The 10 most important ways to counter Europe's anti-Muslim narratives

The UK is "anything but Islamophobic", so spoke a Muslim organisation head in a comment to the press on the Islamophobia Awards in 2004. Because, he added, Britain has such a vibrant anti-war movement.

The awards – a satirical revue and fundraiser inspired by Amnesty International's Secret Policeman's Ball - were described that year by the then head of the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) as an important step to "fight bigotry and prejudice against Muslims". Both the Muslim organisation head and CRE head have now swapped positions, but this tale is instructive because of the more than one elephant in the room when talking about Islamophobia.

These "elephants" provide the backdrop to the latest report on the UK for the Counter-Islamophobia Toolkit project led by the University of Leeds. The report and those of the seven other countries in the project lists the 10 main counter-narratives (in each state) to Islamophobia being deployed or demanded by those concerned with addressing racism.

The 10 narratives come out of desk research but mainly interviews with over 180 activists, academics, journalists, politicians, religious figures and other actors across the UK, France, Germany, Belgium, Greece, Czech Republic, Portugal and Hungary.

They are summarised here. A few will be referred to below in overviewing the recommendations to civil society, institutions and the state that the report has produced. Specifically, understanding the nature of the problem we face when it comes to anti-Muslim hatred, and then how to counter it, who should counter it and indeed why we (any of us) should.

1. What's the problem?

It seems an obvious answer. It's Islamophobia. However understanding the problem - and indeed admitting that there is one - is the first issue that needs to be dealt with. It is not simply a case of getting the state to recognise Islamophobia – something that is now being acknowledged (albeit grudgingly) as a street-level phenomenon.

Civil society, including old and new advocates against racism - including Islamophobia - need to be able to see Islamophobia as part of the nexus of institutional injustices that deny - in this case - Muslims, or those perceived to be Muslim, the ability to project themselves into the future (see Brian Klug and Salman Sayyid on what this means, and how it is a reproduction of the function of anti-Semitism).

Islamophobia in political media discourse and representation, in curricula, in the enacting and operation of laws and policies are in this analysis the cause of Islamophobia

So claiming that the UK is not Islamophobic because there is a street/civil society mobilisation against war (which is indeed an indicator of anti-racist mobilisation in part) actually misses the fact that the wars in and of themselves were racist wars, and were justified through the use of racist and Islamophobic tropes and social undercurrents.

Likewise the acknowledging only of street-level harassment and violence gives undue credence to the idea (in the UK particularly) of the post-racial society. Islamophobia in political media discourse and representation, in curricula, in the enacting and operation of laws and policies are in this analysis the cause of Islamophobia.

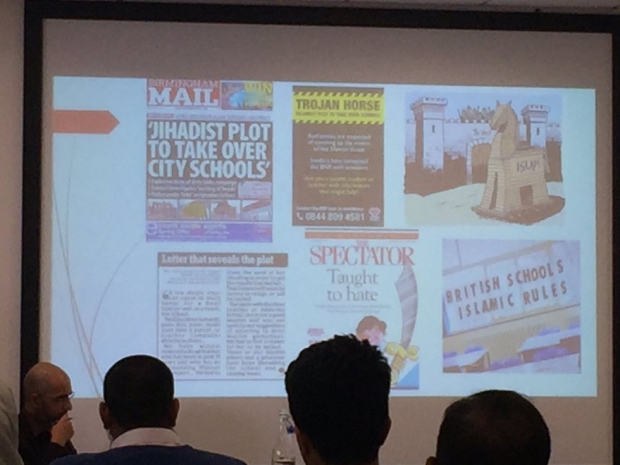

2. The Islamophobic media

It's not as obvious as it should be. On a panel some years back on the UK, I sat with two academics and Malia Bouattia (then the National Union of Students black students officer) making this point. A further panelist, a volunteer from one of the later established anti-Islamophobia organisations – a truly genuine and dedicated sister – explained Islamophobia from the organisation's script.

This is no small feat when the daily barrage of inaccuracies against Muslim individuals has reached truly insidious proportions. As the failed complaint against Trevor Kavanagh's piece against Channel 4 anchor Fatima Manji's wearing of the hijab proved however, the institutions that regulate the press are at best limited and worst unable or unwilling to deal with the media's institutional biases.

The media needs to be able to transform its general culture whereby it understands the structural and pervasive problem of Islamophobia in its representation (including its lack of representation) of Muslims

Even at the level of the individual, these institutions were unable to protect a new anchor's religious expression in the form of her dress choices being lambasted with calls for her to be removed from her role for choosing that.

The media needs to be able to transform its general culture whereby it understands the structural and pervasive problem of Islamophobia in its representation (including its lack of representation) of Muslims. There has been an upsurge of agenda-led right-wing voices being platformed across the media.

Addressing the myths of "balance", often used to justify this, is, therefore, needed not because it incites some predisposed right-wing people "out there" to commit violent acts of hate, but because it helps to create an environment of hate wherein Muslims, but also other subalternised people, are insidiously cast out from the norms of society.

Because Muslims are characterised as intrinsically inimical to the values and norms of society, they are not able to exercise any type of effective citizenship. Thus a group of parents, teachers and school governors turning around the fortunes of failing schools, and raising the educational achievements of children in the lowest social strata of British society into the top 14 percent of achievers in the country can be characterised as signs of an extremist takeover, rather than something that concerned parents and governors across the country have been doing for decades.

3. Exercising citizenship: The 'Trojan Horse affair'

This is of course the Trojan Horse, or more properly, the Hoax Affair.

Because of the mutually supporting and reinforcing positions of media, government, the law and their various institutions, the impact of something like Trojan Horse is not limited to one issue but has state and society-wide ramifications – aside from the ongoing demonisation of Muslims, it directly forms the basis upon which a counter-extremism strategy replete with new laws and policies is based.

Indirectly however it becomes a justification in perpetuity, of the nefarious nature of Muslims, around which institutional conversations and praxes are based.

Maybe an example brings this impact to light. Upon being elected president of the University of Salford's student union and a national executive councillor of the NUS, Zamzam Ibrahim found her tweets, made five years previously when she had just turned 16, being published in the mainstream media with claims made as a result that she was an anti-white racist and an extremist.

Finding herself forced to explain herself (repeatedly) Ibrahim was also subjected to 48 hours of threats, including rape threats and abuse via social media. She wrote after the event of the right-wing media that:

"They often paint us as caricatures undeserving of empathy or understanding. They want to deny our humanity because they want you to be afraid of us. We cannot allow this situation and allow this cycle to continue in Britain today. Because the first step of solving any problem is admitting there is one."

This works for civil society too. The nature, style and content of counter-narratives to Islamophobia can and should vary, but understanding the problem and being willing to admit it are crucial if there is to be any successful push back against it.

4. The how and the who to counter Islamophobia

The 10 narratives in each country vary, but many are cross-cutting and point towards a globalisation of anti-Muslim narratives. Thus countries with very few Muslims, eg Czech Republic and Hungary, not only have similar narratives of anti-Muslim hatred around intrinsic terrorism, the subjugation of women and so on.

This can manifest in the reporting of any car accident as maybe a terrorist incident, despite there being so few Muslims and no history of political violence by Muslims in the country.

As Zsuzsanna Vidra highlights in her report on Hungary, Islamophobic tropes on Muslims, Islam and security are easily collapsible into issues around immigration, and indeed a consultation on both immigration and terrorism can be launched without ever explicitly mentioning Muslims and Islam.

Because Muslims are characterised as intrinsically inimical to the values and norms of society, they are not able to exercise any type of effective citizenship

Nevertheless,"the prime minister and his government as well as the media close to them, made the 'migrant - Islam - terrorist nexus' the dominant discourse. Thus, security linked to (Muslim) terrorism has become the official political narrative thus prescribing how the migration/refugee crisis should be interpreted. Nonetheless, as pointed out, in the political communication of the government, the 'anti-migrant' narratives do not always make direct reference to Muslims: neither in the national consultation on immigration and terrorism, the billboard campaigns nor in the referendum questions is there an explicit mention of Muslims or Islam."

5. Humanisation of Muslims

Counter-intuitively however, respondents in the UK were wary about the project of humanisation of Muslims as a counter to their demonisation and dehumanisation by the processes of Islamophobia. Why? As post-doctoral researcher Kasia Narkowicz laments,"'I condemn, I condemn', I just don't think that’s a good counter-narrative. A good counter-narrative is to challenge the narrative on which the questions are based and this is happening but in activists' space…".

Poet Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan is more scathing in her award-winning spoken word piece: "This is not a humanising poem" (2017). She decodes the conditionality placed on Muslim presence and acceptance.

Love is when you are not an athlete

or bake cakes

Love is not when we offer our homes

or free taxi rides after the event.

In other words, the national conversation and the national story needs to include Muslims regardless and without conditions. She concludes: "If you need me to prove my humanity/I'm not the one who's not human."

The proliferation of projects aiming to normalise Muslim presence eg those highlighting the role of Muslims in the armed forces during the first and second world wars, as with condemnations of terrorist acts, are responses to a narrative of Islamophobia that simply emphasises the connection that they seek to sever.

Instead many interviewees point to the needs for Muslim space wherein Muslims can control their own narratives. This space is continually under attack, and shrinks year on year. The farce surrounding the National Youth Theatre's pulling of the play by Muslim artists, Homegrown, whilst the National Theatre lauded a production on similar themes by white playwrights, highlights this.

6. The deep social crisis

The institutional backlash against Homegrown (before being cancelled, police were sent to view rehearsals and review the script) speaks to the situation that the majority of interviewees have expressed, described as an understanding of Islamophobia as an undermining of the ability of Muslims as Muslims to project themselves into the future.

In this scenario, Muslims are not only denied the ability to define Muslimness in any of its diversity but also are defined by state and institutional discourse and praxis that is a form of violence against them. It disempowers them from having any role in the development of wider society.

Arun Kundnani, interviewed for this project, stated:

"Islamophobia is ultimately a symptom of bigger, wider, deeper issues in British society. Islamophobia is not just ever about Muslims, it's about a deep social crisis. But the experience of Islamophobia is also particular to Muslims and has its own particular feel and texture and history and experience and so forth, and so, the challenge in taking it on is to both enable a space where Muslims can articulate and define their own experience and their own response to Islamophobia in Britain while at the same time being able to link that particular story to the wider crisis that Islamophobia needs to be linked to. And that wider crisis will be to do with the whole structure of British society in the end and therefore implicates everyone in Britain.”

What does that space look like? Creatively (and this was one of the overwhelming recommendations) art, drama, comedy and many other creative forms that speak to Muslim experience, within physical, virtual and psychological space. However the idea that Muslims have the ability and right to speak to something other than their own or a wider "Muslimness" is also crucial to this. Former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan William's contribution included the idea that:

"… Muslim commentators in the media are seen to be addressing other intelligent and resourceful issues not just religious ones . .. that is surely one of the things that would make a difference. This [Muslims] is a set of resources, identities, convictions that can contribute to a general civil discourse, not just one about religion, but about justice, poverty, the environment etc."

A new generation

This is my aside, and not part of the research findings: a plethora of Muslim talent has been dissipated in knee-jerk responses to Islamophobic narratives and practice, when actually they have much to contribute elsewhere.

What else has been critiqued is the failure of Muslim civil society to cohere over Islamophobia. Its own narratives - from kindness to the unkind (admirable amongst the weak but not necessarily in an unequal power relationship), meekness in the hope of kindness, friendship in the hope of acceptance or at least tolerance - undermine the claim of citizenship and equality.

It goes to the heart of how, as civil society, with or without the partnership of the state and institutions, we counter Islamophobia. Back in 2004 Massoud Shadjareh noted the dilemma of civil society that was reproducing conditionality after the Madrid attacks:

"While younger organisations… called on mosques to pray for peace for all in the wake of the horror of Madrid, the Muslim Council of Britain called on mosques to report any suspicions they had about anything. It's the difference between being a part of society, however marginalised, and perpetuating the idea that you are an unruly guest, your stay determined by different conditions than for everyone else. You don't have to be disaffected youth to see the anomalies and feel the isolation."

7. A travesty of justice

For this study, Kundnani spoke about the Trojan Horse moment. A moment in his view, and indeed that of many activists of various backgrounds, where Muslims, regardless of their backgrounds, needed to draw a line in the sand and firstly defend those so wrongly accused, and secondly themselves and all those who, like Muslims, have the potentiality to be oppressed in this way.

Indeed John Holmwood, whose book with Therese O’Toole on Trojan Horse lambasts the injustice of the issue, speaks of the affair as a travesty of justice akin to the Hillsborough disaster in terms of the state and institutional responses and narrative. The feeling on the ground during the affair was much different.

Caught between the suspicions of other Muslims, and a belief that the system that was so viciously demonising them would somehow vindicate them, those targeted individuals didn't really stand a chance. Children from disadvantaged backgrounds who had been given hope and a chance to excel were the collateral damage.

Countering the obsession of law and policy with marks of Muslimness leading to the expulsion of the Muslim subject from equality before and the protection of the law is a repeated theme. But understanding that obsession and its function in wider social and political discourse is essential.

Musthak Ahmed, an immigration and employment discrimination lawyer summed it up as "the obsession of the courts and policymakers with what Muslim women wear rather than operation of Home Office rules that fundamentally violate human rights". At the time he gave his interview, he connected skilfully and powerfully issues such as the poverty, ill health including mental trauma, and homelessness created by the "hostile environment".

8. Post-Brexit hate crime surge - and the need for safe space

The post-Brexit surge in hate crimes against - even and especially against - EU nationals is tied up with the anti-Muslim demonisation of the "Breaking Point" poster, among others, and highlights how Islamophobia has become the vanguard racism that justifies attacks on all "others" to those a little further up the social chain, i.e. the white working class.

The hostile environment may be streamed off in academic, civil society and even activist circles as an issue of immigration, but it inexorably ties in with deprivation, health, counter-extremism and securitisation, and the rise of the "Statsi" state where ordinary citizens police the "others".

Under Prevent, it is for signs of "radicalisation", and under the hostile environment it is for immigration status. When the processes are so similar, the function and the outcomes are inevitably going to be the same.

"Discussions" around first the niqab and now the hijab as problematic symbols of Muslimness (see the ongoing Amanda Spielman and Ofsted affair) need to be tackled but, again, to do so requires more than just responding in the terms of the attack. When prejudice is so firmly established as the lens through which the prevailing culture views others, then simply "showing the truth of the matter" will not succeed.

No amount of participation in civic life by hijab or niqab clad women (and there has been a mighty upsurge over many years), or the rise in modest fashion etc, has diminished anti-Muslim narratives using these tropes. This is how institutional and societal racism works.

Whilst this narrative is iniquitous on its own, it and other obsessions with Muslimness ("conservative" religious practices and views like support for Palestine etc) masks the much wider and unending crises of the countries we live in, be they economic, social or other.

This retelling is in fact the antidote to nativist myths born from a long colonial history that haunts the relationships between people in the UK. When the understanding of the interconnectedness of being between peoples is understood at a societal level, progress can be made. For their part, activists of whatever ilk are contributing to this, but what of the partners needed?

9. Accountability for state and institutional racism

This is the last elephant in the room. Accountability as an issue exists in the context where the state feels it can withhold the rights and therefore its obligations to citizens/humans because of their perceived behaviour/abnormality/lack of humanity. How many examples can we give?

Deportations of Windrush citizens, the Trojan Horse affair, the maligning of great swathes of Muslim civil society, the disproportionate sanctioning of lawyers from the black asian minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds, the list is endless.

Once upon a time we had judicial inquiries leading to landmark reports like Scarman. Now where enquiries exist as Trojan Horse has shown, they do so with a present agenda and find in that favour regardless of evidence.

What recourse to justice then for those abused? What happens when the law hampers equality? It's not simply enough to have the optics of equality, for example though increased representation at institutional levels by number.

There has to be substantive cultural change. We don't just need more Muslim journalists therefore, we need a media that understands and caters for the Muslim (and all otherised/marginalised) subjects in its entire output.

Does it sound too much? Imagine the resistance to regional accents at the BBC that arises each year and the struggle for presenters not conforming to the BBC voice to be taken seriously, and then multiply that by the many who feel that they are not respected by the media.

Politically, this means movement building, and as last year's UK elections have shown, this can be done in the most unlikely of situations, but it does require sacrifice and struggle. Within this "internal" solidarity, building between disparate Muslim groups and also different regions was highlighted.

10. Muslim autonomy

Using the arts (as discussed) and creating and developing existing alternative art spaces was another recommendation. Likewise, the need to strengthen advocacy and legal support services from within the community and develop more alternative media (in parallel with, but of less significance than, entering mainstream media) were highlighted.

As so many respondents were pessimistic about interacting with the state or established institutions, this remains the overwhelming recommendation. This is the space that is being created and contested by civil society and the grassroots, challenged and attacked by the state and its structures in various national settings.

In this struggle lies the hope that addresses the otherwise pessimistic mood of respondents. Existing and new research has revealed in Westernised nation states the legitimisation of an "environment of hate" which, in the UK setting, has not only trumped internal and external perceptions of the UK as a multicultural state, but has become part of the fabric of a national story of what it means to be British.

Not only is Britishness navigated through a denial of "Muslimness", it is also represented through the articulation of supremacism as a normal facet of law and nation. So much could be said and demanded of the state and its institutions, including the need for brutal self-analysis of their pretensions to "liberal" or "progressive" values.

Read all of them in the reports across the project and the UK here. Waiting for its recommendations to be enacted, however, is not an option. Making another world possible outside of the need to interact with the state is perhaps the only way to go. And indeed many have already voted with their feet.

- Arzu Merali is a writer and researcher based in London. She is one of the co-founders of the Islamic Human Rights Commission (http://www.ihrc.org.uk) and co-authored its recent study Environment of Hate: The New Normal for Muslims in the UK with Saied Reza Ameli. She is currently working on the multi-partner project ‘Counter Islamophobia Toolkit’ with the University of Leeds.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: British Prime Minister Theresa May leaves Finsbury Park Mosque in the Finsbury Park area of north London, on 19 June, 2017, following an vehicle attack on pedestrians nearby (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].