Anti-violence law is another victory for Tunisian women

On 26 July 2017, the Tunisian parliament passed a law on the "Elimination of Violence Against Women," a broad piece of legislation which promises to dramatically impact the state’s handling of gender-based violence, the prosecution of abusers, and the protection of survivors.

Hailed as a "landmark step" in Tunisia’s efforts to combat violence against women, the law defines new criminal offences, significantly modifies current legislation and mandates several new government initiatives.

Following the announcement of the final vote, celebratory cries and a spontaneous rendition of the Tunisian national anthem broke out in parliament.

Opponents accused foreign forces of using the law to declare war on Islam and separate Tunisia from its Islamic heritage

But the unanimous vote belies years of arduous effort that ultimately led to its enactment. After the Tunisian transitional government announced in 2014 that it was drafting a law to combat violence against women, the initial legislation encountered significant resistance, particularly from conservative politicians and media outlets.

Opponents accused foreign forces of using the law to declare war on Islam and separate Tunisia from its Islamic heritage.

In response, Tunisian civil society and feminist groups started advocacy and awareness-raising missions at home and overseas, and campaigned in the media to highlight the prevalence of violence against women in Tunisia.

The final bill is the product of years of debates, compromises and substantial revisions. Given that studies in recent years have revealed alarming levels of violence against women across the country, the law marks a sorely needed step forward.

Dangerous legal ambiguities

In 2014, Tunisia ratified a new constitution widely considered the most progressive in the Arab world. But while the constitution committed generally to “protect women’s accrued rights and work to strengthen and develop those rights,” its enshrined principles did not immediately translate into legislative action.

Before the passage of the new legislation in June, no law specifically addressing violence against women existed in Tunisia. Though violence against women could be prosecuted under the Tunisian Penal Code, the relevant laws were poorly suited to the specificities of gender-based violence.

Given that many women face significant social pressure to withdraw their complaints or are financially dependent on abusive husbands, the withdrawal provision was particularly problematic: between 2010 and 2011, 72.5 percent of the 5,116 complaints filed were either withdrawn or dismissed.

Rape laws are similarly flawed. Although the Tunisian government claimed that marital rape fell under the broad language of Article 227 of the penal code, no law specifically criminalised spousal rape or intimate partner violence.

The penal code included a troubling loophole allowing rapists to escape punishment if they married their victim

Moreover, the penal code included a troubling loophole allowing rapists to escape punishment if they married their victim. In 2016, a district court in the Tunisian city of Le Kef made headlines when it dropped all charges against an alleged 20-year-old rapist who married his 13-year-old victim. Although the decision was later overruled by an appeals court, the announcement provoked large-scale national protests.

But troubling legal provisions in regards to violence against women go beyond the penal code. Article 23 of the Personal Status Code required spouses to “fulfill their conjugal duties according to practice and customs,” a provision which is, as Amnesty International pointed out, was “generally understood to mean that sexual relations constitute a marital obligation.”

A 2010 study conducted by the National Family and Population Office found that 20 percent of women had experienced physical violence committed by their partner. Given the prevalence of intimate partner violence in Tunisia, the legal ambiguities around violence against women compounded a particularly dangerous situation.

Steps forward

The hope then is that the new legislation could serve as a cornerstone in the state’s constitutionally mandated efforts to end violence against women.

The law provides a clear definition of domestic violence in accordance with UN recommendations, and addresses acts resulting in “psychological or economic suffering". It's a notable departure from the Tunisian Penal Code which “addressed physical violence only” and does not include “economic and psychological violence”.

The law provides a clear definition of domestic violence in accordance with UN recommendations, and addresses acts resulting in 'psychological or economic suffering'

The law additionally eliminates the “loophole” which allows rapists to escape punishment through marriage, raises the age of consent to 16, creates new criminal offences for violence committed "within the family," and establishes criminal liability for judicial actors who attempt to "coerce" women to withdraw their complaints.

Furthermore, as Human Rights Watch noted, the law “criminalises sexual harassment in public spaces, and the employment of children as domestic workers, and fines employers who intentionally discriminate against women in pay”.

Beyond expanded criminal liability for perpetrators, the law includes several measures intended to increase the state’s ability to protect and better serve survivors.

Security forces must create units specifically dedicated to violence against women. Survivors can now seek restraining orders "without filing a criminal case," an option which did not exist under previous legislation. And the law mandates that survivors receive all necessary "legal, medical, and mental health support," including placement in shelters.

A leader in women's rights?

The passage of comprehensive legislation to eliminate violence against women further cements Tunisia’s reputation as a regional "leader" when it comes to women’s rights. But the importance of the new law largely stems from the troubling levels of violence against women revealed in studies undertaken since the 2010 revolution.

A 2010 report by the Tunisian National Family and Population Office found that 47.6 percent of women – or one out of every two - between 18 and 64 years old said they had been victims of at least one form of violence - physical, psychological, sexual, or economic - during their lifetime.

A 2016 study by the Center for Research, Studies, Documentation and Information on Women in the Ministry of Women, Family and Childhood (CREDIF) additionally found that 53.5 percent of female respondents reported being subjected to some form of violence in public spaces, a number which rose to 58.3 percent in professional spaces.

If effectively implemented, the new law could dramatically change the culture of impunity which surrounds violence against women. But while few question the importance of the legislation, many have criticised the final version of the bill for failing to go far enough.

Although Article 21 of the Tunisian constitution states that "all citizens, male and female alike, have equal rights and duties, and are equal before the law without any discrimination," several discriminatory regulations remain.

More than half a century after its passage, the CSP remains arguably the most progressive personal status code in the Arab world

Inheritance laws rooted in Islamic jurisprudence, for example, still entitle female heirs to half of the property share of their male counterparts. And on a broader level, the Tunisian Personal Status Code (CSP) designates men as “the head of the family”.

Implemented only five months after Tunisia's independence from France in 1956, the CSP was exceptionally progressive for its time: in the words of historian Mounira Charrad, it “profoundly changed family law and the legal status of women.”

CSP reforms included the abolition of polygamy, the establishment of equal divorce proceedings, and the requirement that both spouses consent to marriage. More than half a century after its passage, the CSP remains arguably the most progressive personal status code in the Arab world.

But for many Tunisian progressives, the once revolutionary CSP has outlived its usefulness. In her 2016 book on gender inequality in Tunisia, law professor and researcher Sana Ben Achour argued that the code has “exhausted its historical functions". Now, she said, it serves to uphold a broader “patriarchal model” blocking women’s “equality and full realisation of human rights.”

If the new legislation represents an important step forward, then its failure to address these culturally sensitive issues speaks to the persistence of the “patriarchal model” Achour describes.

New reforms for the future

Less than one month after the passage of the “Elimination of Violence Against Women” law, Tunisian President Béji Caid Essebsi evoked more changes to come.

Speaking on Tunisia’s National Women’s Day and the 61st anniversary of the CSP, Essebsi emphasised the promises of the Tunisian Constitution. He instructed the Ministry of Justice to remove the 1973 memorandum prohibiting marriages between Tunisian women and non-Muslims, announced a committee charged with guaranteeing individual rights and gender equality, and perhaps most notably, spoke of moving towards "equality in inheritance".

Responses to Essebsi’s speech came swiftly. Immediately celebrated by feminist activists and human rights organisations, his announcement gained the support of several progressive political parties and parliamentarians.

Responses were significantly harsher abroad. Egypt’s Al-Azhar, the highest institution in Sunni Islam, condemned Essebsi’s speech: “Islamic texts, including verses from the Holy Quran on inheritance, are fixed provisions. Al-Azhar categorically rejects any attempts to change them.”

Some conservative media outlets and clerics went further. Well-known preacher Wajdi Ghanim, a former prominent member of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood currently living in asylum in Turkey, called for violence against the Tunisian president.

But Essebsi denounced attempts at outside "interference" in the country’s affairs, while the Tunisian minister of foreign affairs quickly voiced his displeasure at Ghanim's statements with the Turkish ambassador. On 13 September, Essebsi implemented one of his promised reforms, announcing the removal of a 1973 memorandum prohibiting marriages between Muslim Tunisian women and non-Muslims.

Regardless, the controversy surrounding Essebsi’s speech highlights the challenge facing Tunisian progressives, as their proposed reforms confront resistance across Tunisia and the wider region.

But if the passage of the Elimination of Violence Against Women law is any indication, progressive Tunisians show little signs of giving up. As the Tunisian Association of Democratic Women stated recently, “We who won the battles of parity, equality, and the elimination of violence against women, will win the current and future battles against patriarchal oppression, no matter what that oppression looks like”.

- Ramy Khouili is a medical student and a dedicated human rghts activist working with several national and international organisations, as well as various UN agencies. His areas of expertise include individual and collective liberties, sexual and reproductive rights, women's rights and gender equality, and the rights of migrants and refugees. Twitter: @khouiliramy

- Daniel Levine-Spound is a second-year student at Harvard Law School focused on international human rights law. His research interests include transitional justice, refugee rights, human rights and counter-terrorism, and international criminal law. Twitter: @dlspound

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

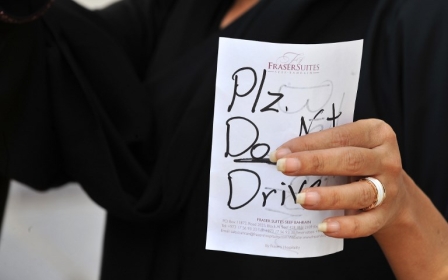

Photo: Tunisian women shout slogans during a demonstration to protest violence against women in front of a court in Tunis where a young Tunisian woman, allegedly raped by two policemen, was due alongside her fiance on 2 October 2012 facing charges of indecency, in a case that sparked outrage in the country. (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].