What does the latest vote mean for Iraq's Kurdish region?

Following a dramatic independence referendum and increasing disunity among Kurdish parties, last month’s parliamentary elections came at a crucial juncture for Iraq’s Kurdish region.

The vote on 30 September came a year after the historic independence referendum, where national pride was quickly replaced by animosity after Baghdad’s heavy-handed response led to the loss of Kirkuk and other disputed territories, as well as punitive measures against the region.

The fallout led to the reemergence of old enmities between the two ruling parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). The discord was evident as the two parties were at loggerheads over their nominations for the Iraqi presidency.

Power-sharing deal

In the end, Barham Salih, the PUK nominee, won by a comfortable margin as the decision went to a vote by the Iraqi parliament. The KDP did not hide its frustration with the PUK and their failure to agree on a single Kurdish candidate, resulting in “other people” and “not representatives of the Kurdistani nation” deciding their fate.

KDP President Massoud Barzani stressed that the Iraqi presidency “is directly associated with the political merits of the people of Kurdistan and it is not exclusive to any person or any specific political entity”.

Divisions between Kurdish parties have been worsened by infighting and leadership battles; the PUK has been gripped by a power struggle since Talabani passed away last year

The KDP and PUK have a long-established power-sharing agreement that has not resulted in a unified administration, such as a single command of the Peshmerga forces, but has instilled a degree of balance between both parties. The emergence of the Gorran (Change) movement in 2009, however, shook up the status quo. As Gorran splintered from the PUK, the latter took big electoral hits in 2009 and 2013.

Now, with the suspension of the Kurdish presidency, the marked decline of PUK seats since 2009, and the death of PUK founder Jalal Talabani, the KDP does not feel that old agreements are reflective of today’s realities. Divisions between Kurdish parties have been worsened by infighting and leadership battles; the PUK has been gripped by a power struggle since Talabani passed away last year.

Salih only recently rejoined the PUK after forming the Coalition for Democracy and Justice as an opposition force. Gorran has also suffered after the death of its own founder, Nawshiran Mustafa, last year.

Alleged fraud and violations

The recent parliamentary elections were marred by Kurdish parties accusing each other of fraud and violations, with some even threatening to reject the results. The vote’s credibility now lies in the ability of the Kurdish region’s Independent High Election and Referendum Commission to carefully investigate each of 1,045 complaints.

Preliminary results showed the KDP with a massive lead, securing 44 seats compared with the PUK’s 21. Gorran had a poor showing, winning just 12 seats, half of what it had won in the last election. The opposition New Generation party took eight seats, the Kurdistan Islamic Group won seven and the Towards Reform alliance earned five.

The KDP continued to count on its strong voter base in Erbil and Duhok, and the party can point to stability and significant achievements under its rule. However, what is lacking is a credible alternative in these provinces to challenge the KDP’s dominance.

The failure of opposition parties to make significant inroads in this election ultimately suggests that the public remains unconvinced they can deliver meaningful change.

Voter turnout

After the elections comes the painful process of forming the Kurdish government. As the post-2013 crisis showed, maintaining stability and harmony in any coalition will be tough. If opposition parties feel marginalised, public protests could erupt and paralyse parliament.

An important indicator of political sentiment is turnout. While higher than in the recent Iraqi elections, voter turnout for the Kurdish parliamentary elections, at around 57 percent, was the lowest of any Kurdish vote since 1991. This might signal public apathy at the prospect of challenging the status quo, along with a perception that the opposition groups are not credible.

The continued lack of consensus between Kurdish parties directly harms their influence in Baghdad. The Kurds have for years been considered kingmakers in Iraqi politics, but their future clout will depend on the unity they can muster.

With independence shelved, the future prosperity and stability of the Kurdish region runs through Baghdad. Without a strong hand in the new government, the Kurds risk diluting their voice - a problematic prospect, considering the number of unresolved issues between Erbil and Baghdad.

Risks of continued rivalry

Issues such as the status of Kirkuk and other disputed territories, the share of the national budget, oil exports, and payment of Peshmerga salaries are largely in the hands of Baghdad. Only a strong, united and determined stance will see Kurds win key concessions.

A continued rivalry between the KDP and PUK not only increases the danger of a return to a dual administration, that emanated from a failed power-sharing agreement in the 1990’s and subsequent civil war in which the region was divided between the PUK centered in Suleimaniya and KDP based in Erbil, but also heightens the risk that rifts will be exploited by Turkey, Iran and other foreign powers.

Their final choice may not be a coalition favoured by the US, but one that can grant Kurds the concessions they desire

Kurdish factions have yet to formally join one of the rival coalitions vying to form the next Iraqi government. Prime minister-designate Adel Abdul Mahdi now has the tough task of bridging fractious political parties to form a cabinet within 30 days of his appointment, and present it to parliament for approval.

The Kurds' hesitancy is owed to intra-Kurdish strife, in addition to unease with Baghdad and their traditional Western allies.

Their final choice may not be a coalition favoured by the US, but one that can grant Kurds the concessions they desire.

- Bashdar Pusho Ismaeel is a writer and analyst whose primary focus and expertise is on Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Middle Eastern current affairs. His work has previously appeared in the BBC World Service, RT, al-Sharq al-Awsat, the Washington Examiner, Rudaw, Kurdistan 24 and the Daily Sabah.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

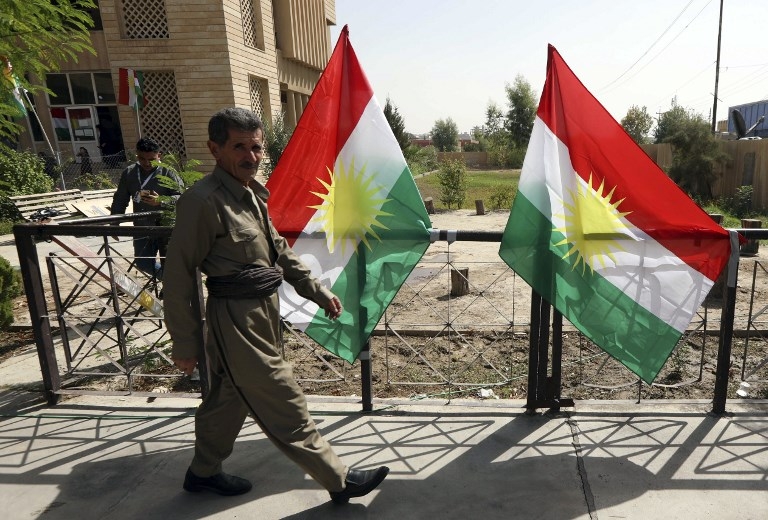

Photo: An Iraqi Kurdish man leaves after casting his ballot for the parliamentary elections in Erbil on 30 September 2018 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].