Meet Yemen's street artist: 'We want peace'

SANAA - Murad Subay sees the devastated streets and bombed buildings in Yemen's war as something more than just ruins: he sees canvases onto which he can tell stories through art.

The award-winning 30-year-old street artist's aim is to spread a message of peace during Yemen’s current crisis - and his work is having a major impact in Yemen and abroad.

“Street art has never really been a part of Yemeni culture, but after seven years of war, it is becoming more normal,” he tells Middle East Eye.

“I’m not working for any side or for my own power,” he says. “I am against the war. We only hear about explosions or the voices of hatred, and doing art in times of war means we want peace.”

Highlighting the harsh realities of today's war-torn Yemen, Subay's murals adorn burnt-out buildings and walls across some of the country's biggest cities including the capital Sanaa, the southwestern city of Taiz, and the coastal city of Hodeida.

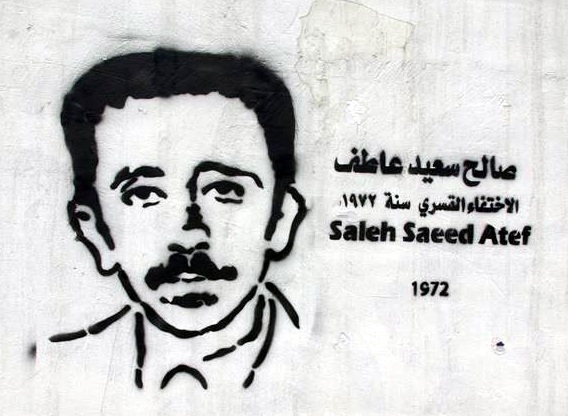

His depictions tackle issues such as the forced disappearances of civilians, the current cholera epidemic, and the ongoing misery inflicted by both sides on innocent civilians.

Experts say his work is having a powerful impact on Yemeni society. Dr Anahi Alviso Marino, a Paris-based political scientist, has done extensive research on street art in Yemen and the role Subay has been playing.

“His campaign on the forced disappearances, for example, pushed the issue onto the political agenda. It also helped to find and locate some of the people who had gone missing. People were found because of the images he had stencilled,” she adds.

People were found because of the images he had stencilled

-Dr Anahi Alviso Marino, political scientist

According to a 2017 report from Human Rights Watch (HRW), dozens of people have been forcibly disappeared.

Subay says that the role of street art is more important in times of war than during times of harmony.

“During times of peace, everything existed but today people are losing their voices, their lives, their hope," he says. "When you walk down a street in Yemen today, you will only see disappointment on people’s faces. They don’t believe in any side of this war. They just want to eat and have access to clean water. But there is cholera and diphtheria, and a million people facing hunger and malnutrition."

The United Nations says that Yemen is the world's worst humanitarian crisis, with eight million people "on the brink of famine and a failing health system".

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the cholera epidemic in the country has become the largest and fastest-spreading outbreak of the disease in modern history.

At the end of 2017, a million cases were expected, with at least 600,000 of that figure likely to be children, according to the WHO.

The organisation has also reported that nearly 500 people have been infected with diphtheria, a preventable disease that was thought to have been eradicated.

Childhood dreams

Subay was born in the city of Dhamar in the southwest and moved to Sanaa when he was six years old.

From an early age, he started showing an interest in art and he grew up reading books about famous European painters like Pablo Picasso, Vincent Van Gogh and Henri Matisse.

With the encouragement of his family, Subay began painting and teaching himself art skills at home.

Yet with formal art courses only available in Aden and Hodeida and not in the capital, Subay went on to study English literature at Sanaa University.

In 2011, the uprising against Ali Abdullah Saleh's government inspired Subay to take his art to the streets.

“I wasn’t ever thinking that I would do street art. I didn’t really know that it existed,” he says.

Subay joined thousands of protesters at Tagheer Square in Sanaa, chanting for "human rights and justice."

Today people are losing their voices, their lives, their hope

- Murad Subay, street artist

“When it looked like the revolution was going to fail, people grew frustrated, especially those who had been dreaming of a better life. I was also frustrated and that’s when I began drawing on the streets of Sanaa,” he says.

A year later, he launched his first street art campaign called "Colour the Walls of Your Street," inviting people through social media to participate in an event to paint over the effects of the shelling and bullets on walls. Many people from his community - the young, the old, artists, non-artists, came together for the event, painting a variety of images from flowers to designs, to non-descript objects.

It was launched in 2015, in the Bani Hawwat area of Sanaa, where air strikes destroyed more than seven houses and killed 27 civilians, including 15 children, according to Subay’s campaign.

The UN says the prolonged war has already claimed the lives of more than 5,000 civilians in less than three years. Due to the dangers, Subay has often found himself caught in the crossfire with authorities.

“I once went to Taiz during a time when it was being heavily bombarded by air strikes and mortar shells,” he recalls. “I had just finished painting some water murals when we were caught.”

“The authorities kept us for around an hour, and only released us on the condition that we would return to Sanaa. Another time, when we went drawing in a dangerous part of Sanaa, we were kept in a cow pen made of mud for around one hour [as well]."

To lessen any possible risks with authorities, Subay seeks permission to paint on buildings from their owners.

“It isn’t necessarily illegal to do street art, but given the dangerous times we live in, I always get permission from people who own the buildings that I draw on,” he explains.

“Initially, Yemenis, who are sceptical of most things because of the war, weren’t sure about what I was doing. So I’ve had to do my best to show that I’m independent and that I want to express what this means for our people.”

Politics is not just impacting his professional life - his personal life is also under pressure from Yemen's current situation.

Subay's wife Hadil, 23, is currently on a scholarship studying international law at Stanford University in California. But US President Donald Trump's travel ban, which was announced in January 2017, has kept the couple apart.

“It's been one year since I've seen my wife. She is scared to leave the US in case they don't let her back in, and I'm not allowed to visit her,” he says.

It's been one year since I've seen my wife

-Murad Subay, street artist

His artwork has attracted global attention, as he is often called the pioneer of the street art scene in Yemen and the "Arab Banksy".

Yet Marino says that this description does not completely reflect Subay’s work. She explains that Banksy is much more of a solo artist, while Murad's work is more of a collaborative effort that brings the community together.

He has drawn a mural in London reflecting how the international community is ignoring the human rights violations and atrocities taking place in Yemen. But because of the war, Subay says that he has missed at least 15 opportunities to speak about or showcase his work.

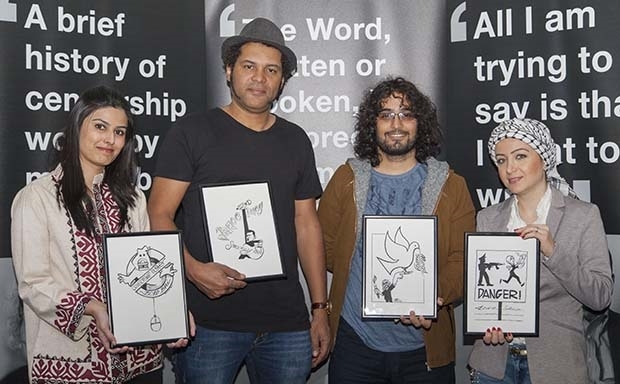

In March 2017, he collaborated with UK-based artist Lisa-Mari Gibbs on the anniversary of the first "Colour the Walls of Your Street" campaign.

Both artists hosted an "open day of art" simultaneously in Sanaa and Reading, a city in the UK.

During the day, groups in the two countries were given the opportunity to express themselves through art, with the overarching theme of promoting peace.

People don’t believe in any side of this war. They just want to eat and have access to clean water. But there is cholera and diphtheria, and a million people facing hunger and malnutrition

- Murad Subay, street artist

Almost one year later, Subay is keen to see the event grow.

“Last year a bridge was built between Yemen and the UK. This year I’m working on building new bridges with places like Milan, New York and South Korea to see if artists in those countries would like to participate in the 'open day for art',” Subay says.

With restricted access for foreign journalists and local journalists facing pressure on the ground in Yemen, international news outlets are struggling to tell the story of the dire humanitarian situation in the country.

Subay says that his murals and the small street art scene that is developing in the country could have an impact on getting their stories out.

For Subay, however, his main concern is his fellow Yemenis.

“Street art has never really been a part of Yemeni culture, but after seven years of war, it is becoming more normal,” he says. “What is art in the streets going to do to help? It’s not going to feed people, but it is work to feed people; it’s work to give them hope, to give them a voice.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].