#NoBan: One woman's World Cup fight to open stadiums to Iranian women

LONDON – Maryam Qashqaei Shojaei grew up watching football on TV with her mother in Iran. Her mother used to reminisce about attending sports matches in stadiums in Tehran prior to the 1979 Iranian revolution.

At the time, being allowed the same freedom seemed unimaginable to Shojaei, but today, she is without any doubt that it is attainable.

“When I was little, it was quite normal to me that as girls we would not go into the stadiums to watch the matches,” she tells Middle East Eye. “My mother would talk about attending [before 1979] and it seemed… unbelievable.”

When I was little, it was quite normal to me that as girls we would not go into the stadiums to watch the matches

- Maryam Qashqaei Shojaei

Shojaei, an Iranian activist who moved out of the country around 10 years ago, has made international news in recent weeks as she came to Russia for the 2018 World Cup tournament, not just as an avid football fan, but to raise awareness for a “basic” and “fundamental right”, which is allowing women to enter Iranian sports stadiums.

Iran was the only country that participated in the FIFA tournament, Shojaei says, with a ban on women entering sports stadiums. In fact, Saudi Arabia, which has traditionally imposed strict regulations against women in sport, overturned their own ban, allowing women into football stadiums for the first time this year.

While the day before Iran’s second World Cup game against Spain on 20 June, local news agencies reported that women would be allowed to enter Tehran’s Azadi Stadium to watch a live broadcast of the game, the officials did not say whether the decision to lift the ban was permanent.

A series of pictures captured on social media and in news reports showed women sitting in the Azadi stadium for the first time in around 38 years, which Shojaei agrees was a momentous occasion. But she also says that “we don’t know if this is going to be a permanent situation or one for just a temporary amount of time. We just don’t know. But it is progress.”

The Washington Post reported that the authorities had cancelled the event at first, citing technical difficulties, but when fans turned up anyway, they caved in and allowed men, women and children in.

“Even when they arrived there was still some disagreement about whether they would be allowed in… some of them returned home. It was an hour and a half before the game that people really found out that women could go in."

#NoBan4Women

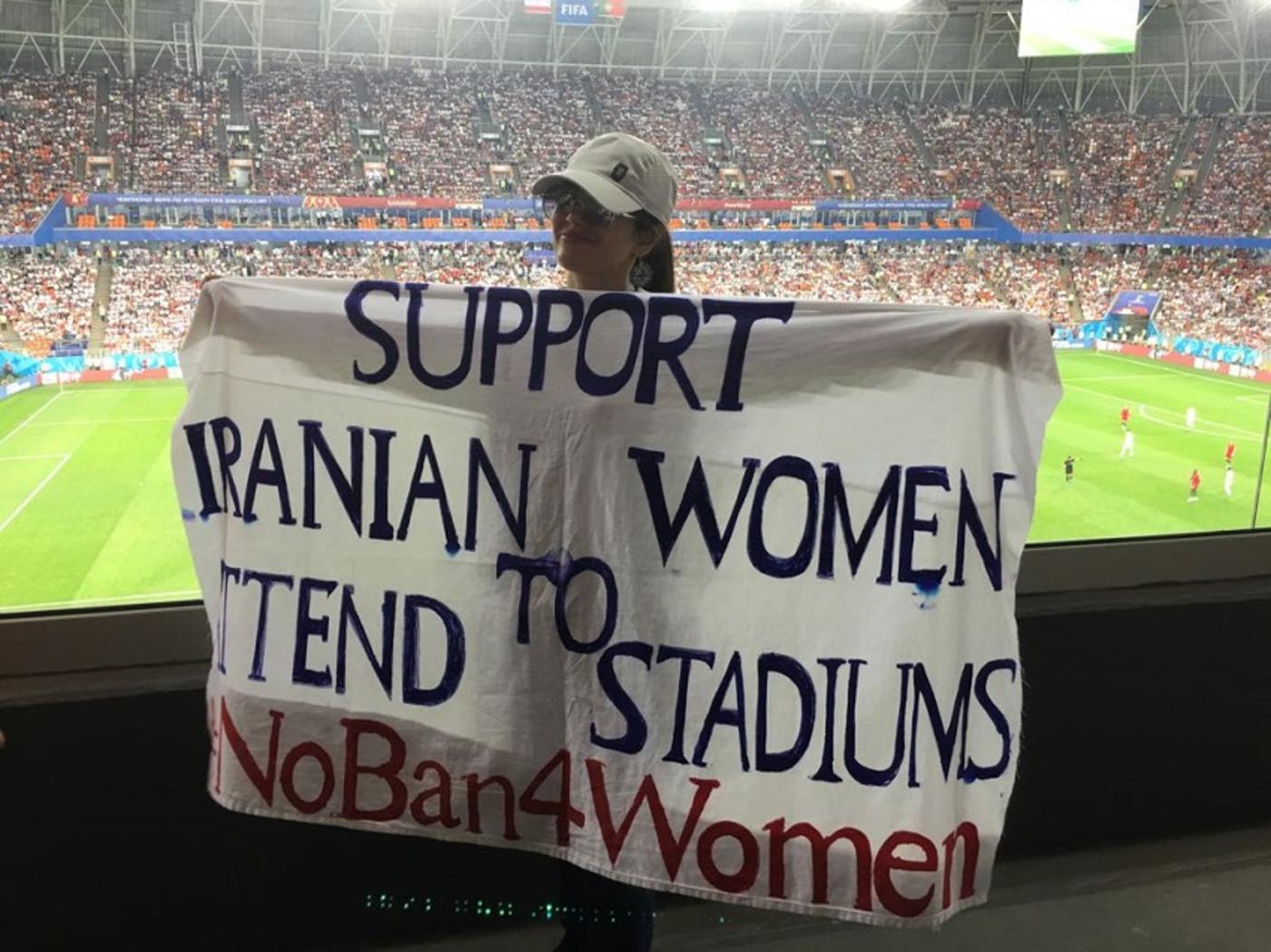

Having secured a surprising green light from FIFA because her demonstration was justified as a social movement rather than a political protest, Shojaei got ready to protest at Iran’s second World Cup match against Spain at Kazan arena. She had already raised banners reading #NoBan4Women during round one when Iran faced Morocco in St Petersburg.

Even though she had gotten advance approval, Shojaei was stopped by Russian security before being able to protest as planned.

“No matter what can be said about the Iranian police, compared to the Russians (security) they are angels,” says Shojaei, adding that despite the bad reputation of Iranian police, they are at least “polite”.

According to Shojaei, it took some time for her to explain to Russian security that she had prior approval from FIFA, but they did not appear to want to listen. She was held for two hours, missed the first half of the match and was told her banners had been placed in a bin - a fact she later found to be untrue. She picked the banners up at the stadium in Saransk before Iran’s third game.

Shojaei’s banners solidly urged FIFA to “Support Iranian Women to Watch Sports in Stadiums,” followed by the hashtag #NoBan4Women. She also carried one banner written in English and Farsi for good measure.

There was no fourth match, as Iran’s hopes at the World Cup were dashed when they lost to Spain 0-1 and tied with Portugal on 26 June, drawing 1-1 and coming third in their group, effectively ending their World Cup run.

Shojaei believes that lifting the ban permanently should be an easy win. After all, the ban, she says, “is not a law. It should not be hard to overturn it. This is not an impossible thing to do.”

The ban on women entering stadiums started after the 1979 Iranian revolution, allegedly to shield women from inappropriate behaviour inside stadiums, including swearing and cursing.

“The ban happened very gradually, there was no announcement. During 1979, there were no games being played anyway - the country was in chaos. After the revolution, some games were played but only men attended and since then women never attended.”

Inspiration in Brazil

Shojaei’s own work to get women inside stadiums started four years ago. She started her advocacy in order to raise awareness inside Iran through her organisation My Fundamental Right alongside other grassroots organisations like Open Stadiums. Through social media, they used visuals such as photos and videos of people voicing their support for the cause. She believes that this has worked as it has sparked a huge conversation in the country.

[I saw] so many different people of all ideologies, of all nationalities, men, women, children, speaking Farsi and coming together to watch Iran play

- Maryam Qashqaei Shojaei

“It was only when I was outside of Iran that I decided to try and change things,” she says. Shojaei lives abroad but prefers not to disclose her location for security concerns.

Shojaei says that when she went to the 2014 World Cup tournament in Brazil and saw “so many different people of all ideologies, of all nationalities, men, women, children, speaking Farsi and coming together to watch Iran play,” she realised it was a tool for unification.

Iran’s first game with Morocco sparked similar feelings as she walked into the Krestovsky Stadium because she felt as though she was walking into an Iranian stadium.

“I had never seen so many Iranian people outside of Iran. So many people speaking Farsi, women were high-fiving each other. Yet at the same time there was a part of me that felt guilty for being in that beautiful stadium when there were so many girls who didn’t get that chance.”

FIFA comes into play

Shojaei says that the reforms FIFA adopted that place women’s rights within their statutes can work to their advantage and be used to place pressure on Iran.

“For not acting, FIFA is violating its own protocols.”

It’s surprising because there are more women working within FIFA now but they are not really active on this cause

- Maryam Qashqaei Shojaei

Shojaei refers to a number of reforms implemented by FIFA in 2016, following a corruption scandal that hit the federation the previous year. These included the promotion of women in football and the enshrinement of human rights within its statutes.

“It’s surprising because there are more women working within FIFA now but they are not really active on this cause. I’ve even tried to reach out to [female officials] while here in Russia, but they’ve claimed to be really busy."

During a visit to Iran in March, FIFA President Gianni Infantino attended a match between two Tehran clubs at the Azadi stadium. While he was there, 35 women attempted to sneak into the stadium, but they were held for several hours by security forces.

Shojaei suggests that these young women had felt emboldened by the fact that FIFA officials were sitting inside, believing that nothing would happen, but instead they were led to Vozara Detention Centre in Tehran.

Rouhani pledge

A day later, Infantino told reporters that Iranian President Hassan Rouhani had “promised that women in Iran will have access to football stadiums soon”.

In 2015, former FIFA president Sepp Blatter wrote an open letter that was published in The FIFA Weekly, titled "An Appeal to Iran," which openly criticised Iran’s inaction on its promises to allow women to enter stadiums and attend football matches. “This cannot continue,” he wrote.

Rouhani has supported ending the ban. Around one month after Blatter’s letter, the Iranian Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sport made an announcement declaring that women would be allowed to watch live sporting events, an assurance which did not come to fruition.

Iran’s first women’s football teams were established in 1970. But women’s fascination with football dates to years before that when women would join men by playing in the streets and local teams until it became clear they warranted their own games.

Women’s football in Iran stopped after the 1979 revolution but a revival was seen in the early 2000s and in 2005 a team entered the West Asian Football Federation Women’s Championship.

Now female players are helping to raise awareness of Iran’s stadium ban by voicing their opposition, says Shojaei.

‘Women are ready’

Shojaei recognises that she at least got to hold her banners up so FIFA could acknowledge that Iran is far behind the rest of the world.

The attention has done wonders for her petition, which has already accumulated over 150,000 signatures. Shojaei will now present them to FIFA officials and urge Infantino to use his power to influence Iran to overturn the stadium ban on women.

“Having seen all those women, standing in the stadium taking selfies proudly showed everyone that women are ready, the ban must end.”

*Maryam Qashqaei Shojaei is a pseudonym the activist uses to protect her identity.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].