Why the two-state solution refuses to die a natural death

Despite all appearances to the contrary, those in the West who do not want to join the Israeli victory party are clinging firmly to the two-state solution. Israel has increasingly indicated by its deeds and words, including those of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, an opposition to a genuinely independent and sovereign Palestine.

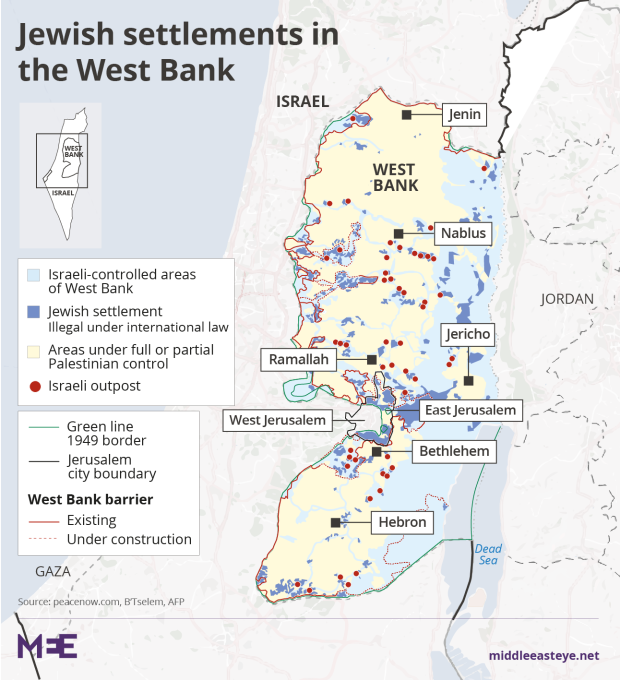

The settlement expansion project is accelerating with pledges made by a range of Israel political figures that no settler would ever be ejected from a settlement even if the unlawful dwelling were not located in a settlement bloc.

Trump, even more than prior presidents, has weighted American diplomacy heavily and visibly in favour of whatever Israel’s leaders seek as the endgame of the epic struggle between these two peoples

On Sunday, Netanyahu's Likud Party unanimously urged legislators in a non-binding resolution on Sunday to effectively annex Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank, land that Palestinians want for a future state.

Clinging to the two-state solution

What is more, Netanyahu, although sometimes talking as if he favoured a resumption of peace negotiations, seems more authentic when he demands the recognition of Israel as the state of the Jewish people as a precondition for any resumption of talks with the Palestinians.

To top it all off, the Trump decision of 6 December last year to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and to follow this up by moving the US embassy withdraws from future negotiations one of the most sensitive issues - the status and sharing of Jerusalem.

All in all, it seems time to recognise three related conclusions: first, the leadership of Israel has rejected the two-state solution as the path to conflict resolution; secondly, Israel has created conditions, almost impossible to reverse, that make impossible the establishment of a Palestinian state.

And thirdly, Trump, even more than prior presidents, has weighted American diplomacy heavily and visibly in favour of whatever Israel's leaders seek as the endgame of the epic struggle between these two peoples.

And yet many people of goodwill and dedicated to peace cling to the two-state solution.

The words of Amos Oz, the celebrated Israeli novelist, express a widely shared sentiment: "...despite the setbacks, we must continue to work for a two-state solution. It remains the only pragmatic, practical solution to our conflict that has brought so much bloodshed and heartbreak to this land."

It is also significant that Oz made this statement in the course of a 2017 year-end funding appeal on behalf of J Street, the voice of moderate Zionism, in the United States.

What Oz says, and is widely believed, is that there is no solution available to Palestine unless there is a sovereign independent Jewish state along 1967 borders as the essential core of any credible diplomatic package.

All alternatives would, in other words, not be "pragmatic, practical", according to Oz and many others. Why this is so is rarely articulated, but appears to rest on the proposition that the Zionist movement, from its inception, sought a homeland for the Jewish people that could only be secured if under the protection of a Jewish state.

For many years the Palestinian leadership has shared this view, and has given its formal blessings since the 1988 PNC/PLO declaration that looked toward the acceptance of Israel if the occupation were ended and Palestine established on the 1967 borders (which were significantly larger than what the UN had proposed by way of partition in General Assembly resolution 181 (that is, Israel would have 78 percent rather than 55 percent of the overall territory comprised by the British Mandate).

This type of outcome also informed the Arab Peace Initiative of 2002 and was confidently depicted as the solution during the Obama presidency.

Even Hamas endorsed its spirit by proposing over the course of the last decade a long-term ceasefire, up to 50 years, if Israel were to end the occupation of the East Jerusalem, West Bank and Gaza, which in effect would materialise the two-state solution in the form of a de facto Palestine.

Serious doubts

There were at least four problems, conveniently swept under the nearest rug by two-state advocates, any one of which is sufficiently serious to raise severe doubts about the credibility of the two-state solution.

First, liberal Zionism expressed an outlook toward a diplomatic settlement that was not shared by the Likud-led Israeli government that has dominated Israeli politics throughout the 21st century.

The Israeli goal involved territorial expansion, especially with respect to an enlarged and annexed Jerusalem, and by way of an extensive network of settlements and transport links in the West Bank, underpinned by the fundamental belief that Israel should not establish permanent borders until the whole of "the promised land" as depicted in the Bible was deemed part of Israel.

In effect, despite some coyness about engaging with a diplomatic process, Israel never credibly endorsed a commitment to a Palestinian state based on the equality of the two peoples.

Secondly, Israel created extensive facts on the ground that have definitively contradicted its professed intention to seek a sustainable peace based on the two-state solution.

Thirdly, the two-state solution as envisioned by its supporters effectively overlooked the plight of the Palestinian minority in Israel, which amounts to 20 percent of the population, or about 1.5 million persons.

To expect such a large non-Jewish minority to accept the ethnic hegemony and discriminatory policies and practices of the Israeli state is unrealistic, as well as being contrary to international human rights standards.

And lastly, beyond this, to sustain Israel in relation to the dispossessed and oppressed Palestinian people has depended on establishing structures of ethnic domination that constitute the crime of apartheid.

Dismantling apartheid structures

As in South Africa, there can be no peace with the Palestinians until the apartheid structures used to subjugate the Palestinian people as a whole are dismantled (including those imposed on Palestinian refugees and involuntary exiles), and this will not happen until the Israeli leadership and public give up their insistence that Israel is exclusively the state of the Jewish people, with an unlimited right of return and other privileges based on ethnic identity alone.

All this pushes us to discard the two-state solution as unwanted by Israel, normatively unacceptable for the Palestinians and not diplomatically attainable even if a strong political will unexpectedly emerged that was genuinely dedicated to its implementation.

Against this critical background, we are obliged to do our best to answer this haunting question - is there a solution that is both desirable and attainable, even if not presently visible on the political horizon?

Following these lines, prefigured 20 years ago by Edward Said, two overriding principles must be served if a sustainable peace is to be achieved: Israelis must be given a Jewish homeland within a reconfigured Palestine and the two people must allocate authority in ways that uphold the cardinal principles of collective equality and individual human dignity.

Operationalising such a vision would seem to necessitate the establishment of a secular unified state maybe with two flags and two names. There are many variations, provided there is respect for the equality of the two peoples in the constitutional and institutional structures of governance.

If the liberal Zionist approach seems impractical and unacceptable, is this preferred alternative "an irrelevant utopia" that is at best a source of false hopes?

If the Palestinians were to propose such a solution in the present political atmosphere, Israel would either ignore or react dismissively, and much of the rest of the international community would scoff. Perhaps, but what is being proposed is a relevant utopia, and the only realistic path to a sustainable and just peace.

There is no doubt that the present constellation of forces is such that an initial dismissal is to be expected.

Although if the Palestinian Authority were to put this vision forward in the form of a carefully worked out proposal, it would give fresh ground for a debate more responsive to the actual circumstances faced by Israelis, as well as Palestinians.

A global solidarity movement

The prime political and ethical question is how to create political traction for a secular state shared equally by Israelis and Palestinians.

It is my view that this can only happen in this context if the global solidarity movement mounts sufficient pressure on Israel so that its leadership recalculates its interests.

The South African precedent, while distinctive, is rather instructive. Few imagined a peaceful transition from apartheid South Africa to a constitutional democracy based on racial equality until after it happened.

I envisage a comparable potentiality with respect to Israel/Palestine, although undoubtedly there would also be a series of factors that established the originality of this latter sequence.

In politics, if will and capabilities are present and mobilised, the impossible can and does happen, as it did in South Africa and in struggles against the European colonial regimes in the latter half of the 20th century.

Further, without such a politics of impossibility, massive suffering will persist. The path to genuine peace and justice for both Palestinians and Israelis needs to be based on them living together on the basis of mutual respect under a mature and democratic version of the rule of law, underpinned by checks and balances and constitutionally anchored fundamental rights.

- Richard Falk is an international law and international relations scholar who taught at Princeton University for 40 years. In 2008 he was also appointed by the UN to serve a six-year term as the special rapporteur on Palestinian human rights.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Israeli security forces detain a Palestinian youth in Jerusalem's Old City (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].