Syria war: Bashar al-Assad's long, bloody road to Eastern Ghouta

The brutality of the campaign by the Syrian government forces and Russia in Eastern Ghouta naturally begs the question of what their end game is.

The answer has to do with Eastern Ghouta's strategic location, the government's and Russia's long-term goals for demographic change in Syria, and the future of rebel groups in the area.

What is as important as the end game is examining how the Syrian government and Russia are trying to get there and the implications.

Blocking humanitarian aid

The ongoing escalation of attacks on Eastern Ghouta is proving to be one of the bloodiest episodes of the Syrian conflict. At least 800 civilians have been killed in the area in two weeks, while almost 400,000 residents are living under heavy bombardment, after having been subjected to nearly five years of siege.

Over those years, and in addition to ongoing attacks using conventional weapons, the area has witnessed multiple chemical weapons attacks that the Syrian government and Russia persistently frame as being orchestrated by rebel groups, when all evidence emerging from the ground points the finger at the government and its allies.

The government has constantly blocked humanitarian aid from reaching Eastern Ghouta, leaving its residents with severe shortages of vital goods. Even after the recent Russian announcement that there would be a daily five-hour window of reduction in violence to allow aid to enter Eastern Ghouta, the situation remains bleak.

Humanitarian agencies have said that it takes longer than five hours to get aid convoys to Eastern Ghouta, and despite the announced five-hour window, bombardment has continued, making aid convoys vulnerable to attack as well.Even the so-called "humanitarian corridors" that Russia has announced to allow civilians to evacuate the area - in reality, forced displacement - have remained empty amid continuing bombardment. Aerial photographs of Eastern Ghouta show large-scale physical destruction, in addition to the ongoing humanitarian catastrophe.

Aiming to make Eastern Ghouta uninhabitable is also underscored by the series of chemical attacks on the area - deliberate attempts to make local residents feel that they have no choice but to flee

Many are making parallels between the current campaign in Eastern Ghouta and the one that both the government and Russia conducted in East Aleppo at the end of 2016. There are definite similarities between these and other cases: a strategy of besiegement and starvation followed by heavy bombardment.

But the number of residents in Eastern Ghouta is twice that of East Aleppo before the 2016 campaign, which underscores the scale of the disaster in Eastern Ghouta today.

A deliberately heavy price

The heavy price that Eastern Ghouta is paying is not accidental. The government and its allies have a vested interest in emptying the area of its original residents and making this demographic change permanent.

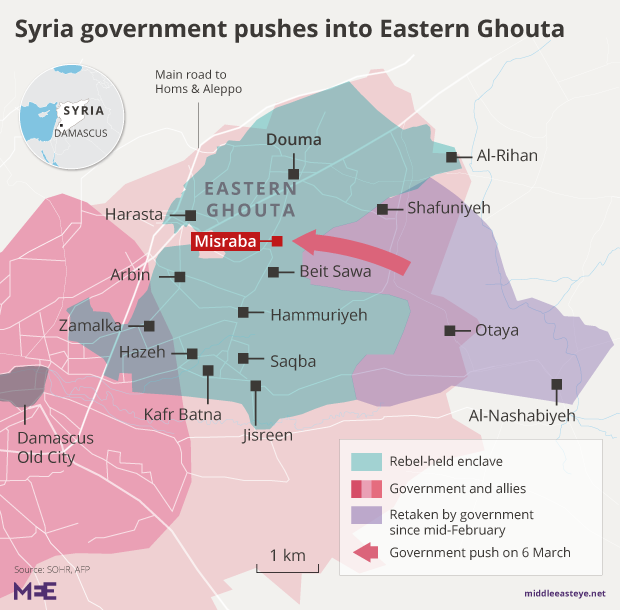

Eastern Ghouta is near the outskirts of Damascus, which continues to be a government stronghold. It is in the interests of the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to spread its military control around areas it currently holds, to expand its scope of influence in key strategic locations and therefore keep its strongholds secure.

The government followed a similar strategy in Daraya in southern Syria. The area is now mostly rubble, and few of its original residents remain. If Eastern Ghouta similarly becomes uninhabitable, this will make it much easier for the regime to control it, despite the government's reduced capacity.

Aiming to make Eastern Ghouta uninhabitable is also underscored by the series of chemical attacks on the area - deliberate attempts to make local residents feel that they have no choice but to flee. However, unlike East Aleppo, where many residents before the 2016 campaign were internally displaced from other areas of Syria or had moved to Aleppo from other regions, the majority of Eastern Ghouta's residents are native to the area and have nowhere to go.

Their resilience is pushing the regime and Russia to escalate their violence to force them to leave.

Surrender would mean extinction

The Syrian government and Russia continue to argue that their campaign is aimed at eradicating "terrorist" groups such as Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, Jaysh al-Islam and Faylaq al-Rahman. The BBC's Newsnight programme two weeks ago tried to explain the situation in Eastern Ghouta as being about the regime attempting to turn local residents against these armed groups and pushing their fighters to be evacuated to elsewhere in Syria.

However, the residents of Eastern Ghouta are for the most part caught in the fighting, without having much sway over any of the rebel groups. Additionally, the campaign by the regime and Russia is targeting districts in Eastern Ghouta that do not have much presence for Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, whose fighters there are estimated to number between 150 and 200.

As for Jaysh al-Islam and Faylaq al-Rahman, these two groups had in the past clashed with one another, but they are currently coordinating on the ground as they face a common enemy.

The two groups recognise that surrendering in this battle would mean extinction, and therefore will fight until the very end to prove their credibility. Ironically, then, instead of weakening the groups, the campaign by the regime and Russia is strengthening their pragmatic collaboration.

The Syrian government's end game in Ghouta is difficult and extremely bloody. Whether it reaches its goal or not, the damage caused by the journey will be extensive.

- Lina Khatib is the head of the Middle East and North Africa Programme at Chatham House. You can follow her on Twitter @LinaKhatibUK.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Syrian government soldiers walk down a street in the town of Al-Mohammadiyeh, east of the capital Damascus, on 7 March 2018, as Syrian government forces push into the rebel-held eastern Ghouta enclave (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].