Trump's ‘Arab NATO’ idea is doomed to fail

The United States is reportedly floating plans for a new security alliance with six Gulf Arab states, alongside Jordan and Egypt, to counter Iran's growing presence in the region. Provisionally named the Middle East Strategic Alliance (MESA), some have dubbed it an “Arab NATO” of Sunni Muslim allies.

“MESA will serve as a bulwark against Iranian aggression, terrorism, extremism, and will bring stability to the Middle East,” a spokesperson for the White House’s National Security Council told the Reuters news agency.

According to White House sources, the US-proposed alliance would deepen cooperation between the eight Arab countries on a range of security issues, including counterterrorism, missile defence and military training, as well as strengthening economic and diplomatic ties.

We've heard this one before

Like NATO's article 5, which considers an attack against one member state to be an attack against all, collective defence would likely be enshrined into the constitution of an Arab NATO, which would deem an attack by Iran against a member state as an attack against all.

US president Donald Trump will no doubt claim and even believe that not only is this would-be security alliance a product of his genius, but also that it’s never been tried before. Worse, he might even believe it’s not doomed to fail.

If Iranian-led sectarianism is viewed by the Sunni Gulf Arab states as the primary security threat, then these states would be better served by alleviating the concerns of their Shia minorities

Plans for an Arab NATO involving the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states - Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Bahrain - and others in the region are kicked around from time to time, often triggered by the percaption of a shared threat.

When these countries thought of Islamic State (IS) as the primary threat to regional regime survival in 2014, the six GCC states, along with Morocco and Jordan, talked about consolidating their military capabilities into a fully integrated collective defence alliance.

These plans never materialised for a number of reasons, including differing views of the conflict in Syria, Oman’s cordial ties with Iran and Qatar’s support of the Muslim Brotherhood, which is seen as anathema to Egypt’s military junta and the Saudi monarchy.

During the latter years of the Cold War, Arab monarchies viewed Soviet-exported Communism and the Iranian Revolution as the primacy security threats to their regimes. Their collective fears were piqued when the Soviet Union invaded Iran’s neighbour, Afghanistan, in December 1979, and then spiked when the war between Iraq and Iran broke out the following year.

These events led to the establishment of the Peninsula Shield Force (PSF), which was designed to deter Iran from widening the war front to neighbouring Arab states.

Pro-democracy revolution

The PSF collapsed half a decade later, when member state Iraq invaded member state Kuwait. The failure of the PSF to mobilise against the Iraqi invasion not only led to its demise, but also led members to shun collective security alliances in favour of individual security strategies, with the US becoming the protector of choice. This explains why the total number of US military bases and personnel in the region has ballooned in recent decades.

Ultimately, the concept of security is based entirely upon threat perception, with security being defined as the absence of threat to the nation state. Security threats emerging from nearby are considered the most dangerous, but threat perceptions change rapidly - often without warning.

When Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak resigned from office on 11 February 2011, Arab regimes were facing an existential crisis fuelled by liberal democratic solutions for resolving socioeconomic and political injustices. Almost overnight, the threat posed by al-Qaeda to the security of these regimes had been replaced by the threat of democracy.

Three years later, that threat would be replaced with the threat posed by IS. With the threat of the terror group essentially mitigated, Arab states have returned to a fixation on Iran.

Qatar blockade

For a more contemporary example of how quickly collective security alliances can be undone in the Middle East, one can examine the way in which Saudi Arabia has led an Arab blockade against its fellow GCC member Qatar, in retaliation for what the Saudis view as Qatar's all-too-cosy relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Intercept recently learned of a Saudi-led plot to invade and conquer Qatar in 2017. "The plan, which was largely devised by the Saudi and UAE crown princes and was likely some weeks away from being implemented, involved Saudi ground troops crossing the land border into Qatar, and, with military support from the UAE, advancing roughly 70 miles towards Doha," according to the Intercept.

This, again, demonstrates how threat perceptions and security concerns of Gulf Arab states are far from being homogenous, and can change quickly.

If Iranian-led sectarianism is viewed by the Sunni Gulf Arab states as the primary security threat, then these states would be better served by alleviating the concerns of their Shia minorities and granting equal rights and responsibilities to all their citizens.

To this end, the Trump administration is attempting to devise a military solution to a political problem - something that has been tried and failed many times already.

It is for these reasons that an Arab NATO is doomed to fail.

- CJ Werleman is an opinion writer for Salon, Alternet, and the author of Crucifying America and God Hates You. Hate Him Back. Follow him on Twitter: @cjwerleman

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

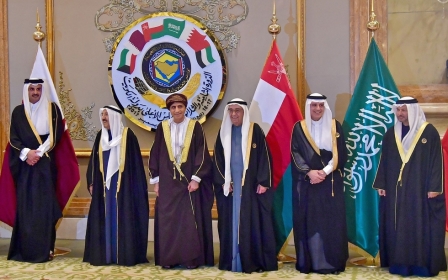

Photo: Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir and Qatari Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani attend the Gulf Cooperation Council summit in Kuwait City on 5 December 2017 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].