Safar: A journey of discovery into Arab cinema's past and present

LONDON - A striking young woman wrapped in a bed sheet sits with a cigarette in hand. Lying beside her is a man she just spent the night with, after sneaking away from a much older husband while he was sound asleep.

“My name is Karima,” she says, which means generous in Arabic. The man slyly responds with "Karima awi ya Karima" – “You are very generous, Karima,” drawing a round of laughs from the audience.

The room at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London was filled to the brim with film enthusiasts who gathered to attend the opening of the 2018 Safar Film Festival, the UK’s only film festival focusing exclusively on Arab cinema.

Watching this reminded me just how hilarious, ridiculous and brilliant [Egyptian films] can be

- Ahmed Abed

Safar: A Literary Journey Through Arab Cinema kicked off on Thursday with a film adaptation of a 1960s novel by the great Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz, the only Arab to have ever won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

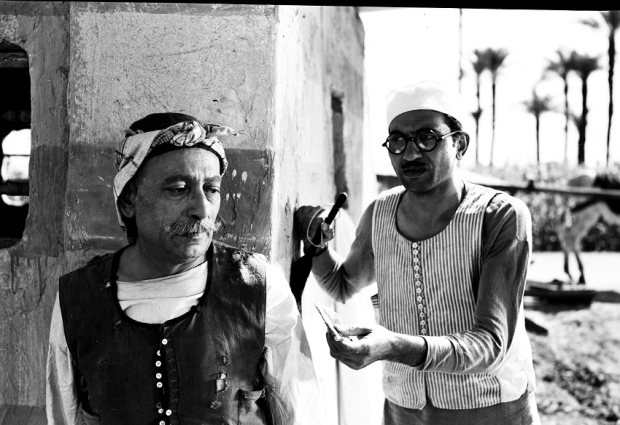

El-Tareeq (1964), the novel-turned-noir-film directed by the late Hossam El Din Moustafa, did not disappoint. The audience wavered between bouts of laughter and gasps of surprise throughout the screening.

“I grew up watching Egyptian films,” Ahmed Abed, a Lebanese member of the audience told MEE, after the screening and Q&A. “Watching this reminded me just how hilarious, ridiculous and brilliant they can be.”

In Cairo, the protagonist falls in love with two very different women, and each one enriches an opposite side of his personality. Karima is played by Shadia, an Egyptian actor and singer who has captivated millions for decades. She appeals to his sordid history as a carefree womaniser and loser with no credentials to speak of.

Souad Hosni, an icon of Egyptian cinema's golden age, plays Saber's other love interest, Nadia, who appeals to the better man he had hoped to become or wished he was. El-Tareeq is the only film to include both iconic women actors, though they do not share any scenes together throughout the movie.

During a camel ride between Saber and Nadia, we see magnificent footage of Egypt's pyramids and the Sphinx. Beyond those historic sites, however, is a massive graveyard, which Saber catches a glimpse of and is greatly disturbed by – a not so subtle premonition of his imminent downfall. Additionally, there are scenes from the now iconic Tahrir square, which was the centre of the 18-day protests that led to the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak in 2011.

But the film also shows a Cairo unknown to many in the West, and it is filled with scenes depicting prostitution, class divisions, and agnosticism over the political milieu.

Saber's failed search for his father seems to hint at the disconnect some Egyptians felt in the midst of the era of nationalist president Gamal Abdel Nasser, the colonel who led a coup with a group of officers against the monarchy in 1952, implying that an Arab or Egyptian “saviour” never emerged, though one was gravely needed. Three years after the film's release, Egypt faced a colossal defeat in the 1967 Six Day War when it lost the Sinai Peninsula to Israel.

In one scene that captures this theme of hopelessness beautifully, Saber spots his father in a luxury car, and rushes towards it as it speeds away.

My films take me back to my roots. The camera is my best friend

- Koutaiba al-Janabi, Iraqi film director

For curator Joseph Fahim, an Egyptian film critic and programmer, the choice for the opening film wasn’t an obvious one. Al-Tareeq is a lesser-known Mahfouz novel and by extension a lesser-known film adaptation, when compared to, for example, Adrift on the Nile or The Beginning and the End.

Fahim said he has a soft-spot for the film because it was the first he ever wrote a review about while he was still a student at university in Cairo. That review set into motion his career in film critique and curation. Fahim said he grew up rebelling against parts of his Egyptian identity, and instead chose to immerse himself in American film, but would later come to embrace his homeland’s rich cinematic heritage.

“I started questioning myself and asking: why is everyone turning to [Alfred] Hitchcock, or to French new wave cinema, for example? No one knows anything about Arab cinema. But there’s such great talent out there.”

The golden age

Egypt entered what is referred to by many as “a golden age of cinema” in the 1950s, as Nasser sought to reclaim the country’s narrative from colonial influences following the 1952 coup. Consequently, the works of some of the country’s biggest novelists of that era, including Yusuf Idris, Tawfiq al-Hakim and Mahfouz, were adapted into film.

The works hail from Tunisia, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria and beyond. Some of the movies have been subtitled in English for the very first time, and many are UK or European premieres. The festival is also offering a series of satellite programme events, as well as book club discussions.

“We’ve really gone deeper into the conversation, rather than just screening the films. We’re taking the conversation beyond the festival,” Nadia El-Sebai, the executive director of the Arab British Centre, told MEE at the festival opening. “We want people to come away with a feel for the diversity in Arab cinema, as well as Arabic literature.”Innovative storytelling

Not all of the festival’s entrants are based on works of literature, with some derived from innovative styles of storytelling, including autobiographies and oral folk narratives.

One of these films is Koutaiba al-Janabi’s Stories of Passers Through (2017), which features archival footage documenting the filmmaker’s life in exile over the last three decades. Janabi, a London-based Iraqi film director, was forced to leave his home country at the age of 17 due to “the brutality of the Saddam Hussein regime”.Believe me, nobody wants to be a refugee. I am here, but I am not here

- Koutaiba al-Janabi, Iraqi film director

Janabi’s film, which screens at the ICA on Friday in its Europe premiere, reflects his personal story of “alienation, longing, fear, [and] escape with an experimental approach to style and narrative”.

The film fuses different forms of archival footage shot by Janabi since after fleeing his country in the 1970s, passing through Hungary where he received a degree in cinematography at the Academy of Drama and Film in Budapest, to where he ended up, in London.

It also has roots in tragedy: Janabi’s father, who was a politician, was executed by Saddam's Baath party when the filmmaker was just a boy.

"The loss encouraged me to find my roots," he said. “I had to put the small pieces of my mosaic together and create something. Many write their diaries with paper and pencils. I wrote mine with pictures."

Stories of Passers Through is the second independent film in a trilogy that draws from Janabi’s life experiences. The first part of the trilogy, Leaving Baghdad (2012), won several awards including the Raindance Award at the largest festival of independent film in Britain.

“I try to create a feeling of what it is like to be away from one’s homeland, to show the human element of living in exile. I document these experiences to reflect some of what an entire generation of people living in exile feel.”

Janabi, who visits Baghdad once a year, said that the Syrian and Iraqi refugee crises “made him boil from the inside,” prompting the director to finish his films sooner than originally planned. His third film, The Woodman, will likely be complete by the end of the year.

“Believe me, nobody wants to be a refugee. I am here, but I am not here,” he said, referring to his thoughts being scattered between London and Baghdad.

“My films take me back to my roots. The camera is my best friend," he added.

Lack of archives

For Fahim, putting together the festival was an exercise in patience and one that underscored the extent to which the Arab world’s cinematic productions have varied considerably from country to country over the years.

Fahim laments the lack of film archiving across the region - barring efforts from private institutions.

The Arab world does not care [about archiving its films]

- Jospeh Fahim, curator of Safar Film Festival

“The state of archiving and of restorations and preservations is exceedingly destitute,” he said, adding that rights owners were difficult to locate and that he had to “deal with a lot of bureaucracy to secure the films.” In some Middle East nations, particularly war-ravaged Syria and Iraq, the fate of a swathe of Arab cinematic heritage is “simply unknown”.

“The Arab world does not care [about archiving its films],” he said. Though Tunisia and Lebanon have made some progress in that respect, the region does not yet have the equivalent of the British Film Institute, for example.

A diverse selection

Other movies on the Safar programme include Poisonous Roses (2018), directed by Egyptian filmmaker Ahmed Fawzi Saleh. The film is based on the nineties cult novel by Ahmed Zaghloul al-Sheety. The movie, which is set in the impoverished, rough alleyways of Cairo’s tannery district, centres on a sister obsessed with her brother’s desire to flee their destitute life.

In the Land of Tararanni - a 1973 Tunisian film adapted from an anthology penned by Ali Douagi, the first Tunisian writer to popularise short stories - tells three stories set in the country in the 1930s.This is not the definite last word on literary adaptations. I hope this is the start of a long conversation

- Jospeh Fahim, curator of Safar Film Festival

Scheherazade’s Diary (2013) tracks the women inmates of Baabda prison in Lebanon as they participate in a theatre initiative set up in 2012 by drama therapist Zeina Daccache, who directed the documentary. The women candidly open up about their harrowing pasts, which include domestic violence and childhood trauma, using ancient Arab traditions of storytelling.

Also of note is Wajib, Palestinian director Annemarie Jacir’s third feature film. The movie follows a man’s journey across Nazareth with his estranged son to deliver wedding invitations for his daughter to her guests by hand.

The festival will close on 18 September with the world premiere of the 1969 film, The Land, directed by Youssef Chahine, one of the leading voices in Arab cinema for over half a century until his death in 2008.The film is celebrated as one of Chahine's most popular works in his homeland, Egypt, and is based on a novel by Abderrahman Sharkawi. Thought by many to be a reaction to steep regional losses following the Six-Day War, the film is set in 1930s Egypt and focuses on a group of farmers seeking to wrest control of their land from feudal lords. A Q&A with Ahdaf Soueif, one of Egypt's leading novelists, will follow the screening.

“Every movie represents a different proposition,” Fahim said. “There is so much more to explore. This is not the definite last word on literary adaptations. I hope this is the start of a long conversation.”

Safar: A Literary Journey Through Arab Cinema opened on 13 September in London and will run through 18 September, with screenings taking place at the ICA and Institut Francais.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].