Iraq should not overplay victory as Kurds' dream lies shattered

October 16, when Iraqi troops captured Kirkuk from the Kurdish peshmerge, will likely go down in Kurdish history as a tragic day, a dividing line between two eras.

A hopeful, rising nationalism, slowly although fractiously inching towards realising the Kurdish dream of statehood, and bitter and angry disillusionment with the political class which, through its mismanagement, partisanship, and corruption supervised the dismantlement of this dream.

Blame game

It is the Kurdish version of the 1967 Arab defeat in the June war against Israel, a devastating psycho-political earthquake delegitimising the then reigning pan-Arabist political order. Ordinary Kurds reacted viscerally to the news of losing Kirkuk and other disputed territories.

Scenes of adults crying, visibly shocked, or simply in a state of disbelief were common. The swift loss of about 40 percent of a united Iraqi Kurdistan, the basis of a future state, needed honest explanations.

The political class offered none, opting for the usual blame game whose principal casualty is the truth, with the two main parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) trading accusations of treason and autocratic decision-making for the Kirkuk debacle.

What Iraq should do is protect the federal framework of its relationship with KRG

The referendum - and its aftermath - exposed the fatal structural weakness in the Iraqi Kurdish political system: the triumph of tribalism over institutionalism where a powerful patronage system, rewarding loyalty and discouraging open debate, reduced the complex institutional decision-making process to a mere individual will.

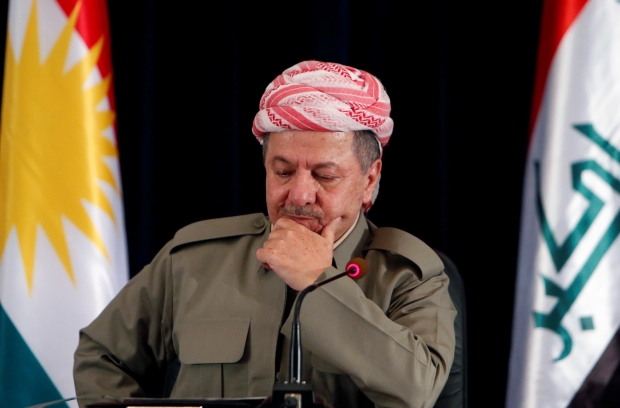

This most disabling aspect of Kurdish politics kicked in when an expired presidency sidesteped an already suspended parliament, unwisely mobilised the deepest nationalist feelings, carelessly disregarded fierce local, regional and international opposition, single-handedly made the important existential decision for Iraqi Kurds and miserably failed to take responsibility for the failure that followed.

The successfully organised referendum also sorely tested Iraqi Prime Minister Haider Abadi.

Faced with an Iraqi public increasingly angry with what it saw as constant Kurdish maximalism and overreaching, and uneasy with his hardline Shia rival party, which is bent on showing him as weak in facing down Kurdish separatism, the usually conciliatory Abadi took a hawkish public stand.

He quickly announced punitive measures against the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) emboldened by an international green light and Iranian-Turkish eagerness to make the proud Barzani pay for an ill-timed referendum. Abadi kept the pressure up, amassing troops to capture Kirkuk, delivering an ultimatum to Barzain who refused to budge.

The post-referendum cataclysm left the Kurdish political class reeling, but, unfortunately, without soul-searching hints, or genuine consideration of the real causes

People familiar with Barzani’s thinking said he did not take the ultimatum about the impending military capture seriously. His back-up plan was for the peshmerga to put up a fierce resistance to the advancing troops long enough to stir an international outcry, embarrassing Washington into forcing Abadi to halt the operation.

But Iran's top official in Iraq, Qassem Soleimani, ensured this did not happen. His arrangements with local political and peshmerga leaders, uncomfortable with Barzani's dangerous brinkmanship, dissuaded them from fighting. The remaining peshmerga that fought could not withstand the punishing fire of a superior Iraqi force. Abadi carried the day.

Contradictory messages

The post-referendum cataclysm left the Kurdish political class reeling, but, unfortunately, without soul-searching hints, or genuine reconsideration of the real causes.

The KDP, the ever disciplined and centralised party, still sticks to its guns: defiant, remorseless, and self-righteous, with confusingly contradictory messages. In one breath, it invokes the victimhood and resistance narrative, calling for street-level action and warning of an approaching genocide against the Kurds.

The obvious fact is that KRG - as a unifying institutional reality for the Kurds - no longer exists. The retreat is towards the old two-administration model: PUK-land and KDP-land

In another, it emphasises peaceful solutions, asking for negotiations with the same government it accuses of organising the genocide. The PUK, its traditional rival, is simply in tatters. Most of its historical leaders are sidelined, helplessly angry or quiet.

The Talabani family tries to restore a sense of order and legitimacy to the party through deals with Baghdad to normalise the situation in PUK-land: opening the airport, paying civil servants and peshmerga salaries, and lifting the government's punitive measures.

But the obvious fact is that KRG - as a unifying institutional reality for the Kurds - no longer exists. The retreat is towards the old two-administration model: PUK-land and KDP-land.

Baghdad holds the most important cards. According to a government insider, Baghdad intends to use its influence through the power of the purse, directly distributing the KRG share of the federal budget, potentially reduced to 13 percent, to the three "Northern Provinces" (Erbil, Sulaimanya, and Duhok), with some federal oversight to ensure transparency and avoid concentrating power and resources in the same old hands, i.e. Barzani.

Can Baghdad do it?

If correctly done, a challenge in itself given Baghdad's checkered anti-corruption history, this will help dismantle the patronage system that presided over the KRG failure. But a Baghdad, euphoric with its unexpectedly easy win, can also overplay its hand.

Sources close to Grand Ayatallah Ali Sistani, Iraq's highest religious authority, told me that Sistani quietly smashed a reckless effort by parliamentarians to impeach the Iraqi president, Fouad Massum, who is originally a Kurd, by putting him on trial later for treason. More reckless are the reported arrest warrants issued by Baghdad, yet not acted on, against Barzani, his son Masrour, and his maternal uncle, Hoshyar Zebari, the principal architects of the referendum.

Such warrants would likely inflame ethnic tensions, showing the central government as vengeful and selective, a sorry throwback to former Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki's counter-intuitive use of the judiciary to eliminate Sunni rivals. The result was the rise of the Islamic State (IS). Such a move would also strengthen the three KDP leaders, turning them into heros in Kurdish eyes.

But the most dangerous temptation to resist is a return to the old centralist ways. What Iraq should do is protect the federal framework of its relationship with KRG, only fine-tuning it to ensure that its Kurdish citizens actually receive the benefits of federal money and services.

Trying to shape Kurdish political realities to Baghdad’s liking, through the usual manipulations and interventions, would be a long-term recipe for disaster. The Kurds should be left to decide their political representation and priorities.

Being magnanimous in victory runs contrary to Iraq's zero-some political culture. But for Iraq to act magnanimously towards its Kurds in their moment of weakness is not only morally right, but politically expedient and strategically beneficial. Can Baghdad do it?

- Akeel Abbas is an Iraqi academic and journalist. He currently teaches at the American University of Iraq at Sulaimanya(AUIS), and holds a Ph.D in cultural studies from Purdue University.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

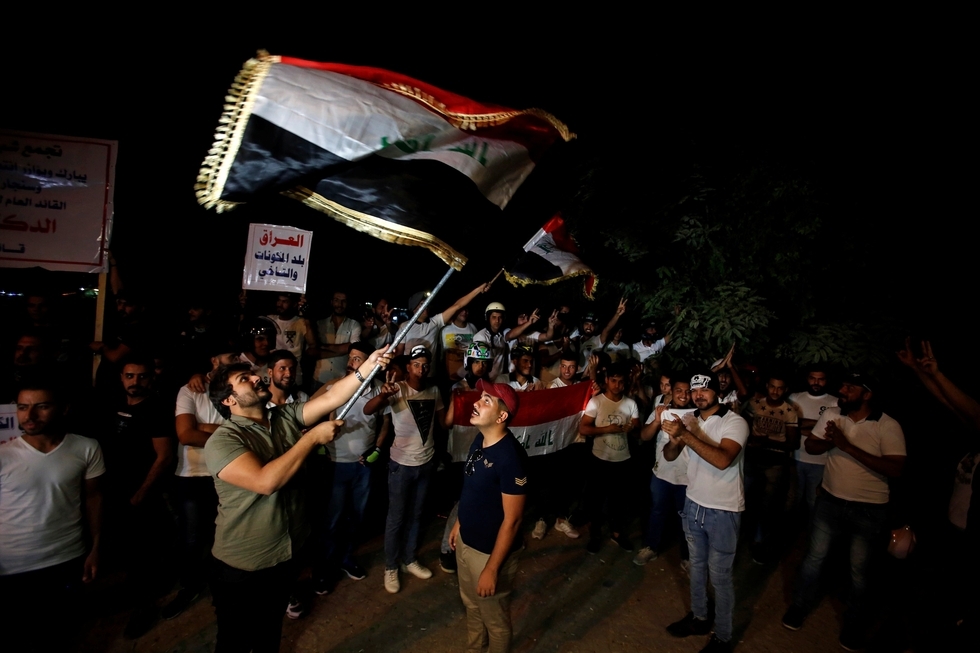

Photo: Iraqi people celebrate after Kirkuk was seized by Iraqi forces as they gather on the street of Baghdad, Iraq October 18 2017 (REUTERS/Khalid al-Mousily)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].