From the Jungle to the West End: ‘It’s not about refugees, it’s about humans’

LONDON - The Jungle, a makeshift camp in the northern French port of Calais that housed thousands of people from all over the world until it was demolished in 2016, has become a symbol of the times we live in.

Here, in a corner of Western Europe, people who had fled war and terror gathered, hoping to cross the English Channel to build a new life. Hundreds still live in the area the camp once occupied, their lives in limbo.

This summer, a play called The Jungle has brought the story of the camp to audiences in the West End of London, winning rave reviews in the process.

Miriam Buether's set removes you from the West End and places you inside the camp. The Playhouse Theatre's stalls replaced by the roughly thrown together Afghan cafe, assembled on a dirt floor with flags representing the nationalities living there.

A painted wall of the White Cliffs of Dover, on England's south coast, tells us where the camp residents aim to go. With North African music piped in and TVs showing Egyptian dance shows, the cast offer you cups of chai as you take your seat at the hardboard tables.

Written by Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson, The Jungle tells the story of the camp from the point of view of its many residents, who are Kurds, Afghans, Sudanese and Eritreans. It is bookmarked with the death of three-year-old Alan Kurdi, whose drowning off the coast of Turkey sparked an outpouring of horror and sentiment in Europe, and which brings a new kind of resident to the Jungle: the naive and well-meaning English volunteer.

Sympathy turns to hostility with the Paris attacks of November 2015, which also appear as if shown live on TV. Together, the divided residents fight eviction by the French authorities while seeking to take the "good chance" to England - or die in the attempt.

Near the end of this extraordinary play, its narrator Safi, an English literature graduate from Aleppo who is trapped in the camp, faces a terrible dilemma.

A Kurdish people smuggler who has a soft spot for him wants to get him to the UK, the very place he has dreamed of going after so many months of waiting and losing his mind in Calais. But to do so he will have to take the place of a young man from Sudan’s Darfur region, who is more vulnerable and has suffered more than he has, facing death and torture to make it to northern France.

Terrible choice

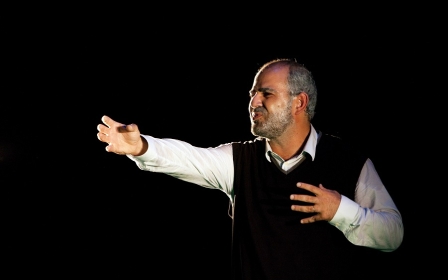

This dilemma is not abstract for Ammar Haj Ahmad, the Syrian actor playing Safi, who, despite his scruffy attire and unkempt hair, sports a kingly beard and has the manner and diction of a cool professor. He ended up seeking asylum in the UK in 2011 and has not returned home to Syria since.

“That was my thought back then," Haj Ahmad tells me when I meet him at a bookshop in central London. "Then I was thinking about: what is the criteria of someone more deserving in the times of catastrophe? Is it the physical house or is it the inner safety? And that is what later started unfolding to me, because lots of people started to travel from different parts of the world for a better life.”

In order to bring the camp's voices to life, writers Joe Robertson and Joe Murphy spent eight months working in Calais with refugees, eventually creating the Good Chance Theatre there so the stories of the Jungle's residents could be told.

Good Chance

The attitude of equality and community created by the theatre is one that is carried throughout the play, says Haj Ahmad.

“Good Chance is one of the rare organisations that treated refugees as potential rather than victims… It's all about giving on equal terms: show me what you’ve got and I’ll give you everything. And to me this is what defines home."

The play evolved over two productions and a total of 18 months of workshops, during which Haj Ahmad more than once nearly walked away. Co-director Stephen Daldry, a British theatrical heavyweight best known for creating the hit musical Billy Elliott and more recently producing the Netflix drama The Crown, was changing the script right up to the first night, says Haj Ahmad, who adds that “eighty percent of what you see in the play happened in the Jungle".

Magic circle

The Syrian remembers Daldry telling the cast, half an hour before press night: "I don’t have anything to say to you. But I tell you one thing: the task of this function is to change the world, go and change the world."

After that, Haj Ahmad says, "we went silently to our dressing rooms and we came back to do the press night, and it was incredible.”

Neither the writers, directors nor the cast could have known how powerful the reaction to the piece would be when it was first performed in November at London's Young Vic theatre. “Before we jumped on stage at the Young Vic after the last rehearsal, I don’t know where we were really. And then we went to the stage, and we saw the Afghan restaurant, in the tech rehearsal. We cried like children. Suddenly it’s home.”

Audiences and critics were blown away. Word spread quickly and the show sold out. The actor says this is because the piece is an expression of reality that affects both the cast and the audience. “Each of us is saying every line and opening a window to a relative, to a story we are experiencing right now. The audiences are receiving and identifying and putting it inside them with similar stories they are witnessing on TV. This is like a magic circle.”

For Haj Ahmad, the transition from working in Syria to leading a cast in a hit show in London has not been an easy one. He studied at the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts in Damascus, graduating in 2008. He worked in his homeland for two years, doing 13 TV series and one international film.

In early 2011, the actor was approached by UK-based theatre company Dash Arts, which wanted him to be in its production of One Thousand and One Nights, based on the Arabian classic, in which the actor had to play eight parts. Rehearsals took place in a palace in the old city of Morocco’s Fez.

It was a tumultuous time. As Haj Ahmad puts it: "Egypt was having the revolution, Libya the same, in Syria we didn’t know what might happen - the option was to go to Morocco.”

Leaving Syria

The actor left Syria three days before protests broke out in Daraa on 15 March 2011, and he would never return. One Thousand and One Nights opened in Toronto in the summer and by that time, with violence in Syria escalating, Haj Ahmad didn't think going home was possible. After the tour ended in Edinburgh during the Scottish city's August festival, Haj Ahmad’s visa ran out and he called the British Home Office to apply for asylum.

“It was the hardest decision ever," he says. "To be honest, I felt I was taking someone else’s place, because I flew from Syria as an actor. I was having the best of times. I am on an international stage doing all this, and then you end up with no money, no papers, and you can’t go back home.”

Haj Ahmad did not want to become a dependent or a victim as a result of his asylum status. “At that moment, I said that I’m an actor. I think that I can make my life and I didn’t claim for benefits, I didn’t claim for housing.”

However, this decision generated suspicion, because officially, as an asylum seeker, he was not allowed to work. He stayed with a friend and took work in bars and cafes, a new experience for him.

“In Syria, as an actor, you don’t need to do anything like this. We get paid really, really well… I came here and I thought it’s going to work, but it went into a very hard place.” He was granted asylum quickly but struggled to adjust to life in London.

Haj Ahmad sought out work that was meaningful to him, such as the Palestinian drama Returning to Haifa, by Lebanese writer Ismail Khalidi, which he starred in earlier this year on stage in London. Other offers were less appealing - playing Middle Eastern terrorists of one kind or another - and he sometimes turned them down.

The contrast with the roles he was previously given in Syria amuses Haj Ahmad. “I find it interesting that when I was in Syria in the historical TV series, in most of them I was asked to play the Roman, the Greek, because of my looks, and then I came here and I was offered to play the terrorist. It’s funny.”

Toxic

At the same time, he was staying in touch with people back in Syria via Facebook, where the situation had grown increasingly polarised. “In Facebook it became toxic with what was happening in Syria. People would be sitting in different parts of the world pushing people inside Syria to protest. There are things that I didn’t get. The regime is corrupt. There are no two people who argue about that… I understand the intentions, but I didn’t want to get involved in this."

In the end, he decided to quit Facebook and stayed off it for five years. But he knows all too well the toll the war has taken on Syrians.

“It’s really important to say that lots of people, they did that; they sacrificed their houses, their families, for a principle, and those people exist, and they are there and they lost everything.”

His family too has been “scattered like any other Syrian family. We did lose everything,” he adds. “Everyone who left is traumatised, whether they suffered in Syria or they didn’t; whether they said ‘Angela Merkel’s invited everyone, let’s go’ and stepped on others’ shoulders, or they really suffered. They are all traumatised.”

Trauma

This deep trauma is powerfully revealed in The Jungle when a British volunteer and a teenager from Darfur talk about the terrible ordeals he has gone through to get to Calais: surviving atrocities in Darfur, a deadly crossing of the Sahara, being tortured in Libya, and almost drowning in the Mediterranean.

Haj Ahmad feels passionately that The Jungle is rewriting the rulebook on how theatre is done in London’s West End. Forty percent of tickets have been kept below £25 ($32) - cheap by West End standards - and some have been reserved for refugees and their families.

“It tells you that you can bring people from so many cultures, so many languages, and you create an incredible experience. Yes, some people say it’s written by two white boys who went to Oxford, but look how many people from different backgrounds are in this play.”

He has something else to say: “People want to hug each other after this play. People put signs up in their windows saying ‘refugees welcome’. This show broke the frame: it’s not about refugees, it’s about humans.”

The Jungle runs at the Playhouse until 3 November 2018

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].