Why Khashoggi's murder sparked outrage where countless Saudi crimes did not

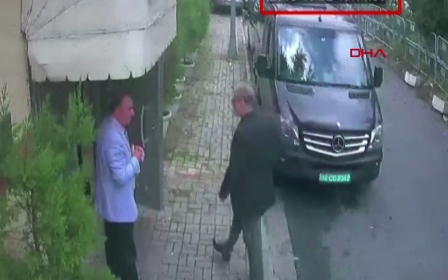

It’s been almost four weeks since Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a columnist at the Washington Post, entered through the main doors of the kingdom’s consulate in Istanbul on 2 October never to be seen again.

We now know for certain that he was killed.

A dangerous precedent

Understandably, his purported death has caused shock and outrage, but also triggered calls from some leading journalists at the Washington Post and New York Times that Western powers take strong action against Riyadh.

Their voices have been amplified by Saudi dissidents and other liberals who have said the kingdom can’t be allowed to get away with his murder, otherwise it would set a dangerous precedent, in which none of us would be safe.

During the past three weeks, I have watched this discussion unfold with much unease. I have thought long and hard about how his story has been played out and pushed at the highest diplomatic levels.

If Khashoggi has been writing for the Saudi Gazette as opposed to the Washington Post would the American media care as much?

It is horrific that Khashoggi was killed for his words. But we also have to face up to the fact that 44 other journalists were killed in 2018. Khashoggi joins a tragic group of 30 journalists who were targeted and murdered with motive.

Only the two American journalists killed by a gunman at Capital Gazette, Maryland, in July received sizeable press. The others, mostly local journalists working in Afghanistan, Mexico or Colombia, have received scant attention.

This week the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) released the impunity index. According to CPJ, at least 324 journalists have been murdered worldwide over the last 10 years, with 85 percent of cases not resulting in a conviction.

"The majority of victims are local journalists. The list includes states where instability caused by conflict and violence by armed groups has fueled impunity, as well as countries where journalists covering corruption, crime, politics, business, and human rights have been targeted and the suspects have the means and influence to circumvent justice through political influence, wealth or intimidation," CPJ said.

I wonder: journalists often talk about being a tribe, of banding together. But if Khashoggi has been writing for the Saudi Gazette as opposed to the Washington Post, would the American media care as much?

Collapse of compassion

Saudi Arabia, together with the United Arab Emirates, has collectively set the Middle East back decades. The kingdom has undermined democratic movements, corrupted the Palestinian cause, funded jihadi mercenaries from Iraq to Nigeria, and murdered thousands of children and civilians in Yemen and left that country in ruins.

All of which makes the campaign to disinvest from the Saudi "Davos in the desert" forum or stop the sale of arms to Mohammed bin Salman, all because of the murder of Khashoggi, quite remarkable.

However most explanations do not stand up to scrutiny. Take Max Fisher’s piece; "How one journalist’s death provoked a backlash that thousands dead in Yemen did not” in the New York Times. Fisher cites the "collapse of compassion" by referring to how a story of one person’s death can sometimes be a lot more powerful than a large statistic.

He uses the story of Alan Kurdi, the boy drowned off the Turkish coast in 2015, and the impact the story had across the globe to illustrate how the amplification of one personal story made it harder for it to be ignored.

What [Max] Fisher doesn’t explain is why the individual stories of Saudis who have been arrested, detained or executed never quite made compelling tales

But what Fisher doesn’t say is that Alan Kurdi’s story was driven by a powerful image of a boy lying face first on the shore; it was the image that communicated the inhumanity of European policy towards refugees and migrants fleeing wars and economic difficulty. No one knew anything about young Kurdi when the image tore at our heart.

It provoked a certain guilt. And frankly speaking, it is nothing other than this guilt that blew up Kurdi’s story. While large stats can be daunting and unfathomable, editorial decisions are often made to keep stories that way. An unequal valuation of life is the reason why a terror attack in Paris will get more coverage than one in Baghdad.

A frightening and brutal age

Crucially, what Fisher doesn’t explain is why the individual stories of Saudis who have been arrested, detained or executed never quite made compelling tales. Instead, it is Khashoggi’s proximity to the liberal elite as a columnist for the Washington Post that turned his disappearance into an intolerable and unforgivable act that made it go viral in the US and large parts of the English-speaking media and into the corridors of the powerful. Fisher alludes to this proximity as a mere footnote, but this is the crux.

Similarly, consider Evan Hill’s "The new Arab winter" in Slate that offers a scathing riposte of America’s role in the Middle East. Hill says the US "helped nurture a new generation of Mideast dictators, and Jamal Khashoggi’s disappearance is just the latest result". He is right.

After narrating deep-seated US complicity, Hill curiously concludes: "Khashoggi’s disappearance and possible killing is a fork in the road for the West’s relationship with the new Middle East […] impunity for Khashoggi’s killing would usher in a frightening and more brutal age, one in which we would be complicit."

But the frightening and brutal age is already here. Saudi Arabia’s intransigence sits ably within America’s larger foreign policy in the Middle East - be it the quashing of the Arab Spring, collaboration with Israeli crimes, or the war in Yemen - and is precisely how we got here. The obfuscation of Arab dignity is by western design and America’s media have played a central role.

Criticising Saudi Arabia

Consider the sycophantry of NYT’s Thomas Friedman towards MBS as a modern-day reformer and recent revelations that the Washington Post was until a few days ago, publishing writers linked to Saudi lobby firms, for a sense of how this outrage towards Khashoggi’s murder simply doesn’t add up.

Given the wall-to-wall coverage, you would be forgiven for thinking that American mainstream media had only just discovered Saudi Arabia (with a sprinkling of Yemen on the side). This is surely not the way you hold the powerful to account. This is not how you build trust with readers or the larger public.

Perhaps the lesson here is for much of the liberal American press, including The Washington Post and the NYT, to come out and admit that they made a mistake when it came to Saudi Arabia, that for too long they towed the state line when it came to the kingdom.

Perhaps, all of this would make more sense if they committed to listening more instead of deciding to act when it’s too late.

- Azad Essa is a journalist based in New York City. He is currently a visiting Nieman fellow.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A man mourns by a makeshifts memorial made of candles and posters picturing Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi during a gathering outside the Saudi Arabia consulate in Istanbul, on 25 October 2018 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].