Of war and other demons: Tehran's anti-war exhibition

TEHRAN - Ali Akbar Sadeghi was only eight years old when his five-year-old brother, Ali Asghar, was diagnosed with typhoid fever, which spread through contaminated water and food in 1940s Iran.

“Ali Asghar lost a lot of weight, he was nothing but skin and bones,” Ali Akbar recalls. “Eventually he died. For years, my mother kept a piece of his clothing, and from time to time she smelled it."

Sadeghi says that his younger brother's early death made him appreciate every moment of life. “That’s why I deeply suffer when I see images of current wars and bloodshed. I suffer because I appreciate the beauty of life.”

I deeply suffer when I see images of current wars and bloodshed

- Ali Akbar Sadeghi

While power struggles are convulsing the Middle East, at a time when the drumbeats of war with Iran are getting louder, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art (TMOCA) launched a large exhibition of Sadeghi's works.

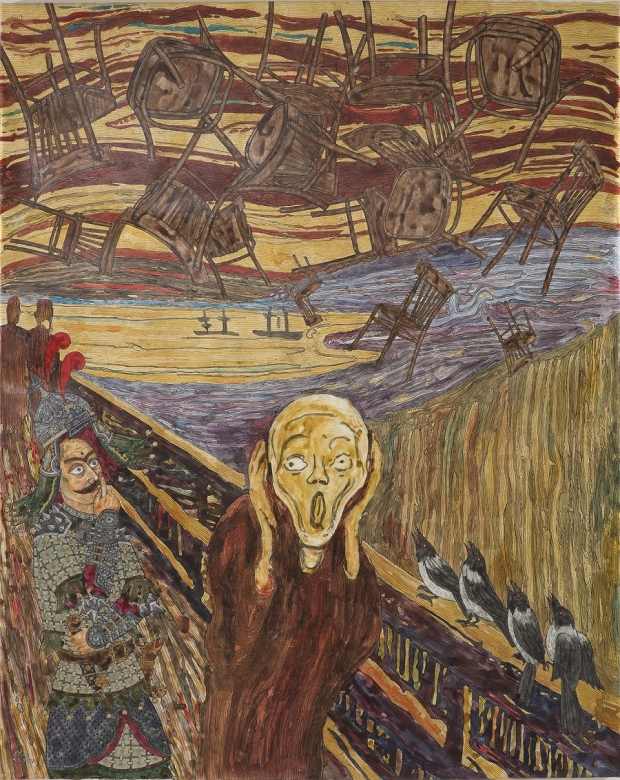

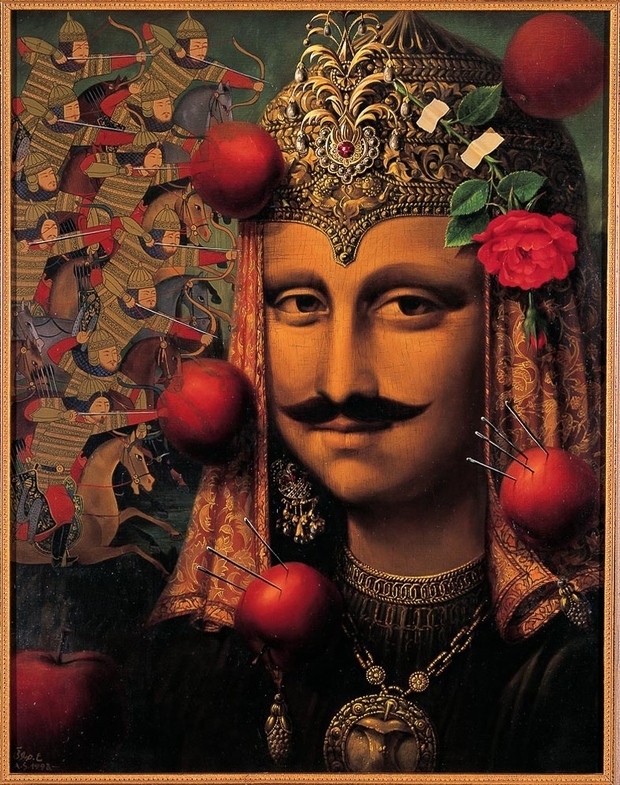

Since the 1970s, Sadeghi has been a key figure in the Iranian art scene. Having developed a unique painting style that combines symbolism, surrealism, Iranian teahouse painting techniques and Persian miniatures, he has won several international prizes for his animated movies and book illustrations.

Unending wars

Since the beginning of his career, war and conflict have always been at the centre of Sadeghi’s artwork. Even during the 1970s, when US President Jimmy Carter dubbed Iran “an island of stability,” Sadeghi was creating anti-war animation movies.

Flower Storm, The Rook, and Seven Cities were his three award-winning animation movies condemning war-mongering world leaders. War is a global concept for Sadeghi, as old as life itself and not limited to a specific time.

This complex view of good and evil is clearly depicted in Sadeghi’s most recent series of paintings entitled Demons. Painted with intense colours, his demons seem deeply human. In some paintings they look overjoyed, while in others they seem melancholic. In one piece of artwork, his demons are bound in chains and appear like they are being tortured.

“But today’s fights are different. Nowadays, we see that young men and women explode themselves with bombs attached to their bodies.”

Pawns of war

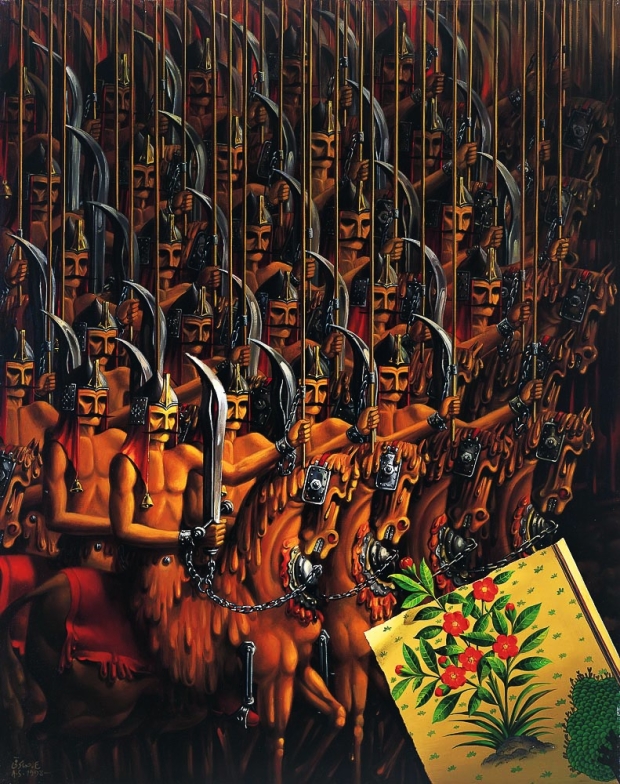

Sadeghi’s work not only focuses on civilian casualties and the ongoing humanitarian crises in the region, but also brings the ordinary soldiers being manipulated by the world's superpowers to the attention of his audience.

“Ali Akbar Sadeghi’s paintings are filled with warriors who hide their faces from the viewer’s gaze,” wrote Iranian art critic Amir Nasri in a Farsi article entitled The Hidden Face, published by the Ali Akbar Sadeghi Foundation in a catalogue about the artist’s work.

“A disguised face is one that lacks individual characteristics. It is a face that can belong to a group of people and not only one individual,” Nasri adds.

“I quite often think of soldiers, and of what’s going on in their minds,” Sadeghi emphasises. “I keep asking myself what would happen if soldiers understood how they are being abused by the warlords.”

Nails

Although Sadeghi pities the soldiers who participate in wars, he does not forgive them for the bloodshed they have caused. In a series of paintings, nails are hammered into the faces of the soldiers portrayed.

In Sadeghi’s paintings, you can see a blend of rebellion and serenity

- Naser Fakouhi, anthropologist

“In Sadeghi’s paintings, you can see a blend of rebellion and serenity,” explains Naser Fakouhi, an Iranian anthropologist and the president of Iran’s Anthropology and Culture Institute. “And these nailed portraits are one of the best examples of an artists’ calm rebellion.”

Fakouhi, who conducted hours of lengthy interviews with Sadeghi as a part of the “Cultural History of Modern Iran” research project, discovered that the Nails series was inspired by Sadeghi's childhood.

For a while, his job was to straighten crooked nails, and that was when he developed a love relationship with the nail

- Naser Fakouhi, an Iranian anthropologist

“For a while, his job was to straighten crooked nails, and that was when he developed a love relationship with the nail,” Fakouhi laughs. “A crooked nail is 'nothing' because it is useless. But when he straightened the nail, he transformed 'nothing' to 'a thing' which became a useful nail.”

Decades later, these nails appeared in Sadeghi’s paintings, installations and sculptures. In 2008, with pieces of wood and nails, he created several pots of cacti. At a retrospective of his work, two chairs are also displayed which are covered in nails.

“Several layers are distinguishable in Sadeghi’s artworks,” explains Fereshte Moosavi, an Iranian artist and a PhD candidate in the curatorial programme at Goldsmiths, University of London.

“Various components in his paintings declare that his art is not restricted only to his personal emotions and thoughts. Sadeghi illustrates the concerns of contemporary society, and awakens our collective consciousness.”

“Artists might not be able to change the world,” Sadeghi concludes. “But I want to make my audience think. I want them to think of what’s going on around them in the world, and of what they do as human beings.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].