly, he shows that the decision of 10 Algerian players to abscond from France in 1958 - and embark upon a world tour to promote the National Liberation Front (FLN) - gave Algeria’s independence drive considerable momentum. Ultimately, football emerges as a chaotic force, a (largely) metaphorical warzone in a region blighted by genuine conflict.

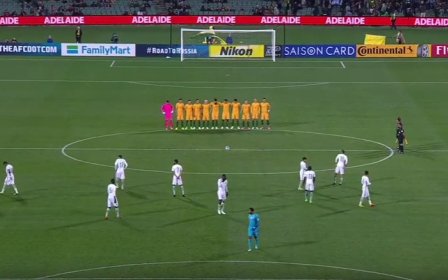

Accordingly, the stadium becomes a crucial space for Dorsey; a battleground for control between rulers looking to enforce order and fans who want to bring about change.

All too often stadiums are used as theatres of terror; sites where oppressive regimes carry out demonstrative punishments to promote a culture of fear

In Iraq, Uday Hussein would humiliate the national team in Baghdad’s Stadium of the People if they failed to qualify for the World Cup, an action reflective of the relationship between success on the pitch and political control.

Under the Taliban, stadiums in Afghanistan were routinely used to carry out ritual punishments, burn contraband materials and murder dissidents.

Yet, while Afghans still fear entering Kabul’s Ghazi Stadium after dark, Dorsey reminds the reader that, in other states, the football ground is central in the fight to transform oppressive regimes into more open, democratic societies.

Indeed, in much of the region, it has become the only public space which exists outside the sphere of autocracy. Dorsey draws parallels between the stadium and the university campus - long a breeding ground for revolution - presenting the former as an ideal “incubator for protest”.

As he notes, not only does its layout simplify the dissemination of ideas, it also offers protesters “strength in numbers” and, in cases where games are being broadcast live, threatens to publicly expose the regime’s repression.

At the heart of Dorsey’s study is the fascinating story of the Egyptian Ultras, the fanatical supporters who played such a crucial role in the Tahrir Square protests in 2011 which toppled then-Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak. By illustrating how these fans - through extended clashes with security forces inside stadiums - were pivotal in breaking the cycle of fear that had enveloped society, he provides readers with a startling perspective through which the Arab Spring can be explored.

The Ultras showed that “the security forces were not invincible”, and in doing so, opened the door for change. Moreover, these stadium clashes were vital when it came to the protests themselves. The Ultras’ experience “forced them to develop skills that were alien to the middle class”. Without their militancy and organisation, the toppling of Mubarak may have proved impossible.

By mapping the assimilation of the word “Ultra" into other spheres of Egyptian society, Dorsey demonstrates the monumental impact of the group. Ultras Nahdawi, for example, are militant fans tied to the Muslim Brotherhood and Morsi, rather than any specific football club.

Contradictions between football and Islam

The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer also allows Dorsey to investigate the complicated relationship between football and Islam. Here, he unearths another striking paradox: that although many Islamists have long disapproved of the game, it has often been used as a lure to radicalise Muslim youth.

Conservative clerics have denounced football on the grounds that it is un-Islamic, that it distracts from Western evils, and that its rules challenge the supremacy of Islamic law. Former grand mufti of Saudi Arabia, Muhammad Ibn Ibrahim al-Sheikh cautioned that football can lead to "the emergence of hate and malice", claiming that the game contravenes the Islamic notions of "tolerance, brotherhood, rectification and purification of hearts".

Osama Bin Laden developed a deep love affair with the game: as a child he would organise matches in Jeddah, using them as a 'platform to preach his conservative views of Islam'

When Al-Shabaab controlled large swathes of Somalia, watching the World Cup was outlawed altogether. Homes were raided, and those caught watching the game flogged or executed. Yet, “Al-Shabaab mentor” Osama bin Laden developed a deep love affair with the game: notoriously a fan of Arsenal FC, as a child he would organise matches in Jeddah, using them as a “platform to preach his conservative views of Islam”.

Furthermore, a childhood friend of Bin Laden recalls how they were encouraged to attend extra-curricular Quran classes with the promise of football. The games were always badly organised, while the sermons became increasingly violent. And Dorsey illustrates that just as stadiums can be an ideal “incubator for protest” so football teams can act as an incubator for jihad.

In many cases, a background in the game “encouraged camaraderie and reinforced militancy”; recruiting from football teams also enables the creation of “strong and cohesive jihadist groups’; tight-knit cells that communicate face-to-face and are difficult to break down.

Dorsey rightly concludes that the condemnation of football is primarily due to its “potential threat to political and social control” rather than any moralistic concerns. Throughout, he demonstrates that football is a complex instrument, one that becomes threatening to authority structures when it transcends their control.

How football affects fabric of society

The book also explores the game’s impact as an identity shaper within the Middle East and North Africa, illustrating at length how football can provide women with the opportunity to defy regimes that often demote them to the status of second-class citizens.

After Iran qualified for the 1998 World Cup, “celebrations turned into a demonstrative rejection of Iran’s strict restrictions on mixing of genders, women’s public appearance and the consumption of alcohol”.

And in 2012, two Iranian women disguised themselves as men to gain entry to the World Cup qualifier against South Korea, publicly revealing their identity after the game. Both incidents illustrate that football opens the door to “feminine defiance”.

Likewise, by encouraging FIFA to impose sanctions on nations without women’s teams, Egyptian Sahar al-Hawari – the "outspoken daughter of an international soccer referee" - forced Arab nations to reform. The women’s game has been a source of much controversy, but Dorsey adeptly illustrates that the backlash is as much due to conservatism as religiosity.

Dorsey demonstrates that football can prove vital in the establishment of national identity. In the case of Palestine, FIFA’s recognition has legitimised “national aspirations”; in post-Saddam Iraq, triumph in the 2007 Asian Cup briefly united a nation on the brink of civil war. An Iraqi education ministry employee is quoted as saying that “[n]one of our politicians could bring us under this flag like our national football team did”. Dorsey repeatedly proves that football truly can generate change within society.

If any criticism can be levelled at The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer, then it is that the focus is so broad, that football’s impact within the region is so far reaching and seemingly contradictory. As a result, Dorsey is unable to consolidate his findings into a singular, clear narrative.

In particular, the final chapter - where Dorsey explores the Gulf states’ drive for initiation into the global soccer elite - feels somewhat separate from the rest of the study, almost like the starting point of another book.

Yet this is a remarkable work, the result of meticulous research, through which Dorsey establishes football as a formidable cultural institute, a game that can arouse deep-seated passions, that can and will continue to disrupt authority structures.

It deserves to be seen as a classic and inspire many similar studies, establishing football as a hugely important practice within the region in the 21st century, perhaps only second to Islam itself

Along the way, he rewards readers with a wealth of extraordinary stories: we learn that players in Libya were referred to only by number to prevent them from becoming too popular; that long-time Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser would regularly discuss Al Ahly results in cabinet meetings, despite having no real interest in the game; and that studies in Egypt have established a clear link between divorce rates and football fandom.

While The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer has received praise from the likes of Change FIFA, it has been relatively neglected since its publication last year. Perhaps this is because this pioneering volume covers so much ground that it seems to oscillate between a number of separate categories. The chapters are distinct, yet feel as if they could exist as separate essays in their own right.

But it deserves to be seen as a classic and inspire many similar studies, establishing football as a hugely important practice within the region in the 21st century, perhaps only second to Islam itself.

The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer, by James M Dorsey is published by Hurst & Company, London.

- Peter Oborne was named freelancer of the year 2016 by the Online Media Awards for an article he wrote for Middle East Eye. He was British Press Awards Columnist of the Year 2013. He resigned as chief political columnist of the Daily Telegraph in 2015. His books include The Triumph of the Political Class, The Rise of Political Lying, and Why the West is Wrong about Nuclear Iran.

- Nicholas Brookes is an independent writer and journalist from London. He has contributed to a number of publications in the UK and is currently working on his first book.

The views expressed in this article belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A masked Egyptian protester is seen during clashes with riot police near the interior ministry in the capital Cairo on February 6, 2012, as one protester was killed in the wake of deadly football violence and amid calls by activists for civil disobedience in Egypt (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].