Qatar should seize the day and end the Gulf crisis

After nearly three months of the worst diplomatic crisis between Qatar and Saudi-led countries, the first sign of a thaw appeared on the horizon earlier this month when King Salman of Saudi Arabia ordered the reopening of the kingdom’s border with Qatar to facilitate the annual Hajj pilgrimage.

The decision came after Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman received an envoy from Doha, according to the official Saudi Press Agency.

Qatar should consider what started the crisis in the first place so it can prevent further feuding and keep hold of its pride and sovereignty

The Saudi initiative is the first clear attempt, even if it is just a face-saving one, to ease the tension between the two GCC countries, given the damage that the crisis has inflicted on both sides.

Now that Saudi has made its Hajj concession, it’s unlikely the blockading countries will offer anything more, so it is Qatar’s turn to defuse the crisis.

Doha should provide good-intention guarantees, including de-escalating the anti-Saudi campaigns by its broadcaster, Al-Jazeera, and washing its hands from sponsoring Islamist groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood, and especially any individuals or groups listed in the Saudi demands who preach for violence or have been sentenced in absentia.

More broadly to calm tensions, Qatar should consider what started the crisis in the first place so it can prevent further feuding and keep hold of its pride and sovereignty.

Root causes of the crisis

Both sides of the conflict have mishandled their differences over various issues since June. But the real bone of contention between the two is how they have approached the political turmoil in the region following the Arab uprisings.

While Saudi Arabia has focused on maintaining stability over democratic change, Qatar claims to support movements – including Islamist groups who have the most organised forces - pushing for this change.

Qatar’s approach has led to the kind of instability that countries now boycotting Doha fear the most, one which has left power vacuums which they worry that rival countries, like Iran, and movements will fill.

So the current geopolitical landscape in the region would appear to swing the pendulum towards the advocates of stability and the pre-Arab uprising era.

Signs of a thaw

The first glimmers of hope for reconciliation came after diplomats from countries involved in the blockade – the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Egypt - realised that their original 13 demands were unrealistic.

On 18 July at a UN press conference, they announced that they were replacing the demands with six broad principles related to counter-terrorism, first revealed at a 5 July meeting of the countries’ foreign ministers in Cairo.

The six principles give Qatar the space it needs to save face and determine its own approach in order to abide by the classified agreement made among the GCC countries in November 2013.

Leaked to CNN and released in July, that agreement includes ending any alleged funding and support for Islamist groups in the region.

What Qatar should do

Qatari geopolitical interests should be aligned with Saudi Arabia and the rest of the GCC countries. Maintaining distance from Iran and Hezbollah is strategically vital for the unity of the GCC countries.

Iran has expansionist aspirations in the region which have fuelled the flames of ongoing civil war in Syria and Yemen, through Tehran’s support of the Houthis.

Since Donald Trump’s election, the US, which is a major ally to Gulf countries, has taken a hard tack with the Islamic republic, leaving the future of the 2015 nuclear deal at stake.

In other words, Iran is a losing card.

Despite the fact that the demand to shut down the Al-Jazeera network is no longer on the table, the Qatari government should ensure that its widely viewed media outlet is less biased and not drawn into the Islamist or Qatari foreign policy agendas.

Similarly, Saudi, Egyptian and Emirati media should also respond by scaling down their anti-Qatari campaigns and baseless claims against critical views.

More generally in the region, media should be as unbiased and professional as possible by abiding by its code of ethics and should not be a tool in the hands of governments.

For years, Qatar’s policies have clashed with those of other GCC states. The psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud had a term for this: "narcissism of small difference" – or when neighbouring communities with many commonalities fight over their differences.

Doha shares its only land border with Saudi Arabia, which given its leverage in the region and the size of its population, will never allow a relatively tiny, historically new country like Qatar to act as a counterweight to its de-facto decades-long hegemony.

Instead of insisting on emphasising their differences, couldn’t Qatar shift to make the relationship a win-win?

Diplomatic whiplash

While Trump’s pragmatic visit to Riyadh in May, the first visit to an overseas country, wasn’t the trigger of the crisis, it deepened pre-existing tensions between the two sides and brought their feud to a new level. Now the US may be the key to unlocking the peace – but not through the president.

Given his completion of an arms deal worth $110bn with the monarchy, not to mention the Egyptian president’s “ego-appealing“ comments during the summit that Trump is “capable of the impossible”, Trump’s alignment with the Saudi-led blockade against Qatar makes some sense.

“So good to see the Saudi Arabia visit with the King and 50 countries already paying off. They said they would take a hard line on funding extremism, and all reference was pointing to Qatar. Perhaps this will be the beginning of the end to the horror of terrorism!” he tweeted on 6 June.

Three days later, he told reporters at the White House: “The nation of Qatar, unfortunately, has historically been a funder of terrorism at a very high level.”

To “reinvigorate the spirit of the Riyadh agreement”, as Tillerson put it, he visited Doha on 11 July to sign a memorandum of understanding which was aimed at better tracking the financing of terrorism.

Qatari Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani denied any relationship between the memorandum and the ongoing Gulf crisis, saying that it had been in the works for several months, but this was likely to save face.

After his visit to Doha, Tillerson went on to Saudi Arabia to show that Washington was indeed pushing Qatar to be serious in its commitment with regards to the Riyadh agreement.

This de-escalatory step, however, has not yet translated on the ground into action by Doha, but might later have pressed the blockaders to scale back in their demands a week later.

Natural mediator

America has a strategic stake in maintaining alliances with both Qatar and with the blockading countries – including lucrative arms deals with both - which make it a natural mediator for the situation.

While Trump’s one-sided approach has been a stumbling block to all mediation efforts, Tillerson’s role as negotiator would be a win-win for all the parties involved.

The longer the crisis lasts, the more Iran, Turkey and Islamist groups in the region benefit from it. Therefore, Tillerson ought to continue his mediation mission while Trump’s advisers should convince him to stop tweeting, at least until a de-facto de-escalation is reached.

For its part, it is a high time for Qatar to make a face-saving concession to calm its neighbours’ concerns and fears about its sponsorship of certain Islamist groups who in reality have no power any longer.

Given Iran’s expansionist role in the region, Qatar should dissociate itself from Iranian attempts to build a regional alliance to counter balance the Saudi Arabia-led one; otherwise tensions will escalate beyond the point of return.

- Muhammad Mansour is an Egyptian journalist, who covered the Arab uprisings, and writes about Egyptian affairs, the Sinai insurgency and broader Middle Eastern issues. For more details, visit www.muhammadmansour.com.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye

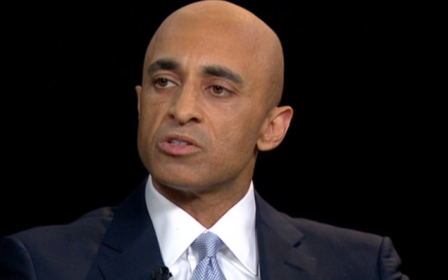

Photo: This August, an exhibition of artwork in the garden of the Islamic Museum in Doha depicting Qatari Emir Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani titled "Glorious Tamim: in celebration of national unity" (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].