Will Erdogan do a deal with Assad to end Syria standoff?

Turkey and the ruling AK Party’s whole Arab policy that launched in 2003 was built around the personal relationship between President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Of course, circumstances led to a complete reversal of this relationship, as the two leaders became bitter rivals in a conflict that has torn Syria apart. One could argue that no outside country has the ability to end the war in Syria as much as Turkey. In turn, it must be said that only Erdogan can end it, as the whole of Turkey’s Syria policy revolves around Erdogan.

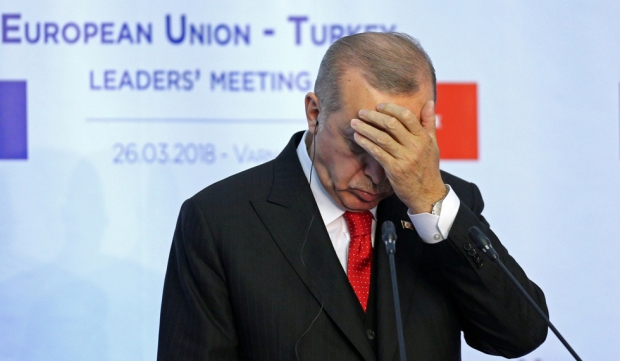

It is he alone who decides what happens next. Despite the recent takeover of Afrin - in what can be described as a victory by the Turkish military, rather than by the Free Syrian Army - Erdogan finds himself increasingly isolated, and the takeover of Afrin could come back to haunt him.

Assad may well be the ultimate winner in Afrin - and with increased domestic Turkish pressure to talk with Damascus, what would finally force Erdogan to do so? And in any event, would Damascus be interested in speaking with Ankara?

A brotherhood blossoms

In 2005, Erdogan orchestrated a visit by Turkish President Ahmet Sezer to meet Assad. At a time when much of the global community looked to Turkey as the model example for democracy in the Middle East, many Syrian opposition groups were appalled that Erdogan was making such strong overtures to Syria, in direct contrast with the stated aims of Turkish support for democracy in the Arab world.

A leading critic of Damascus, Farid Ghadry wrote that while the EU and the United States were censuring Assad for Syria’s role in Lebanon and Iraq, Erdogan was cementing his relationship with Assad and using Syrian influence with the Arab League to improve ties with Egypt, Libya, Algeria and Qatar.

For Assad, a rapprochement with Erdogan means Turkey needs to drop its support for radical Islamist groups in Syria

At the height of Erdogan’s love affair with Assad, the Turkish leader called him his dearest and closest brother, and they enjoyed at least three holidays together with their wives and in-laws. Abdullah Gul also got caught up in the act of hosting the Assad family on the Bosphorus.

The Turkish political elite was falling head over heels for the Syrian president. A free-trade agreement was followed up by a visa-free zone, and Turkish businesses flourished all over Syria. The biggest beneficiary of the Assad-Erdogan relationship was the beleaguered Turkish military and intelligence services, which had fought an unsuccessful decades-long war against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Assad reversed his father’s policy of supporting Kurdish groups, as well as the multiple Marxist, Armenian and leftist groups fighting the Turkish state since its 1923 foundation. The success of Erdogan’s peace treaty with the PKK depended overwhelmingly on Damascus, and the regional influence Assad and his intelligence apparatus could exert to bring various anti-Ankara groups to the table.

Arab policy in tatters

In post-Saddam Iraq, when Turkey was confused over its alliance with the US, Damascus brought its own tribal connections to the Sunni heartland, so the Turks could establish relationships lost since Ataturk cut off Turkey from its southern flank.

Now, a decade since the famous Bodrum holiday of Assad and Erdogan, Turkey’s Arab policy is in tatters. The UAE, Egypt, Algeria and Saudi Arabia all oppose Turkey’s involvement in Arab affairs. Major Arab states have criticised Turkey’s offensive in Afrin and northern Syria as a blatant violation of Arab territory. The Saudi crown prince and the UAE leadership have become unlikely allies of Damascus in accusing Turkey of bringing back Ottoman expansionist policies.

Erdogan’s Kurdish policy has fallen on its head, and Damascus is now fully behind all the forces that had brought Turkey and Syria to near-war in the 1980s. The Afrin operation has been criticised by almost all of Turkey’s Nato allies and has pushed the Syrian Kurds firmly into the lap of Assad.

Syrian Kurds do not trust the United States either, as they feel that after doing the bulk of the fighting against the Islamic State, they have been fed to the wolves as part of a great power game. The Orthodox block of Armenia, Serbia and Russia are firmly in Assad’s camp, and with Chechen President Ramzan Kadyrov also supporting Damascus, Erdogan’s dream of a neo-Ottoman alliance is falling apart fast.

On top of that, there is no sign of any rapprochement between Cairo and Ankara, and Assad has taken full advantage of this by including Egyptian military intelligence in the recent ceasefires and reconciliation agreements in various parts of Syria.

The public spat between the UAE and Turkey over interference in Arab affairs, and Assad’s own relationships with the UAE and Oman, have meant that Erdogan can no longer use the Arab Sunni card against Damascus. Indeed, Egypt has called for Syria’s return to the Arab League.

Syria’s history of defence diplomacy

Erdogan has also faced a lot of pressure from within Turkey over his Syria and Kurdish policy. The pro-AKP daily Yeni Safak has openly called for a dialogue with the Syrian government.

At the same time, the head of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) has called for an immediate conversation with Assad, noting he is ready to travel to Damascus to do so.

Erdogan’s opponents say he has brought Turkey to permanent war with its own Kurds and Syria. At the same time, his embrace of Syrian-Kurdish leader Salih Muslim several years ago proves that Erdogan keeps flip-flopping over his allies in Syria.

Despite Iran’s and Russia’s close working relationships with Erdogan, they are unlikely to back him over Assad – which means that with an increasingly hostile West, Erdogan has no option but to give into Russian President Vladimir Putin and Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

So, will Erdogan reach out to Assad? Last year, he hinted at collaboration with Damascus against the Syrian Kurds, but this year, Erdogan called Assad a terrorist.

Beyond the headlines, a deal with Assad is far more realistic than any accommodation with PKK affiliates and Marxist groups, which are way beyond Erdogan’s reach. With the very public financial and diplomatic support of Assad from India and China, the BRICS bloc is also against Turkish aggression in Syria.

The more important question is: will Damascus talk to Turkey? The Syrian history of defence diplomacy is all about pragmatism and surviving crises. Syria supported the US war against Iraq in 1991, yet supported Saddam-era Baathists post-2003. Assad supported Iran in Lebanon, yet opposed Iranian proxies in Iraq.

For Assad, a rapprochement with Erdogan means Turkey needs to drop its support for radical Islamist groups in Syria. With increased tensions in Turkey’s own domestic demographics and upcoming elections, Erdogan must focus on domestic unity rather than Ottoman ambitions for Syria.

This story still has a long way to go, but for the moment, Assad is sitting comfortably, having weathered the worst storm.

- Kamal Alam is a Visiting Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). He specialises in contemporary military history of the Arab world and Pakistan, he is a Fellow for Syrian Affairs at The Institute for Statecraft, and is a visiting lecturer at several military staff colleges across the Middle East, Pakistan and the UK.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (R) shakes hands with Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan during a meeting in Aleppo on 6 February 2011 (SANA)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].