Meeting the 'other': A British Jewish actor's search for voices of Palestine-Israel

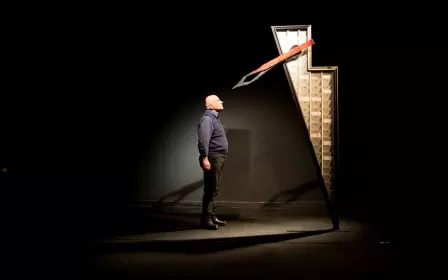

LONDON - Ben Nathan is speaking the words of an Israeli tech engineer who lives near Tel Aviv. He is, in fact, thousands of miles from Israel at a subterranean theatre in London Bridge, The Bunker.

"In my opinion, a Palestinian is someone who doesn't really exist. I call them Arabs because when you say Palestinian, what does that word mean?"

The British-Jewish actor is rehearsing his new play, Semites, alongside British-Jordanian actor Lara Sawalha, speaking words he recorded on a research trip to Israel and Palestine. Sawalha interrupts him, saying: "How can you change reality thinking like that?"

Unsurprisingly, the verbatim testimonies from Israelis and Palestinians which comprise most of the play see the world very differently. Over an hour, the voices we hear explore history - the contrasting view of the events of 1948, for example - as well as the separation wall, the Israeli occupation, and how Israels and Palestinians view the "other" side.

"You occupied our land, you occupied our history, you occupied our future," says Sawalha later in the rehearsal, speaking the words of a Palestinian.

Eighteen months ago, Nathan was in Israel and the occupied West Bank meeting Israelis and Palestinians and recording their testimonies as part of a personal project and quest. The objective was to get past the usual talking points of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and hear stories directly from the people on both sides.

Semites, directed by British theatre maker Daniel Goldman, is the result of that project. The play germinated over several years as Nathan began to question his own long-held beliefs about Israel.All this time I’m very pro-Israel, I defend Israel in spite of lots of things

- Ben Nathan

“I grew up in a household where Israel was always a big feature,” says Nathan. “My parent’s generation were impressionable teenagers around the time of 1967, and from the Jewish-Israeli side that was an incredible victory against the odds. We used to go on holiday a lot to Israel, it is, it was then, a beautiful country.”

The 1967 war saw Israel defeat Egypt and its allies and occupy the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank, Golan Heights and East Jerusalem, a territorial expansion never recognised by the international community or the Palestinians. Israel's victory also paved the way to its sweeping illegal settlement programmes in the West Bank.

A turning point

Post-2000, Nathan says more dissenting voices started to challenge his image of the country, coinciding with Israel’s construction of the separation wall, which started in 2002 and dramatically changed the lives of many Palestinians, and the premiership of Benjamin Netanyahu. In the play we hear two contrasting views of the wall: the Israeli sees it as a form of security, the Palestinian as a form of imprisonment and humiliation.

It was a turning point. “The Arab actress and one other cast member become quite angry about me and what I said in the discussion.

“It challenged me to confront historical facts and narratives that until that time I haven’t spent much time thinking about.”

The verbatim approach

Nathan, who is tall and quietly self-deprecating, grew up in south London and now lives in Bristol in the south-west of England. There he discovered the Salaam-Shalom organisation, an arts group that focuses on work that aims to bring Jewish and Muslim communities together. They have helped him with Arts Council funding for the research project and the play.

Verbatim for me felt like at least then it will be true, honest, not dramatised, it’s real, authentic

- Ben Nathan

Nathan, who wrote the play in collaboration with Goldman and British Palestinian theatre director Tanushka Marah, decided the best way to approach the issue was to use mostly verbatim testimonies based on the interviews he conducted during his trip, to ensure that the real voices of Israelis and Palestinians were heard. “I’m not a writer, so [I thought] maybe verbatim is the way to do it. And also verbatim for me felt like at least then it will be true, honest, not dramatised, it’s real, authentic.”

In the span of over a month in Israel and Palestine – mainly around Hebron and Beit Jala - he spoke to 45 people, both Israeli and Palestinian.

“I began with friends and family, then I went through organisations that have access to different people from backgrounds and political leanings."

He contacted peace and dialogue groups, including Combatants for Peace, which includes both Israeli military veterans and Palestinian ex-fighters, as well as peace group Roots.

As a Jew who had only ever visited Palestinian tourist areas like Jericho and Bethlehem, he admits he was apprehensive about going to Palestinian Hebron and Beit Jala. “I didn’t know how it was going to be. But I felt so at home there, the hospitality of people was magic, and that was a big deal.

“There was a deep sense from all sides that people were desperate to have their stories heard. I was just performing the role of the interviewer, trying to ask the right questions, trying to listen as much as I could.”

He arrived in April 2017 coinciding with the centenary of the Balfour declaration, when Britain pledged to give part of Palestine to the Jews as a homeland and laid the foundation for a future Israel.

“There were massive posters and graffiti referring to Balfour when I was there; there was a plea by the PA to say to the British government, 'we would like you to make some sort of recognition and apology for promising a homeland for Jews but denying it to the Palestinians who lived there.'

“And a lot of interviews were about the role of the British, not only Balfour but 1947” - the United Nations Partition Plan which backed the division of British mandate Palestine into two states, including Israel, which sparked the war that saw more than 750,000 Palestinians forced out of their homes.

They have not been allowed to go back to their land and have since been fighting for the right to return, affirmed by UN resolution 194.

Since the Great Return March protests started in March, more than 210 Palestinian demonstrators have been killed by Israeli forces, according to the Palestinian Ministry of Health. One Israeli soldier was killed during the same period.

"I know Palestinian rights are not being adhered to and that upsets me," he said. "There is a lot of dehumanisation that happens on the ground: these people live the same lives as you, have the same worries as anyone else."

I know Palestinian rights are not being adhered to and that upsets me

- Ben Nathan

In the play we see Nathan's own journey from his self-questioning to the time he spends in Israel talking to people from both sides, and how at the end he says he now holds two entirely contrasting narratives of history in his mind, holding both to be legitimate.

But he shares the pessimism he heard among peace activists in Israel and Palestine about any political progress or reduction of violence at the current time. "There is a lot of material [in the piece] that is critical of both sides' leaderships, and there is a larger geopolitical need to not solve this conflict, to keep this thing going. There is something else going on in corridors of power that means this needs to carry on."

The listening process

The rehearsals for Semites began recently as a collaboration between two British Jews and two British Arabs. Marah is the dramaturg on the piece, working with director Goldman and actor Sawalha.

At first I was sceptical about a piece that wasn't clearly pro-Palestinian, but the process of making this piece has become a challenging and rewarding exercise in listening

- Tanushka Marah, theatre director

At first Marah, like Sawalha, wasn't sure about working on the piece, but during the process of rehearsal and script work, found it to be a worthwhile attempt to hear the Israeli-Jewish perspective, even if some of the testimonies made for uncomfortable listening.

"At first I was sceptical about a piece that wasn't clearly pro-Palestinian, but the process of making this piece has become a challenging and rewarding exercise in listening," says Marah. "Listening does not need to change our views but it can only be a good way to take tiny steps towards dialogue."

Nathan says that he wanted the team to have an ethnic connection and familiarity with the situation, to complement the authenticity of the verbatim.

“This meant we could play with the sensitivity, or insensitivity of the words, parts of the narrative. It’s actually allowed us to be much freer. We don’t feel like we’re treading on eggshells at all. We need to be able to challenge, probe and explore in an environment we all feel safe in."

Prodding and poking

He is nervous before the opening night, expecting friends and family among the audience and a strong reaction to the piece.

“One of the goals of the show is to prod people and poke them. We don’t want them to go away saying ‘oh yes lovely’, we want them to go ‘fu****g hell’ or that was really distasteful. I think if you do any play on this sort of material people are going to walk out.

The discussion becomes quite Israel bashing, and there’s me and only two other people in the audience who are trying to defend Israel

- Ben Nathan

"I’m ready for that. I’m ready for some difficult conversations after the show.”

Nathan doesn’t expect the piece to change every mind, but he does hope it helps in the process of listening to stories that challenge fixed narratives.

Despite the politically dismal situation on the ground in Palestine, with daily deaths of Palestinians in Gaza at the hands of Israeli forces, on a personal level, he feels he has broken down barriers between himself as a Jew with family in Israel, and Palestinians.

“As for many Jews in this country, some at least, the Palestinian is the 'other.' And so obviously it’s a logical equation by spending time, by living with, by eating with, by drinking with, by sharing a lot of time and moments with Palestinians, they are no longer the 'other.'”

Semites opens at The Bunker at London Bridge on Tuesday 30 October and is also showing at Bristol's The Loco Klub from 6-10 November.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].