Should Britain's Matthew Rycroft take the blame for UN failure in Yemen and Myanmar?

This month one of the rising stars of the British diplomatic firmament steps down from his post as our representative at the United Nations after three years' service. Matthew Rycroft, who moves on to a new job as permanent secretary for overseas development next week, has been showered with praise from top people.

I will ask an unusual question. Was Matthew Rycroft worth this adulation?

Moral judgment

Two tragedies have dominated Rycroft's time at the UN since he joined in April 2015. The first was the war in Yemen, while the second is the genocide in Myanmar.

Tens of thousands have died in these twin calamities. More die every day. Millions have fled their homes and millions face starvation.

Rycroft was "penholder" at the UN Security Council on both Myanmar and Yemen. This term means that it was his responsibility to lead discussion and draft resolutions on both countries.

So let's take a look at how Rycroft has performed his duties. In this discussion I will not simply apply the standards of the mutual congratulation society that often defines personal dealings in the diplomatic sphere.

Instead I will also apply moral judgments which are appropriate to life and death decisions made in comfortable offices in cities like New York and London - yet have profound effects on far off places.

Two tragedies have dominated Mr Rycroft's time at the United Nations since he joined in April 2015. The first was war in Yemen, while the second is the genocide in Myanmar

I turn first to Yemen. The war was sparked in March 2015 when the Houthis swept down from the north and drove Yemeni President Abd Rabbou Mansour Hadi out of the capital, Sanaa.

A month later Rycroft started his new job at the United Nations. During his period in charge, Britain has continued to sell arms to Saudi Arabia while using diplomatic muscle to fend off attempts to give proper scrutiny to the Saudi coalition's merciless bombing of Yemen.

A heavy responsibility

In September 2016 the UK opposed an attempt by the Netherlands to set up a full-scale international inquiry that could lead to the Saudis being referred to The Hague for war crimes.

In the Security Council, where Rycroft is penholder, no resolution has been passed on Yemen, apart from the annual renewal of sanctions on the Houthis. In October 2016, Rycroft did promise to draft a resolution demanding a ceasefire after a Saudi attack on a funeral killed 140 people.

But the resolution never appeared. The website Security Council Report, which is sponsored by a number of governments as well as the Ford Foundation, blames the failure on "pressure from Saudi Arabia".

To sum up, during the Rycroft years United Nations has failed to call Saudi Arabia to account for the havoc that it has wreaked on its helpless neighbour. I believe that we, in Britain, bear a heavy responsibility for the ongoing humanitarian calamity that the head of the UN’s human rights agency predicts could become "the world's worst humanitarian disaster for 50 years".

Myanmar's genocidal violence

Now let's turn to Myanmar. Though the persecution of the Rohingya Muslims dates right back to Myanmar's independence from Britain in 1948, two recent events sparked the latest horror.

In October 2016, a low-level attack by Rohingya militants on border posts in which nine police officers were killed sparked a crackdown by the Myanmar army that forced 87,000 to flee to Bangladesh.

To his credit, Matthew Rycroft has consistently called for Security Council briefings on the subject of Myanmar

Then in August last year the army responded to a further attack with a wave of genocidal violence in which thousands have been tortured, raped and killed and 650,000 more Rohingya have escaped to Bangladesh.

To his credit, Matthew Rycroft has consistently called for Security Council briefings on the subject of Myanmar.

In October 2017, Britain and France wrote a draft Security Council resolution calling on the Myanmar authorities to "immediately cease military operations" and allow refugees in Bangladesh to return to Myanmar.

But fearful of a Russian or Chinese veto, Britain and France eventually settled on a weaker statement which called on Myanmar "to ensure no further excessive use of military force in Rakhine State".

This was a pathetic response to a terrible situation which informed judges compare to the Srebrenica genocide two decades ago.

In November, Britain also voted in favour of a UN General Assembly resolution calling on Myanmar to end military operations that have "led to the systematic violation and abuse of human rights".

But none of these statements were legally binding and by the time of the November resolution the worst of the killing was over.

In any case Myanmar has no legal obligation to meet UN demands. All this means that, as of today, the UN has done nothing to punish the Myanmar government. It has not even placed sanctions on Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and his army.

But Rycroft cannot take the blame. The only way that the UN could punish Myanmar with sanctions would be if the Security Council recommended it, and that's impossible with China and Russia backing up Myanmar with their veto.

There has nevertheless been a serious failure by the UN in Myanmar to engage robustly with the government about its genocidal persecution of the Rohingya.

Public advocacy in particular has been lacking with all but the UN's rights agency OHCHR speaking in terms of appropriate alarm about the disaster that has unfolded. Emanuel Stoakes and I warned of UN complicity with the regime in our report for Middle East Eye early last summer, well before the latest killings began.

UN complicity?

A BBC report on the issue alleges that the chief UN diplomat inside Myanmar undermined staff who warned that fresh violence was on the way, while a Guardian article indicates that the UN even suppressed internal reports that argued the same thing.

And all the while the UN has played softball with the genocidal government and military of Myanmar. To sum up, the United Nations has stood idly by. This means that it has blood, it should be said a great deal of blood, on its hands.

The UN record during the last few years in Mr Rycroft's two areas of responsibility is so dire that it recalls the League of Nations failure over Abyssinia in the 1930s

I am sure that diplomats would defend Matthew Rycroft on the grounds that he was carrying out the policy of Her Majesty's government while operating within the collegiate constraints of the UN Security Council. Nor does he run the United Nations.

And it was Foreign Office Minister Mark Field, not Rycroft, who made that dreadful speech during the worst of the killing on the floor of the House of Commons which came unnervingly close to laying blame for the Rohingya genocide at the victims' feet.

And the decision to carry on supplying arms to Saudi Arabia was nothing to do with Rycroft. In any case, ultimate responsibility lies with the prime minister and foreign secretary, not diplomats.

And yet taking orders is not a wonderful excuse in the face of two calamities that have claimed so many lives and caused such misery. The UN record during the last few years in Rycroft's two areas of responsibility is so dire that it recalls the League of Nations failure over Abyssinia in the 1930s.

Moral agents

Diplomats are moral agents as well as technicians. The contrast between Sir Robert Vansittart, permanent secretary of the Foreign Office and a powerful opponent of appeasement and British ambassador in Berlin, Nevile Henderson, a keen supporter, is one famous example.

Roger Casement, the British diplomat who blew the whistle on the Belgian atrocities in the Congo and was later hanged for treason during the 1916 Easter uprising, shows what can be done by an upstanding individual with integrity.

For that matter, I have always felt that Craig Murray, the ambassador to Uzbekistan who resigned after his complaints about British complicity in torture were ignored, has never been given the credit he deserves for blowing the whistle.

It may be that when the records are published, historians will discover that Matthew Rycroft has been fighting a behind-the-scenes battle to stiffen up British and UN policy. He may yet emerge as an unsung hero of this inglorious period in the history of the British foreign office.

But let's not forget the notorious Downing Street memo in the summer of 2002 which recorded that, concerning Iraq, "the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy" and all but committed Britain to war.

This memo, which certainly had the air of being written to please his Whitehall masters, was written by a talented young diplomat called Matthew Rycroft. Now Rycroft is set for a further promotion. He is off to be permanent secretary at the Department for International Development (DFID).

DFID versus FCO

This appointment is laden with an irony which no novelist would dare to invent. At DFID he will have to deal with the consequences of FCO and United Nations failures in both Yemen and Myanmar.

I’ve been to the refugee camps in Bangladesh, where I was told of the good work being carried out by DFID. However, a report from MPs today has slammed the British government for being "unacceptably" slow in dealing with the catastrophe in Myanmar.

I hope Mr Rycroft goes to Cox's Bazar soon to see for himself the human tragedy that is (in part) the result of UN inertia. Rycroft will also have to deal with the consequences of one other legacy from his time at the United Nations.

Two weeks ago the Donald Trump administration threatened to drastically cut aid to Palestine.

Rycroft and the British government have responded to the decision with deafening silence. Yet the fallout will be catastrophic for the region and for US and UK interests. There are two million Palestinian refugees in Jordan, nearly three million in Palestine and half a million in Syria.

As Mick Dumper, professor of Middle East politics at Exeter University, has demonstrated, Trump's decision will at once put hundreds of thousands of children out of school, leave 1.7 million refugees without their necessary food and cash assistance and destroy decades of progress with recreational programmes, disability support and microfinance programmes.

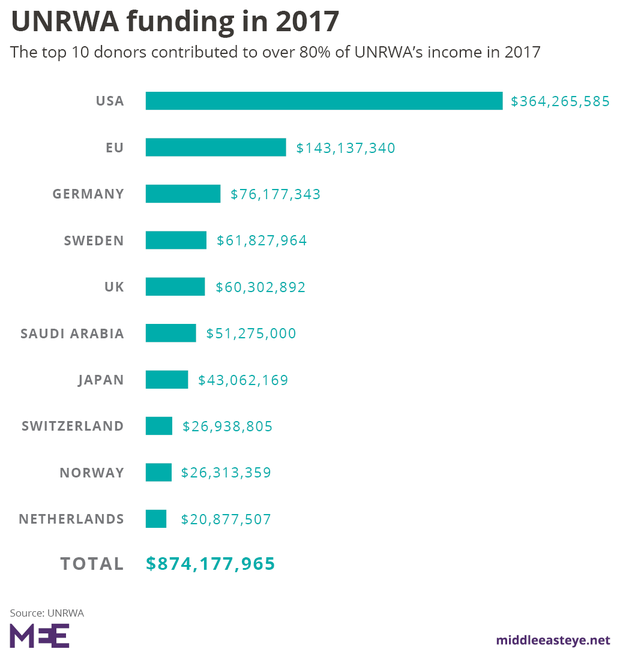

The UK is the third biggest donor to UNRWA's core programmes. The US has threatened that its cuts could be accompanied by demands that other donors make up the shortfall. DFID will have to deal with the ensuing crisis. One wishes Rycroft well in dealing with an international crisis about which he and the FCO has remained notably silent at the UN.

I have also been told that a feud is rumbling between the FCO and DFID about British policy in Yemen. DFID civil servants are angry that British diplomacy – for which their new boss Matthew Rycroft was in part responsible - has not done enough to prevent the killings.

Meanwhile the FCO is loyal to its Saudi allies and fearful of upsetting the boat in Myanmar. Matthew Rycroft will indeed face a conflict of loyalties when he starts work and gets to grips with the human consequences of the failure of Britain and the United Nations in Myanmar and Yemen.

- Peter Oborne won best commentary/blogging in 2017 and was named freelancer of the year in 2016 at the Online Media Awards for articles he wrote for Middle East Eye. He also was British Press Awards Columnist of the Year 2013. He resigned as chief political columnist of the Daily Telegraph in 2015. His books include The Triumph of the Political Class, The Rise of Political Lying, and Why the West is Wrong about Nuclear Iran.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Britain's Ambassador to the UN Matthew Rycroft speaks after voting on new sanctions against North Korea during a Security Council meeting on December 22, 2017, at UN Headquarters in New York City (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].