Sisi's regime is a breeding ground for terrorism

In 2006, Nasser al-Wuhayshi was among 23 people who tunnelled out of Sanaa's political security central prison, the most notorious in Yemen. Wuhayshi, who served as Osama bin Laden's secretary in the mountains of Tora Bora, arrived in Afghanistan as an ordinary Yemeni youth in the 1990s, but later became one of the world's most wanted men until his death more than two decades later in 2015.

Instead of repenting, ideologically recanting, collaborating or breaking under torture, he started a jihadist school inside the Sanaa prison - one of the seeds of what became, soon after Wuhayshi's great escape, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Hundreds of millions of dollars were spent in a hunt for Wuhayshi by Yemen, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the United States.

Unprecedented attacks

In 2009, as Wuhayshi was declared the chief of AQAP, Egypt's state security arrested an infamous smuggler in the Sinai Peninsula: Shadi al-Menei, a young descendant of the Sawarka tribe. Without trial or any legal procedures, Menei was transferred on an administrative detention warrant to the Burj al-Arab maximum security prison, one of Egypt's most notorious, west of Alexandria.

In the second half of 2010, the man who once tortured African migrants in the Sinai desert to extort money from their families walked out of prison sporting a beard and a prayer callus.

He soon became known as Abu Mosaab, and after the Egyptian revolution in January 2011, he became the prominent face of Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, the terrorist umbrella group that attracted jihadists from as far away as Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Libya and Sudan. He committed some of the most unprecedented attacks in the history of Egypt, and later pledged allegiance to the Islamic State (IS).

Today, prisoners reel from life-threatening conditions in prisons crammed with tens of thousands of inmates, most sentenced without due process or legal defence

Once again, the criminal Menei didn't transform into a law-abiding citizen and launch a community service project, but rather graduated from the radical jihadist schools operating inside Egypt's prisons, right under the eyes of the country's security apparatus.

These stories are not fiction; these events happened and will continue to happen, especially in Egypt over the next four years, under the presidency of military strongman Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. That is, of course, if Sisi abides by the constitution and steps down after his second term.

Torn by polarisation

"We fight terrorism on behalf of Egypt and the world," Sisi says repeatedly in his public appearances. But the truth is that the iron-fisted Sisi regime is fuelling one of the most dangerous radicalisation phenomena in the history of Egypt. What is taking place inside Egypt's prisons, and outside for that matter, is far more severe than the environment that once shaped Wuhayshi and Abu Mosaab.

In an Egypt already torn by polarisation and the turbulent aftermath of the January 2011 uprising and July 2013 coup, Sisi kicked off his rule of almost 100 million people by killing close to 1,000 on the streets of the capital Cairo, in broad daylight, in August 2013 - an incident rightfully described by international organisations as the worst act of mass killing in the modern history of Egypt. This alone converted hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood youth from reformist activists into ticking time-bombs seeking vengeance.

In December 2017 and January 2018, in reaction to terrorist attacks that the regime failed to counter, more than 20 inmates were executed, in a particularly disturbing act by Egypt's military regime.

Inside the walls of those prisons, and outside for that matter, jihadists and takfiri preachers have been enjoying an unprecedented opportunity to spread their call. The regime's brutal acts against the population provide terrorist organisations and extremist ideologues with the required narrative to attract infuriated civilians.

Sinai Province remains the prime example, with periodic messages focusing on the military policies of collective punishment in North Sinai, including the destruction of entire villages and acres of farms, and the extrajudicial execution of civilians.

Lethal crackdown on Islamists

Terrorism isn't new to Egypt. Ayman al-Zawahiri, his brother Muhammad, and a long list of the world's most infamous terrorists are Egyptian, were imprisoned in Egypt, and were influenced by or left their influence on jihadist schools inside the country's prisons - but the difference between Hosni Mubarak's Egypt and Sisi's, despite the waves of terrorism that hit both, is very stark.

Under Mubarak, despite the lethal crackdown on Islamist groups in the aftermath of the 1997 Luxor massacre, the regime understood that bullets alone wouldn't lead to a permanent solution or influence the views of those killing in the name of their extremist religious beliefs.

Ironically, it was Habib el-Adly, the former head of the death-under-torture State Security Investigations Service, who launched a dialogue with the top figures of Islamic Jihad and al-Jamaa al-Islamiyya, whose leader co-planned the assassination of President Anwar Sadat in 1981.

Some Islamists saw this dialogue as treason, while others believed it was an attempt to neutralise former militants to infiltrate the country's Salafist community - but the fact remains that this dialogue led to some of the most influential ideological recantations in the history of radical Islamist movements across the world.

Examples include Nageh Ibrahim, Islamic Jihad's top officer who personally massacred police personnel in 1981, and Sayyed Imam al-Sherif, al-Qaeda's revered preacher and one of the most influential figures in the global jihad movement, both of whom contributed significantly to the successful efforts to sway thousands of Egyptian Islamists away from militancy and violence.

Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh - the defected member of the Muslim Brotherhood who was black-balled by the group for being a reformist, and the founder of the Strong Egypt Party - was imprisoned on terrorism charges simply because of a television interview in which he discussed how Sisi's regime was wrecking the foundations of a stable Egypt and the cohesiveness of its institutions, including the military.

Aboul Fotouh's family recently announced that he received no medical attention after suffering a stroke in prison: "The regime is killing my father," his son, Ahmed, said in a Facebook post.

A state of desperation and hopelessness

It is people like Aboul Fotouh who can - without firing a single bullet, and certainly without torture and extrajudicial killings - stand in the face of the rising tide of radical and militant ideology that capitalises on the unprecedented injustice and humiliation that millions of Egyptian are subjected to, regardless of their backgrounds and beliefs. But these are also the ones who are most targeted by Sisi's regime.

"What the Egyptians would like to do is kill their way out of the problem," Kenneth Pollack, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a Washington think tank, said in a recent interview about Sisi's military policies in Sinai. But the reality is far worse: Sisi's regime has been killing its way through every security, political, economic or social issue facing Egypt since 2013.

Desperate youth [are] lined up at the gates of militancy - and with a final push or a coincidental release from prison, there will be a fanatic preacher, an explosive vest and an AK47 waiting for them

Sisi and his regime aren't fighting terror, neither on behalf of Egyptians nor on behalf of the world. They are creating and sustaining a state of desperation and hopelessness, crushing the already dwindling belief that change can be accomplished through peaceful means, and leaving a vacuum for terrorist groups to fill.

Yemen's Wuhayshi and Sinai's Abu Mosaab could be seen as exceptional cases, but what is unarguable is that Egypt's prisons, far-flung villages and even major cities are harbouring thousands of desperate youth lined up at the gates of militancy - and with a final push or a coincidental release from prison, there will be a fanatic preacher, an explosive vest and an AK47 waiting for them.

- Mohannad Sabry is an Egyptian journalist, expert on security and the Sinai Peninsula, and author of Sinai: Egypt's Linchpin, Gaza's Lifeline, Israel's Nightmare. Sabry has been living in exile since the release of his book in November 2015 and its quick ban in Egypt soon after publication. Sabry was named a finalist for the 2011 Livingston Award for International Reporting, and was among PBS Frontline's team nominated for the Emmy Award for News and Documentary for their 2013 show "Egypt in Crisis".

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

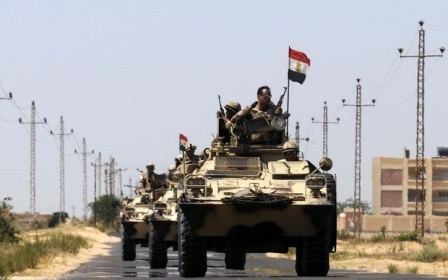

Photo: Egyptian soldiers march on the banks of the Suez Canal during a ceremony on 6 August 2015 (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].