Freedom and censorship collide at Beirut Cinema Platform

BEIRUT - “Beirut is where dreaming is still possible,” Beirut Cinema Platform (BCP) director Jad Abi-Khalil said.

BCP – which ran from 22-25 March – is the latest film industry platform to emerge from the turbulent political climate engulfing the region. It's an initiative capitalising on Lebanon’s political neutrality, its strong European connection, and the relative freedoms it enjoys.

“The political, religious or sexual restrictions found in most Arab countries are absent in Beirut," Abi-Khalil told Middle East Eye. "Forget about the state, forget about censorship – Beirut is the one Arab country where you can live whichever you want, and this freedom is manifested in the movies developed at the Beirut industry platforms.”

Major shakeups and alarm bells

Its success has given industrials and critics alike plenty of reasons to be optimistic about the future of Arab filmmaking, yet the tightening censorship, manifested in glaring interference for the second year in a row, has, at the same time, rang more alarm bells over the diminishing freedom of expression across the region.

In the absence of state funding in most of the Arab world, co-production platforms have become fundamental for Arab filmmaking.

We want to foster Arab productions

- Jad Abi-Khalil, festival director

They are a space for acquiring funding opportunities via regional and European producers, networking with film programmers and distributors, and winning monetary or service awards.

In the past few years, the regional film industry has experienced major shakeups: the discontinuation of the Abu Dhabi Film Festival with its lavish monetary prizes and the subsequent closure of its Sanad grants; the termination of the Screen Institute Beirut fund and the downscaling of the Dubai Film Festival due to budget cuts.

Additionally, the Gulf crisis means that filmmakers from the UAE, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain no longer have access to grants from the Doha Film Institute, which is the most consistent and robust funding body in the region. Meanwhile, Qatari filmmakers are unofficially shunned from programmes engineered by Dubai and Egypt’s new luxury festival, El Gouna Film Festival.

Fostering Arab productions

BCP has thus emerged as an impartial alternative to the far richer and more established fairs in the region. The brainchild of Beirut DC, a non-profit association organising workshops and exhibitions of Arab films, BCP was the industry link missing from DC.

The political, religious or sexual restrictions found in most Arab countries are absent in Beirut

- Jad Abi-Khalil, director

Fondation Liban Cinema, which aims to support the development of the Lebanese film industry, was the first partner BCP acquired in its inception in 2015, and before long, more partners such as the Beirut Locarno Academy joined the platform. Fifteen projects are picked up every year, with one key precondition: both directors and main producers must be Arabs.

“We want to foster Arab productions,” Abi-Khalil said. “Projects already attached to foreign producers have bigger chances of getting financed, that’s why we’re requiring the involvement of Arab producers.”

The projects compete for a multitude of awards: colour grading services; sound mixing services; workshop grants; participation in film festivals, and monetary awards for films in development.

The outcome of BCP’s first two festivals speaks for its great efficiency: five co-production contracts have been signed and 70 percent of the participating movies have been completed.

A large proportion of these films ended up going to various major film festivals, including Kaouther Ben Hania’s Beauty and the Dogs (Cannes), Ziad Kalthoum’s Taste of Cement (Visions du Réel), and Rana Eid’s Panoptic (Locarno).

Ambitious expansion plans for the BCP are in the pipeline. “We want to cover all production stages in the platform, from development to distribution,” Abi-Khalil said. “I’d love to start a shorts section for filmmakers under 30. We want to include younger generations in the platform.”

No preconditions

El Gouna Film Festival aside, most film initiatives in the region are funded by their respective states, which naturally informs the politics of the chosen films, directly or indirectly, even in liberal countries like Tunisia.

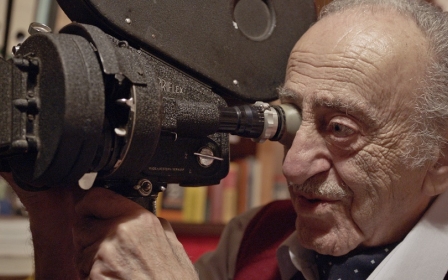

BCP is a purely private endeavour, managed by some of Lebanon’s most respected film figures, including documentary filmmaker Elaine El Raheb and film programmer Zeina Sfeir, which gives it the kind of independence many entities in the region lack.

“State funding, even in a place like Tunisia (where there are typically fewer restrictions), comes with plenty of preconditions,” Abi-Khalil said. “We, however, don’t have that. We don’t have any restrictions. Our only criterion for choosing films is quality, that’s all.”

Censorship worsening

The positive buzz the BCP has generated during its young life was offset by continuous interventions by Lebanese censorship. For the second year in a row, films at BCP’s sister programme, Beirut Cinema Days, were hampered by bizarre censorship demands.

Last year, the government’s censorship bureau, a branch affiliated with the General Security, insisted on the excising of 12 minutes from Magdi Ahmed Ali’s Egyptian commercial smash Mawlana (The Preacher), a mainstream soap opera exploring the relationship between the authorities and corrupt religious institutes. The film also tackles the taboo Shia presence in Egypt.The same year, the government censorship bureau was to blame for not granting screening permission for Roy Dib’s Lebanese production The Beach House, a multi-character chamber drama with gay themes at the heart of the story.

The general atmosphere in the Arab World is not great; in Syria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar...we certainly get affected by the conflicts around us

- Jad Abi-Khalil, director

This year, there was one substantial cut in Rana Eid’s Panoptic, a documentary that touches upon the security apparatus and secret detention centres for foreigners in Lebanon. Refusing to yield to censorship demands, Eid failed to acquire censorship approval and put the film online instead.

Even more outlandish was the initial qualms expressed by Lebanese censorship towards Palestinian director Annemarie Jacir’s Nazareth-set feature, Wajib.

A scene where the leading character gives the middle finger to the Greek Orthodox Church (for selling Palestinian properties to Israel) was reportedly deemed objectionable, therefore screening permission was not given until the last minute, when officials caved in to public outcry.

Many creators believe that censorship is getting worse in Lebanon, yet Abi-Khalil believes it’s nothing new. “Things have always been bad. Every edition of Beirut Cinema Days had problems with the censorship. Every event in general always bumps into problems with the censorship," he said.

“The general atmosphere in the Arab world is not great; in Syria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar...we certainly get affected by the conflicts around us."

“The problem is twofold. On one hand, the 50-year-old censorship law is senseless and backward-looking. We’ve [been] working on a new law, which transfers censorship from the hands of the General Security to the Ministry of Culture. We hope to get it approved in the next parliamentary elections in May,” he added, referring to the 1947 law.

The General Security’s role as a censorship authority, which is under the interior ministry, is in breach of the current law stipulating the formation of a censorship committee comprising representatives from several ministries, as well as the General Security.

Sectarian considerations and political taboos play a role in the General Security’s decision-making as well.

Abi-Khalil says that Lebanese censorship is shaped by individual censors or ministers with no tangible agendas. Their decisions are akin to mood swings, erratic and unpredictable.

“We’re controlled by several dictators, each of whom has full control over his sect; each of whom is hell-bent on protecting the interest of his group,” Abi-Khalil said.

“That’s why we do not have clear-cut taboos or guidelines. I don’t think there is any firm decision-making in preventing or allowing films from screening. What we have here is nothing but stupidity.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].