Libya conflict: Is France an honest broker?

On 29 May, France is expected to convene an international meeting on Libya. The meeting is expected to bring together the main Libyan political leaders, including Ageela Saleh, the head of the House of Representatives in Tobruk, Khaled Meshri, the head of the High Council of State in Tripoli, Fayez Serraj, the head of the Presidential Council, and Khalifa Haftar as head of the Libyan National Army (LNA) in the east of Libya.

France has reportedly also invited many countries involved in Libya's conflict, including the other four permanent members of the UN Security Council, as well as Italy, Germany, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar and all of Libya's six neighbours.

The European Union, the African Union and the Arab League are also invited. The main objective of the meeting is to get all four Libyan sides to commit to an agreement under the auspices of the UN and to quickly start arrangements for staging elections before the end of 2018.

A breakthrough agreement?

However, according to a widely circulated draft document, France is pushing for the signing of an accord that consists of (13) key points which include: immediate unification of Libya's central bank, consultation on developing a timetable for holding a referendum on the draft constitution, before or after the elections, adoption and implementation of electoral laws for the proposed 2018 elections and the holding of a politically inclusive conference in Libya or abroad to follow up on the implementation of this accord, within a period of three months.

Should this meeting go ahead in Paris as expected or soon after, it will not be the first one that France has organised. In July 2017, the newly elected French President Emmanuel Macron hosted a similar meeting in Paris between head of the Government of National Accord Serraj and Haftar.

France could be heading for scoring another short-lived diplomatic success by holding a high-profile conference on Libya, which will not actually change much of the realities on the ground once again

That one-day meeting produced a 10-point statement signed by the two men, which was described as a breakthrough agreement, in which they committed to a ceasefire and to hold national elections "as soon as possible".

In hindsight, the meeting, which was also attended by the then newly appointed UN special envoy to Libya, Ghassan Salame, produced no tangible results on the ground and was seen more as a diplomatic success for the new French president rather than a breakthrough in the Libyan conflict.

Italy was angry and critical of the French move and saw France as trying to take full ownership and recognition for resolving the Libyan conflict.

Suspicions are still high though, especially from the Italian side, over the real motives behind France's desired new leading role in Libya and its gathering of this international conference, especially at a time when Italy is occupied with its own internal dynamics and going through a government change.

The real motives

Italy is likely to have a new right-wing government formed by a coalition of the Five Star Movement (M5S) and the nationalist far-right League party, which are poised to take power led by Giuseppe Conte as prime minister.

Italian politicians see the sudden growing French political engagement with Libya, at the highest level, as effectively sidelining Italy and compromising its interests in Libya, which concentrate primarily on the stemming of the flow of migrants across the Mediterranean and the supply of Libyan gas as well as other commercial gains for Italian companies.

Italian politicians see the sudden growing French political engagement with Libya, at the highest level, as effectively sidelining Italy and compromising its interests in Libya

France sees tackling Islamists and the threat of terrorism as the main priorities in Libya, rather than migration, which does not affect France as directly as it does Italy. France is also actively pursuing commercial gains in Libya - only last month the French energy company Total substantially raised its presence in the Libya energy market with the purchase of a 16.33 percent stake in Libya’s Waha concessions from US Marathon Oil for US$450m.

The deal is expected to give Total access to major oil reserves with immediate production and a significant exploration potential as well.

The speed and vigour with which France is getting involved in Libya has also led to many questioning whether it can be seen as an honest broker, given its well-known military and logistical support for Haftar and its close alignment with both major Arab sponsors of Haftar, the UAE and Egypt.

France's shift

Frances’s shift towards supporting Haftar has been mainly championed by the foreign minister in the new Macron government, Jean-Yves Le Drian, who also served as minister of defence from 2012 to 2017 in the government of previous president Francois Hollande.

Over the past three years, France has supported Haftar militarily by deploying advisers and special forces to the east of Libya. France publicly acknowledged its military support in July 2016 after three French special forces soldiers were killed in a helicopter crash near Benghazi.

France's embrace of Haftar has given him political and military legitimacy, made him more acceptable on the international stage and emboldened him in his military campaign that began in 2014.

Historically speaking, Libya was not a French colony such as neighbouring Tunisia and Algeria but France did have a brief direct administrative rule (1944-1951) over the southern Libyan region of Fezzan, following Italy's defeat in the Second World War.

A coordinated step

One of the key aims of the proposed Paris meeting is to push for quick presidential elections in Libya before the end of this year and even before a new constitution is adopted through a referendum. Many see this as a coordinated step between France, the UAE and Egypt towards promoting Haftar's takeover in Libya, mainly through a rushed election while he is enjoying a wave of rising popularity.

The three countries are also actively supporting and encouraging Haftar to take military control of the city of Derna in the east of Libya, in order to boost his military position and give him entire control over the east. The military campaign against Derna has already started early this month, with expected grave consequences for the city and its civilians.

It is clear that France sees Haftar as the potential ally which could best serve French interests both in Libya, and the wider north and west Africa region, including bolstering France's nearby allies in Chad, Niger and Mali.

France seems very much in a hurry to push its narrow agenda in Libya and drag all the different Libyan and international stakeholders along to support it. However, countries such as the US and Italy have recently voiced concern over holding elections without any strong constitutional foundations.

Many crucial and influential Libyan sides also insist that any elections should only come after a new permanent constitution is adopted through a referendum.

France could be heading for scoring another short-lived diplomatic success by holding a high-profile conference on Libya, which will not actually change many of the realities on the ground once again. The fundamental problem is that France is not perceived by many as an honest broker in Libya, but rather biased in favour of one side over another in the deeply polarised conflict.

As one expert on Libya put it: France's one-sided support of Haftar will only add to the thick muddle of foreign interference in the Libyan conflict. A sustainable genuine resolution to Libya's conflict can only be achieved by promoting civilian rule based on rule of law, good governance and building of democratic institutions.

Regressing from the rule of a despotic military dictator to another one is not a viable solution in Libya.

- Guma El-Gamaty is a Libyan academic and politician who heads the Taghyeer Party in Libya and is a member of the UN-backed Libyan political dialogue process.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

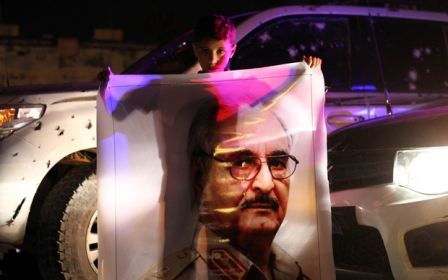

Photo: French President Emmanuel Macron and General Khalifa Haftar, commander of the Libyan National Army (LNA), attend a press conference after talks about easing tensions in Libya, in La Celle-Saint-Cloud, near Paris, on 25 July 2017 (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].