Khashoggi case highlights challenges for press freedom in Turkey

As news continues to unfold about the alleged murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, one question looms large for his colleagues: if indeed he was killed, why was the consulate in Istanbul chosen as the murder site? Would such an act have been possible at diplomatic missions in the US, UK or France?

Khashoggi had been to Saudi mission offices in the US numerous times previously. Why wasn't he targeted there? If a conspiracy was organised to kill our fellow journalist, did the perpetrators choose Istanbul because they thought they could pay a smaller price for executing their plan there - and what does this say about Turkey's treatment of journalists?

Khashoggi recently told the BBC that he did not see himself as a dissident. "I am just a writer. I want a free environment to write and speak my mind," he said. His writings and his friends' accounts of him support this statement; however, not being a dissident did not change Khashoggi’s fate.

Falling victim to intolerance

Every sign suggests that Khashoggi fell victim to intolerance. The extent and consequences of intolerance vary according to geography, but its limit-pushing nature never changes.

In the US, who could have imagined a decade ago that a president would demonise the media and speak so recklessly? Was this anti-media attitude echoed in the desert, with US President Donald Trump's hostile stance against his country's media finding a parallel in Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's daring and sometimes deadly moves?

In the simplest terms, journalism is the profession of asking questions. For most journalists in Turkey, asking questions means running the risk of losing their jobs

Remember how kindly bin Salman was welcomed by Trump during his US visit six months ago. "President Trump ... has encouraged the crown prince to believe - wrongly, we trust - that even his most lawless ventures will have the support of the United States," the Washington Post's editorial board wrote in a recent piece about Khashoggi's disappearance.

Turkey is the only real democracy among the Muslim nations in the Middle East, which is a source of pride for everyone living in the country. You do not vanish into thin air when you enter a Turkish consulate anywhere in the world just because you are a government opponent. Under this absurd criterion, the situation in Turkey might not seem that problematic - but in reality, that old malady of intolerance has also been reigning in Turkey, too.

Fear of state reprimands

Our journalist friends in mainstream media outlets have been trying to report the news, while living in fear of potential reprimands from Ankara. News channels have to choose from a pre-filtered list of names when looking for participants to invite on to discussion programmes.

In the simplest terms, journalism is the profession of asking questions. For most journalists in Turkey, asking questions means running the risk of losing their jobs. It has been years since Turkish people last watched a real interview with a leader in charge.

"One who does not take sides will be left out," President Recep Tayyip Erdogan once said in a parliamentary address. This understanding has also become true for the media. Many of our colleagues are struggling to do their jobs, while simultaneously feeling trapped - a stark contrast to the nature of journalism. Some journalists were laid off when the media outlets they were working for were sold; the rest are "stuck between their dignity and the future of their children," as one of our colleagues put it.

Those looking at Turkey from the outside might believe that only one bad thing has happened to press freedom in this country. Yet, the government pressure weighing on Turkish media today is not the first assault on our industry.

There was no press freedom in Turkey before Erdogan. In his early years in power, he had to fight the ruthless oligarchic structure's intolerance of his own values. His government was challenged and his party threatened with closure, but mainstream media never stood by him during these anti-democratic processes.

Continuing intolerance

As power changed hands in Ankara, one might have expected that a government whose members had suffered unjust treatment in the past would not inflict similar suffering on others - but it did not turn out that way. Imposers change, but intolerance continues. The attempted coup in July 2016, and the ensuing crackdown, also created a convenient environment for the government to force media into line.

Nobel Prize winner and French writer Andre Gide once said: "The colour of truth is grey." Nowadays, the colour of truth in Turkey is either black or white. The deep political polarisation forces the country's media to be the voice of one side or the other.

Despite the large number of newspapers and television channels in Turkey, there are principally two basic views: those who applaud everything the government does, and those who criticise everything the government does. Against this backdrop, the sense of truth is collectively sacrificed.

As for those trying to protect their journalistic identities, they may not suffer the same fate as Khashoggi - but it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to survive in this profession, because of intolerance.

- Gurkan Zengin is a freelance journalist based in Istanbul, Turkey. He was the director of news for CNN Turk TV between 2007 and 2009 and the Al Jazeera Turk website between 2011 and 2017. He is the author of several books: Hoca: Davutoglu's effect on Turkish Foreign Policy, Fight: Turkish Foreign Policy during the Arab Spring, and Siege: Turkey's Foreign Policy after the Arab Spring (2013-2017).

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

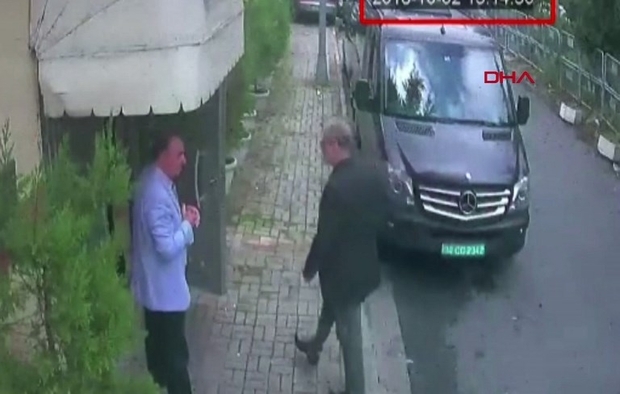

Photo: CCTV footage shows journalist Jamal Khashoggi arriving at the consulate in Istanbul on 2 October 2018 (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].