Will holding elections in 2018 end Libya's conflict?

On 29 November, United Nations special envoy to Libya Ghassan Salame stated that the UN mission was working on holding elections in Libya before the end of 2018.

The announcement came shortly after delegates from the Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HOR) and the Tripoli-based Higher Council of State (HCS), held two rounds of UN-sponsored negotiation meetings in Tunisia to agree on amendments to the Libyan Political Agreement (LPA).

Talks, however, ended in a deadlock with no deal reached.

Without a strong impartial security mechanism in place and judicial institutions overseeing and safeguarding the outcome, elections would be meaningless

Holding elections has been the buzz word in Libya during the last weeks of 2017 but without a clear idea on which elections (parliamentaty, presidential) and when exactly.

Possible options

The failure of the two transitional political entities (HOR and HCS) that represent the main political divide in Libya to agree on a way forward seemed to be the motive behind the UN envoy's attempt to shift priority to other possible options.

These options include plans for holding a large national reconciliation conference in 2018 and heading straight to the polls to replace the current political bodies.

When addressing the Security Council on 15 November, Salame reiterated the idea of a national conference, slated for February 2018, that "will give Libyans, from all across the country, the opportunity to come together in one place, renew their common national narrative, and agree on the tangible steps required to end the transition".

However, this may still be a political leverage to exert pressure on both the HOR and the HCS to make the necessary compromises for a breakthrough.

A national reconciliation conference could only convene later in the year as a culmination of many important local and regional reconciliations within Libya that need to take place first.

There is a general apathy among Libyans towards the idea of any election due to a general belief that it is not likely to make much difference to their lives

The UN envoy's call for new elections looks more like a leverage rather than a well-constructed plan due to the lack of a clear explanation of the basis for these elections. Will the elections be held following the approval of a new permanent constitution, a move that Libyans have been aspiring for?

If so, then elections can only take place once the new constitution is approved by a two thirds majority of the Libyan people in a direct referendum. Or will it be yet another fourth transitional period to elect new temporary political entities and only replaces current faces with new ones.

This move will only prolong an already turbulent transition marred with conflict and civil wars without addressing and resolving the root causes of the Libyan conflict.

Only recently, Libyans experienced going to the polls for the first time following four decades of Muammer Gaddafi's authoritarian rule during which elections were never permitted. Within two years (2012-2014), four elections took place including electing two consecutive parliaments as well as electing local municipal councils and a constitution-drafting body made up of 60 members.

The largest voter turn-out, nearly three million people, took place during the first elections, held following the 2011 revolution, to elect a parliament in July 2012, in which nearly all eligible voters registered to vote.

People were excited about exercising a right they had been denied for decades and all the change for the better that it might bring.

Key questions unanswered

However, today the picture is totally different. People are exhausted by the ongoing conflict and violence, lack of security as well as dire socio-economic conditions associated with it. There is a general apathy among Libyans towards the idea of any election due to a general belief that it is not likely to make much difference to their lives.

Additionally, providing a secure environment for elections is also a major challenge. Kidnapping and assassinations have been almost a weekly occurrence; this is highlighted by the very recent assassination of the mayor of Misrata, Mohamed Eshtewi, who was a high-profile figure advocating peace, reconciliation and political accord.

Therefore, the UN's call for elections in Libya in 2018 without addressing the underlying causes of violence and instability is effectively putting the horse before the cart.

The UN left key questions unanswered, such as who is going to provide security for a free peaceful election? Will the armed groups, that wield the real power in the east and west of the country, respect the free will and choices of the people, or will they interfere in the process to impose their own preferences?

Are elections a goal in themselves, or should they constitute a final stage following more crucial phases of reconciliation and consensus-building based on a social contract for power and wealth sharing?

Without a strong impartial security mechanism in place and judicial institutions overseeing and safeguarding the outcome, elections would be meaningless and even a retrogressive step that may lead to more divisions and violence.

During the 2017 Mediterranean Dialogues, held on 29 November, Salame gave an extensive interview in which he explained at length his overall plan and where elections fit into it.

He stated that Libyan elections will be held in 2018 only if conditions were right. He clearly expressed his wish that Libyans should not have to endure yet another new transition – but to move to permanent institutions around three things: a constitution, national reconciliation and elections.

Salame emphasised that elections in Libya should be a solution to the problem and not the source of new problems! He added that four conditions must take place before elections can occur - technical, legislative, political as well as security conditions.

Another new transition

In response to technical conditions, on 6 December, Salame announced, during a joint press conference with Libya's High National Election Commission (HNEC), the start of voter registration in Libya as a preparation for elections once they are called.

The voter register in Libya has not been updated since the last elections in 2014. It is estimated that 4.5 million are eligible to vote today, yet less than 1.5 million are already registered to vote from the last election in 2014.

The commission aims to register at least 2.5 million, which is more than half of those eligible. This target, however, may take many months to achieve which makes holding elections in the coming few months highly unlikely.

The opening of voter registration has indeed galvanised the political debate in Libya with a clear shift in narrative towards possible elections that may end the stagnation and clear the political impasse that Libya has been enduring.

A narrative shift

Extensive discussions on social media have shifted from wars and conflict to debating whether elections should take place before or after a referendum on a new permanent constitution.

Competing factions have been rallying their supporters to register for voting. General Khalifa Haftar has recently urged his supporters to prepare for elections. This could indicate that he might have abandoned his military strategy of taking over power in Libya by force in favour of a political track in which he could stand for elections.

This shift by Haftar seems to come as a result of international pressure and persuasions by countries such as Italy and Egypt, his key backer, amongst others.

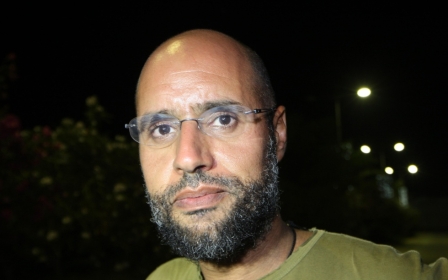

Gaddafi's loyalists are also advocating voter registration with several media reports purportedly suggestig that Gaddafi's son, Saif al-Islam, would stand for presidential elections on a promise to provide "security and stability".

The fact that his loyalists are taking to elections is a reflection that they are inevitably accepting a new political era and order in Libya based on constitutional rule and democratic elections.

Despite this euphoria about elections, Saif al-Islam may be prevented from nominating himself since he has been indicted by a court in Libya and is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes.

There is no doubt that shifting the debate in Libya to elections is a positive step forward on the road to end a deep conflict and a volatile troublesome transition. The ideal scenario, in the coming months, however, is for the UN to steer Libyans towards a referendum on a new permanent constitution possibly before the end of 2018, followed by permanent presidential and parliamentarian elections in the first half of 2019.

This requires key underpinning elements which include the political will by regional and international players, cessation of all wars and violence, much improved security and socio-economic conditions and finally, a consensus amongst all Libyan factions to reconcile their differences and converge together to build a country that has so many intrinsic, strong factors in its favour.

- Guma El-Gamaty is a Libyan academic and politician who heads the Taghyeer Party in Libya and is a member of the UN-backed Libyan political dialogue process.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye

Photo: Within two years (2012-2014), four elections have taken place (AA)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].