Stolen childhoods: Gaza's injured children struggle to complete education

GAZA STRIP - For 16-year-old Gaza teenager Abdallah Qassem, getting to school every day is a challenge.

Just a few months ago, it would take him only 15 minutes to walk to the Julis public high school. But after losing both of his legs during the Great March Return protests, he is now confined to a wheelchair, making the journey much more complicated.

Qassem lives in Gaza's Sheikh Redwan neighbourhood in an apartment situated on the second floor. With a small entrance and no ramps to accommodate Qassem's wheelchair, he has to be carried down the narrow stairwell by his two older brothers.

The road to school is sandy and unpaved, making it both difficult and dangerous for Qassem to navigate his way there.

After leaving his home, his brothers carry him to an awaiting taxi and place him inside. Once he arrives at school, the driver lifts him out and puts him back in his wheelchair from where he can make his own way to his lessons.

On the days Qassem does make it to school, he can only attend his first three classes as he then must rush off to his physical therapy sessions.

I have always dreamed of studying electronic engineering, but with my new condition, I am no longer sure how life will be

– Abdullah Qassem, 16

"I have always dreamed of studying electronic engineering, but with my new condition, I am no longer sure how life will be," Qassem tells MEE. "However, with the support of my family, I hope I can get through this stage."

To compensate for the English and maths lessons that he misses at school, Qassem receives private lessons with a tutor twice a week that help to some degree, but the sessions are never enough for him to fully catch up with his classmates.

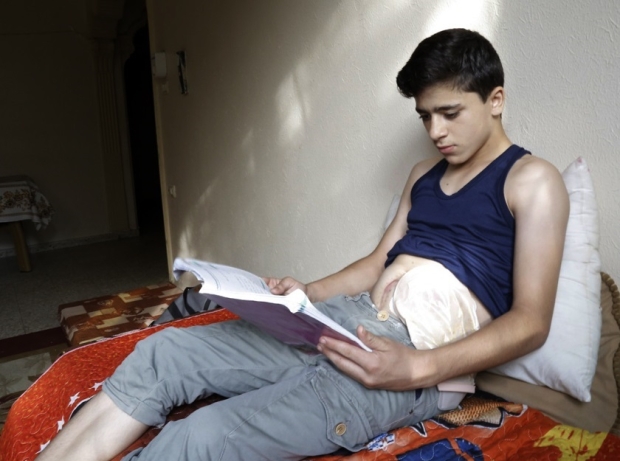

Last month, Qassem had to miss mid-term exams after he underwent surgery on 24 October to stabilise leg bones that were beginning to protrude from his injury. In addition to a week-long hospitalisation, he is now at home still recuperating from the operation and will not be able to attend school until he has fully recovered.

'Unlivable' Gaza

The Gaza Strip, which has been under a suffocating Israeli blockade since 2007, suffers from sub-standard infrastructure such as unpaved roads and lacks any kind of public transport system, let alone one that is wheelchair-accessible.

These conditions make it difficult enough for people who are not physically challenged to get across the Strip; for those in a wheelchair, it is a feat. Ramps, lifts and accessible toilets are rarely seen in the impoverished Strip.

Suddenly, I was shot in my right leg and [then] the bullet went into my left leg

– Abdullah Qassem, 16

In July 2017, a United Nations report revealed that the living conditions of nearly two million residents - including 1.3 million refugees - are dramatically worsening and the Strip has become "unlivable".

Mostasem al-Minawi, international public relations director at the Ministry of Education (MOE), says that resources are very limited.

"Due to the current political situation and the siege imposed on the Gaza Strip, this has reduced MOE's resources. Making public schools accessible requires great financial resources, which MOE does not have due to the lack of funds. A few measures are carried out by NGOs to improve the situation, but this is not enough."

Tensions have worsened in Gaza since 30 March when Israel met largely peaceful mass protests near the fence separating Israel from Gaza with lethal force. According to the Palestinian Ministry of Health in Gaza, more than 210 Palestinians have been killed, with 19 percent of them being children. One Israeli soldier was killed during the same period.

Around 10,000 Palestinians have been injured during protests, including more than 1,800 children. According to al-Minawi, 210 of these children are registered in Gaza's public schools and 92 of them have stopped going to school completely or are missing many classes due to their injuries.

"I was watching how eager the protesters were to remove any barrier [the barbed wire fence] to our occupied land. Suddenly, I was shot in my right leg and the bullet went into my left leg," he says.

Qassem was taken to al-Shifa, Gaza's largest public hospital, which was overwhelmed with casualties from the protest that day. He had to wait until 10pm to get urgent surgery after having lost much blood. Later, he had to endure two more operations, with the final one ending with the amputation of both of his legs.

Qassem needs extensive physical therapy for six months, and after this he should be ready to be fitted with artificial limbs.

Qassem comes from a modest family that was already struggling financially before his injury. His father, who is the sole breadwinner, works in the archives department at the Ministry of Health (MOH) and receives a monthly salary of $400.

Before Qassem's injury, the family's money barely covered basic needs and now their expenses have doubled. Due to a shortage of medical supplies in public hospitals, Qassem's family has had to bear the cost of medications such as antibiotics and pain-killers, which cost from $30- $50 every two weeks.

In addition to private tutoring, Qassem needs the taxi to transport him back and forth from school and to physical therapy sessions three times a week.

According to the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor, 38.8 percent of Gaza residents are stuck below the poverty line as a result of the Israeli blockade, while a staggering 45 percent of people in Gaza are unemployed.

'We were peaceful'

On 8 June, 15-year-old Waseem Mahmoud was watching dancers perform dabke, a traditional Levantine line dance, in what residents call "tent city," in the Abu Safiya district of Jabalya, north of the Strip.

As he was enjoying the performance, Mahmoud says he suddenly felt as though his right leg could no longer carry him and he found himself collapsing to the ground. He had been shot by an Israeli sniper.

“We were peaceful. We did not constitute any danger," says Mahmoud. "That moment changed my life."

Mahmoud is in the ninth grade at the al-Baneen public school, north of the Gaza Strip. With his school just a kilometre from his home, he would walk to classes every day. But after doctors put metal rods in his legs, he says it is still too painful to walk on crutches.

"I want to go to school, but my injury makes it difficult for me," Mahmoud says. "My mother helps me study at home."

Dreams of returning home

It was 30 March, the first day of the protests, when Israeli forces shot Arafat Harb in his abdomen while he was in Gaza's Abu Safiya area.

The 15-year-old had managed to cross through the barbed wire fence separating Israel and Gaza after other protesters had removed parts of it. He was on the Israeli side of the fence when he was injured.

"I have always dreamed of going back to our occupied land. This is why I had the courage to pass through the barbed wire fence. I was not afraid at all," he says. "I stayed there bleeding for almost 15 minutes until one of the medics managed to pull me to the nearest medical point on the Palestinian side," Arafat says.

His father's medical insurance covered part of the travel expenses, but he had to borrow an additional $1,700 in order to be able to pay for the rest of the costs.

I dream of owning my own workshop, but my injury has caused me to lose two academic years

- Arafat Harb, 15

He spent three months in Egypt, where he had two operations, and returned to Gaza in June, where he continues to attend physical therapy sessions. Doctors estimate that it will be at least a year before his bones heal and he fully recovers.

Arafat is in the 10th grade at the al-Taqwa public high school in the west of Gaza city. He lives with his parents and eight siblings in Gaza's Sheikh Radwan district.

Although Arafat has gone from using a wheelchair to using crutches, his body is still weak. And because his home is on the fourth floor of a building, his mobility is limited.

Due to his injury, he has not been able to attend his classes at all since the beginning of the school year. He also missed last year's exams.

Arafat dreams of becoming a carpenter and completing education at a vocational school.

"I dream of owning my own workshop, but my injury has caused me to lose two academic years," he says.

'In honour of his father'

In 2004, Mohamed Sarsour's father was killed by an Israeli air strike. In the 2014 Israeli war on Gaza, his family home was bombed by Israeli forces.

On 8 June, while chanting in Malaka square for the Palestinian right to return to their land, he was shot in the lower abdomen.

I want to be a doctor. I know that I will face difficulties due to my injury, but it will not stop me

- Mohamed Sarsour, 14

"Mohamed still has shrapnel in the lower part of his spine that causes him pain. He cannot sit on a chair for long hours," says Ameera Sarsour, Mohamed's mother. "The doctors said that if they moved it, there might be negative consequences leading to permanent disability."

Despite the challenges, Mohamed's mother tries to encourage him to attend his grade nine classes at Dar al-Arqam school, in the al-Sha'af area east of Gaza. But due to the pain he experiences after sitting in a chair for hours, it is not that simple.

Though he can walk and does not need a wheelchair, he is still not able to run or carry heavy objects, and sometimes he gets infections. Additionally, Mohamed must miss school twice a week to go to his therapy sessions.

"I want to be a doctor. I know that I will face difficulties due to my injury, but it will not stop me," Mohamed says.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].