How bulldozers, Bedouin and ethnic cleansing herald the death of the two-state solution

KHAN AL-AHMAR, Occupied West Bank - It takes barely 30 minutes to drive from Jerusalem to the doomed Bedouin community of Khan al-Ahmar, on the main road to Jericho on the West Bank.

But there's no turning off the main road. We have to park in a nearby lay-by, jump over metal barriers, dodge fast oncoming traffic, then scramble up a steep slope to reach the village.

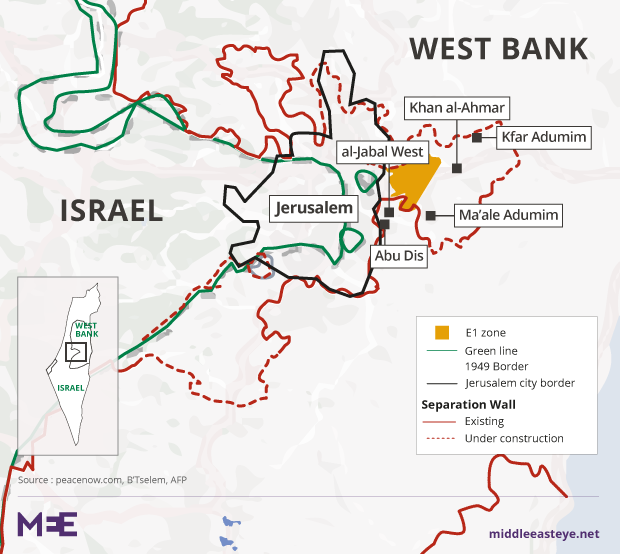

Khan al-Ahmar is home to 173 people, many of them Bedouin shepherds who have lived in the area since time immemorial. But the Israeli state is determined to demolish it to make way for the expansion of the nearby settlement of Kfar Adumim.

Three weeks ago, after years of legal battles, the government received clearance from the Supreme Court to relocate the Bedouin. The judges ruled that the demolition can go ahead because the Bedouin do not have building permits. But this is a sham: the Bedouin have no way of getting permits.

I was born here. They are the ones who came afterwards. We won't leave, whatever happens. We will stay here

- Ibrahim Jahalin, Bedouin shepherd

As far as the Bedouin are concerned, now it's just a case of waiting for the arrival of bulldozers and the Israeli army to drive them out.

They have been designated a new home next to a garbage dump in East Jerusalem. In this urban location, about which they were not consulted, there is no room to graze their flocks and little prospect of other work. Indeed, the Bedouin say that their proposed new home is foul-smelling, contaminated, toxic and unfit for human habitation.

I travel with a guide from the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem. When we reach the village we meet Ibrahim Jahalin, a shepherd. His 11-year daughter plays nearby. What will he do, I ask, when the bulldozers come?

"Why should I even have to go anywhere?" he says. "I was born here. They are the ones who came afterwards. We won't leave, whatever happens. We will stay here."

Series of humiliations

This threat of resettlement is just the latest in a series of humiliations meted out towards the Palestinian Bedouin by the Israelis.

Jahalin belongs to a tribe who were expelled from the Negev desert by the Israeli military during the 1950s. They moved to where the neighbouring settlement of Kfar Adumim is now, but were then expelled from there as well.

Israel denies the Bedouin access to public services and basic infrastructure, as it does to most Palestinians living in Area C of the West Bank. They have no access to the electricity grid. In 2015 the Israeli civil administration confiscated 12 solar panels that had been donated to the Bedouin, although these have since been won back following a legal battle.

There is no access to the Jericho-Jerusalem highway, even though it's barely 100 metres away and we can hear the cars rushing past as we talk.

Ibrahim tells me: "It takes 10 minutes to get to Jericho on the highway. Because we are disconnected from the road, it takes half an hour."This isolation has tragic consequences. Ibrahim lost his young daughter, Aya, in a domestic accident. He blames delays in getting her to hospital. "She died, but she could have been saved," he says.

Ibrahim and I talk in the yard of the nearby school, to the sound of children singing in the classroom. The site, which serves more than 150 pupils, many from neighbouring communities, is also scheduled for demolition.

I tell Ibrahim about the mounting anger in Britain and the West at plans to demolish his village. Boris Johnson, the British foreign secretary, is "deeply concerned," while 100 MPs have written to the Israeli ambassador, suggesting that the demolition may breach international humanitarian law.

But the Bedouin are understandably cynical about this latest manifestation of Western concern. They are all too used to shows of support from the West that mean nothing.

The village's visitors' book reads like a roll call of the great and good. Alistair Burt, UK Minister of State for the Middle East; his predecessor, Tobias Ellwood; Ed Miliband, former leader of Britain's Labour Party; Valerie Amos, the UN Under Secretary for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator; Martin Schulz, former leader of the German Social Democratic Party; Emily Thornberry, the UK Shadow Foreign Secretary; William Hague, the former UK foreign secretary - all are among the 60 odd names in the book.

Briefings have been held in the UN, the British Parliament, the European Parliament, in Sweden, Norway. It has had absolutely no effect on Israel.

If Israel goes ahead with demolition then it will be a defining moment in the history of the occupation of the West Bank. For the past few decades, Israel has pursued a policy which, for the most part, has stopped short of forced population transfer.

Instead the authorities have made conditions so dreadful for Palestinians in the hope that they eventually move of their own accord. Now they are moving towards deportation: in effect the replacement of one ethnic group by another through violence.

That's ethnic cleansing.

In the words of B’Tselem: "This is not a trivial or insignificant violation of international humanitarian law, but a breach that constitutes a war crime."

'Step-change' in occupation

After our visit to Khan al-Ahmar, we go back to the road and drive up to the neighbouring settlement of Kfar Adumim. We pass small businesses, a photographic studio and a primary school. In glaring contrast with our journey to the Bedouin village, access is easy along metalled roads. The settlers live in comfortable detached houses with sweeping views over scenery resonant of the Bible.

We park at the top of the hill and look down at the Bedouin village below.

I asked myself: what do the settlers see when they look down on the Bedouin? Criminals? Terrorists? A human sub-species which can be disposed and redisposed of at will?

Ibrahim told me: "I fear it will happen this weekend when there is a holiday at the end of Ramadan."

It looks inevitable that this community will be swept away and become another casualty of the occupation. And that will be a giant step towards the creation of an urban settlement block that would split the southern and northern parts of the West Bank in two.

It will also mean a step change in the occupation as Israel moves to a policy of forcibly transferring other communities. And the two-state solution will look that much more like a ruined dream.

- Peter Oborne won best commentary/blogging in 2017 and was named freelancer of the year in 2016 at the Online Media Awards for articles he wrote for Middle East Eye. He also was British Press Awards Columnist of the Year 2013. He resigned as chief political columnist of the Daily Telegraph in 2015. His books include The Triumph of the Political Class, The Rise of Political Lying, and Why the West is Wrong about Nuclear Iran.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Ibrahim Jahalin, a Bedouin shepherd, has vowed to stay in Khan al-Ahmar "whatever happens" (MEE/Peter Oborne)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].