Can political satire survive in Sisi's Egypt?

Once upon a time, a man found a magic lantern. After he rubbed it, a genie appeared and asked what he wished for.

The man said: "I want a bridge to connect Cairo to Aswan [about 800km]." The genie said: "Well, that's a bit too hard for me; ask for something else."

The man then asked the genie to end Hosni Mubarak's rule. The genie replied: "So do you want the bridge one-way or two-way?"

Political jokes and satire have long been the main, and usually the only, way for Egyptians to vent their frustrations without ending up behind bars. In a country that has either been under semi-military or military rule since 1952, save for one year of Muslim Brotherhood rule, poking fun at the ruling elite - especially the president - has become something of a national hobby.

Different rulers have given Egyptians different contexts and reasons to poke fun at them. Nevertheless, political oppression and the general lack of freedom of expression have prevailed as essential components of Egyptian satire, as these have always been, to varying degrees, part of the country's social and political fabric.

In his book Some of My Memories, prominent Egyptian journalist Amr Abd El Samie noted that political satire flourished during the rule of late President Gamal Abdel Nasser, primarily touching on issues related to the Egyptian intelligence service's control over the government and the repression of political dissent. Political jokes flourished during that time because Nasser had many enemies from across the social and political spectrums, Samie pointed out.

The system that couldn't handle a satirical TV show will certainly not handle this kind of raw and graphic humiliation of its president

Opposed by communists, leftists, liberals, and aristocrats who lost ownership of their estates all over the country, Nasser had jokes coming at him from all directions. In one popular joke, one person says: "One of my friends had one of his teeth removed through his nose." His friend replies: "Why not through his mouth?" The first person says: "Nobody can open their mouth now." ("Opening one's mouth" is a way that Egyptians describe the act of objecting to something.)

In another joke, during one of Nasser's speeches, an attendant sneezes. Nasser asks: "Who sneezed?" After getting no answer, he orders that the first row be shot. He then asks again: "Who sneezed?" Again receiving no answer, he orders that the second row be shot. After he asks a third time, one of the attendants replies: "It was me, Mr President," to which Nasser replies: "Bless you."

In Nasser's footsteps ‘with an eraser'

Anwar Sadat, who became president after Nasser, also received his fair share of mockery. One popular joke was based on Sadat famously saying that he was "walking in Nasser's footsteps" - to which Egyptians added, "with an eraser".

Another joke came in the context of Sadat's decision to postpone the military effort to recapture the Sinai Peninsula, which was under Israeli occupation at the time. It references an arbagi (horse-driven cart operator) who is stalling traffic on a bridge, even though there are no cars ahead of him. A person comes up and asks why he stopped, to which the arbagi replies: "Ask the donkey [Sadat]."

Nasser and Sadat also both received their fair share of criticism through songs, poems and books. Oud player and singer Sheikh Emam, alongside poet Ahmed Fouad Negm, together performed pieces such as Four Who Will Surely Go to Hell, referring to four members of the post-1952 coup Revolution Leadership Council, including Nasser. Another piece called The Thing criticised Sadat's open-market policies in the aftermath of the Camp David Accords, suggesting Sadat was high on hashish when making his decisions.

Mubarak also received a great deal of mockery that mainly revolved around his three-decade rule. In a joke that was popular around election times, Mubarak is asked if he's going to bid farewell to the Egyptian people, to which he answers: "Why? Where are they going?"

Government crackdown

Recently, a very odd sound has become more and more prevalent in the streets of Cairo, particularly in lower-income areas: the sound of two balls clacking against each other. The clacker, made of a ring holding two strings with balls attached to the end of each, has been nicknamed "Sisi's balls". The toy has become a hit among poorer children, but it has not been sold in Cairo's posher areas, which tend to have a larger police presence and people are less welcoming of this type of humour.

Last November, Giza's security directorate released a statement noting that security forces had arrested 41 sellers and confiscated 1,403 pairs of the new toy in order to "maintain security, order, public morals, in addition to protecting lives". The statement added that the crackdown aimed to "stand against the negative behaviour that was affecting children and the psyche of citizens".

Two important observations can be made regarding this. First, the ministry's statement did not mention the actual street name of the toy, which would involve putting the words "balls" and "Sisi" together – something no official would dare to do. Second, the confiscation actually brought more attention to the toy, drawing it to the attention of many who had never previously heard of it.

Such actions by the regime, targeted at ultimately harmless behaviour, tend to stir a great deal of sarcasm when contrasted with the regime's miserable failure in beating terrorism, especially in the Sinai Peninsula.

The system that couldn't handle a satirical TV show will certainly not handle this kind of raw and graphic humiliation of its president.

The furore over "Sisi's balls" represents a very interesting turn in the way Egyptians poke fun at their rulers. It is worth noting that the users of this toy are mainly children, a byproduct of the revolution that opened up politics to all Egyptians.

The rise of "Sisi's balls" has many elements. There is the obvious element of money: people living in a country experiencing dire economic conditions are paying for a toy based on political innuendo. Presence is another important element: the clacking in the streets is a faint reminder of the chanting during the revolution, and the toy represents a collective will to interact with the moment, albeit timidly.

The last, and arguably most important, element is the toy's name, which represents a degree of courage to demean and degrade the president and everything he represents.

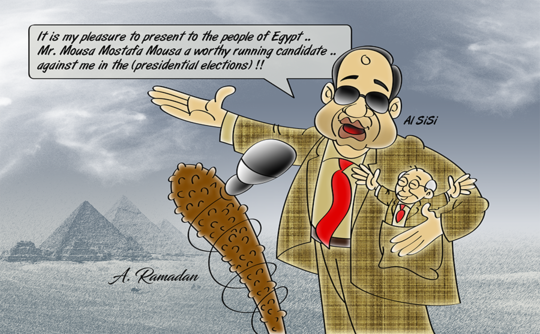

Egypt's tipping point

At the same time, Saeed Sadeq, a professor of political sociology at the American University in Cairo, has highlighted a current shortage of jokes about the president. Sadeq told Masr Al Arabia, a website which is blocked in Egypt, that political jokes have not disappeared, but rather been supplanted by Egyptians using social media to directly criticise the state of their country.

This development comes as everyday life in Egypt has become increasingly difficult. Economic reform measures undertaken by Abdul Fattah al-Sisi's government have knocked the air out of the Egyptian people, even as the government has promised better days ahead.

In 2017, Egyptians experienced extreme price hikes affecting their everyday lives. The price of subway tickets doubled from 1 EGP to 2 EGP ($0.05-$0.1) and is set to increase again in 2018. The price of butane gas cylinders for cooking increased by 100 percent, from 15 EGP to 30 EGP, and the price of gasoline also increased significantly, impacting the prices of food and public transportation. Prices for cigarettes and mobile phone recharge cards have also shot up.

According to statistics from CAPMAS, the Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics, 28 percent of the population was living in poverty in 2015, up from 26 percent in 2012. In July, inflation surpassed 34 percent, its worst in 30 years, while public debt reached $322mn).

While difficult living conditions do drive people to vent using satire and comedy, it seems that Egyptians in general have reached a tipping point, where things simply aren't funny anymore.

The current government has done things that are unprecedented in Egypt's history, and it seems that this shock therapy has left most people numb. From the the handing over of Red Sea islands to Saudi Arabia, to the evacuation of Sinai cities and villages, to the aforementioned economic measures, Egyptians have been severely disoriented.

Ongoing attacks by armed fighters have added to the chaos. According to Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies, between 2015 and 2017, a total of 1,165 "terrorist" operations were carried out in Egypt.

On 24 November 2017, Egypt witnessed one of the deadliest terrorist attacks in its history. Fighters reportedly carrying Islamic State flags attacked al-Rawda mosque in northern Sinai, killing 305 people and injuring 128.

The role of social media

Amid this backdrop, social media has transformed the way young Egyptians express themselves. In a country where half of the population is below 25, and where 17 million people use Facebook, social media has arguably become a last resort for expressing opinions relatively freely. Egyptian authorities have blocked hundreds of websites, and the country has become the world's third-worst jailer of journalists.

Facebook in particular has given birth to new ways of making fun of the system. Memes, comics and fictional scripts have gained prominence. Satire has become more sophisticated, with more layers and innuendos. In a society where words can put you in jail, or even get you killed, dark sarcasm has become a go-to coping method.

Mohamed Andeel's Big Brother online satire show appeals both to intellectuals, with its Orwellian reference to the regime, and to working-class Egyptians, as the name is also a basic reference to patriarchal values in Egypt, where the elder brother is a leading family figure next to the father.

Portraying his alter-ego, Andeel speaks as though he is all-knowing, dismissing the public's arguments about the state of Egyptian society with his own, seemingly pro-state counter-arguments. He offers alternative solutions to problems plaguing Egypt, including its education system.

The Egyptian regime, which has tens of thousands of political prisoners, seems keen on shutting down all voices that sing to a different tune than that of the government

As noted earlier, the Egyptian state doesn't appreciate Egyptians' sense of humour. The case of Bassem Youssef is among the most notorious. As a result of his political satire TV show, Al Bernameg, Youssef has effectively been barred from returning to Egypt, where he would face prison time and a fine of about $3mn (50mn EGP).

Others have faced even worse repercussions. In late 2015, Amr Nohan was sentenced to three years in jail after being tried by a military court for sharing satirical content on Facebook. Nohan, who had Photoshopped Mickey Mouse ears onto a picture of Sisi and posted anti-establishment comments on his Facebook profile – in addition to complaining about the army in private conversations monitored by military intelligence - was deemed to have "thoughts inside of him that run contrary to that of the ruling regime".

The future of political satire

On the fifth anniversary of the 25 January 2011 Egyptian revolution, comedian Shady Abu Zaid and actor Ahmed Malek decided to celebrate in what was seen as a very unorthodox manner. The duo opted to prank Egyptian police staff by handing out inflated condoms as balloons printed with the words: "From the youth of Egypt to the police on Jan 25."

In a video of the prank, Abu Zaid and Malek pretend to celebrate with pro-regime crowds in Tahrir Square, kissing officers, posing for photos with them, and handing out the inflated condom balloons.

As a result of their viral video, a criminal investigation was launched, Malek's membership of the actors' syndicate was temporarily suspended, and both faced severe social criticism for touching "the untouchables".

And late last year, Eslam El Refaei was arrested for joining an illegal "terrorist" group. Known in the Egyptian tech industry and more famous for his lewd sense of humour on social media, mainly Twitter and Facebook, where his profile was shut down by his friends, Refaei has no involvement in Egyptian politics.

His arrest shocked many, debunking the notion that you're safe if you stay away from politics. It seems the only way to stay safe these days is to be quiet, or "put a shoe in your mouth," as per Egyptian lingo.

The Egyptian government, which has tens of thousands of political prisoners, seems keen on shutting down all voices that sing to a different tune to that of the government.

Egyptian authorities seem more interested in cracking down on political dissent than on fighting deadly armed groups. Sisi seems more keen on pleasing his foreign counterparts through lavish military spending than on pleasing his fellow Egyptians.

Political satire will always be active in Egypt, where citizens will always find a way to express their resentment over the state of the country. Egyptian authorities must realise that controlling the public space is impossible, and treating younger generations as adversaries is a recipe for failure.

Satire will remain a thorn in the side of the government for a long time to come, as tweets, posts, memes and videos usher in a new era of political involvement.

The writer's name is withheld for security reasons. He is a young Egyptian who took part in the 25 January popular uprising and was politically active until the military coup in 2013. He lives in Cairo.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Egyptian President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi has undertaken a series of controversial economic reforms (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye french edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].