Creation and catastrophe: A survivor's review of 1948

I am not neutral on the subject of this documentary; a Palestinian who survived the Nakba never could be. It would be like asking Elie Wiesel to take a neutral stand on the Holocaust.

Of course, there is a difference. But to one who, during many of the formative years of his childhood, heard daily first-person accounts of the premeditated massacres against his kin to drive them out of their homes and farms, the difference is mainly quantitative.

Members of the Jewish militias that participated in the atrocities of the Nakba repeatedly state in the documentary that, even then, they were aware of committing crimes similar to what had been perpetrated against them in Europe. One veteran describes searching Palestinians for valuables that he and his fellow soldiers purloined: "We all were depressed. We simply remembered our own exile."

Victims and perpetrators speak

In 1948: Creation & Catastrophe, Andy Trimlett and Ahlam Muhtaseb offer first-person accounts of survivors, along with commentary from perpetrators of the Nakba. The documentary opens by acknowledging that the Nakba and the establishment of the state of Israel both culminated in 1948, but were rooted in earlier belligerent Zionist settler-colonialism and Palestinian resistance to it.

What right did he, his government, and the British elite have to promise my homeland to the Zionists? Who was this colonialist miscreant to reduce my people to mere 'non-Jewish communities' of Palestine?

The cover photo illustrates how that balance really looked: an aggressively armed Israeli man on one side, and a traditionally attired Palestinian guiding a child on the other. The documentary's attempt to balance these elements favours the belligerent, which was my initial gut-level reservation about the documentary - even though it immediately allows the eloquent Palestinian Nakba witness, Samia Khoury, to detail the legacy of neglect and injustice meted out to Palestinians.

That is reinforced by the wish of a counterpart, Yakov Keller, not to be reminded of 1948.

Like it or not, the historical justification for a Jewish state had little to do with Palestinians. The documentary marshals factual information and historical testimonies to explain the compelling forces across Europe that led to the creation of the Zionist colonial movement, most notably the rampant anti-Semitism throughout Europe, fuelled by the church and Europe's xenophobia.

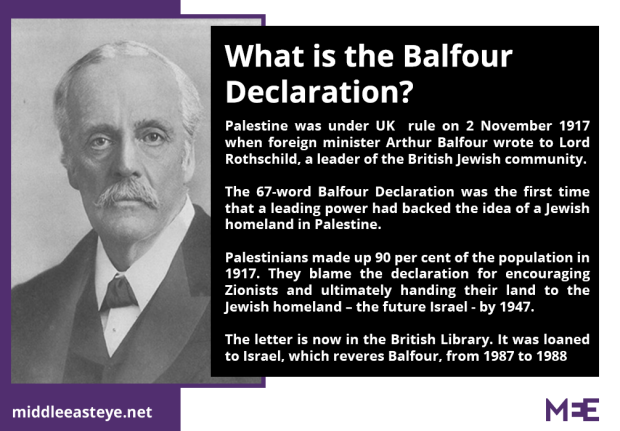

Take a look at the photo of Arthur Balfour in the first few minutes of the documentary. Something about it - perhaps the man's haughty self-assuredness, and the way he seems to look down on me - is intrinsically irritating. What right did he, his government, and the British elite have to promise my homeland to the Zionists? Who was this colonialist miscreant to reduce my people to mere "non-Jewish communities" of Palestine? Had I been born and able to throw a stone in 1936, I would have joined the Great Revolt against him and his Zionist masters.'The war got ugly'

A photograph of Yosef Weitz, the late director of the Jewish National Fund's settlement department, looking bitter and determined, follows soon after - his bitterness born out of his kin's suffering in Europe, while he was determined to exile my people from our homes forever. "The only way is to transfer the Arabs from here to neighbouring countries ... Not a single village or a single tribe must be left," he wrote in 1940, summing up the Zionist leadership's collective plan.

Historians attest to the premeditated nature of the Zionist transfer plan. In 1948, they proceeded to implement it to a T, enacting scores of massacres.

The expertise of the interviewed historians and analysts from both sides of the divide in the documentary is impressive. They delve deep into historical records and relevant documents. Yet, I find it more meaningful to concentrate on some of the silent portraits, many of anonymous individuals who are most likely dead - or, if alive, unaware of the role their silent photos are playing in illuminating my history.

There is the pitiable image of Hava Keller narrating Acre's fall when, to her thinking, "the war got ugly". That ugliness is symbolised by a child having left shoes behind. Keller, then a young soldier, finds the shoes as she enters an abandoned home, and wants to know the child's fate. Keller has a winning sincerity to her concern.

Shortly afterwards, there is an image of a child in Lydda, lost between the soldiers and the crowd of Palestinian civilians they were evicting. We are given a glimpse of that child and a sibling, both hungry and scared. The frightened looks on their faces say it all.The barefoot child of Acre

It dawns on me that it is my late friend, Miriam Petrokowski of Nahariya, whom I see every time Keller shows up onscreen. A friendlier and more sympathetic woman is hard to imagine. I remember Petrokowski in 1982, going door-to-door in her Jewish neighbourhood to collect food and clothing for Palestinian refugees in Israeli-occupied southern Lebanon. Of course, she and her husband played a part in driving them out in 1948, and lived off their colonised fields.

Like my friend, Keller obeys orders: in the documentary, after helping to evacuate Acre of its Arab residents, she moves on to Beersheba to help streamline the expulsion of its natives to Gaza. But her core of decency persists. "Where are they? The Palestinians?" she asks, never forgetting the barefoot child of Acre. She reflects on how, when the war started and the Arabs were driven out, "not one kibbutz said that they don't want to take their land. Everybody was very happy to steal their land."

Benny Morris, an Israeli historian who has documented Israel's war crimes in 1948, says that it was a fatal error to have left any Palestinians in Israel. As the documentary shows a portrait of four generations of Palestinian refugees - there, but for the grace of God, goes my family - Morris identifies them as "the Palestinians that have been fighting us". He justifies Israel's decision to exile Palestinians and kill those who attempted to return to their homes; many returned to collect blankets or food.

"The notion of having this state empty of Arabs was already part of my life," says Israeli historian and veteran Haganah fighter, Mordechai Bar-On. He casually relates an incident in which he shot, point blank, a Palestinian returning to reap the harvest in his field. "I didn't blame myself. I didn't have any feeling of remorse," he declares, smiling. Bar-On prefaces his account with the standard Israeli explanation: "You wanted a war? OK. Now you run away. You'll never come back."

Depopulated villages

Uri Avnery, the famous Israeli activist and founder of the Gush peace movement, states that he obeyed orders and "that was that". But he notes, rather apologetically, that he felt happy when a hunted Palestinian escaped alive over the hills. Seen from a Palestinian's point of view, the difference between his timid acceptance and Morris's impudent justification is academic.

Towards the end of the documentary, the narrative seems rushed: the story of depopulating and erasing more than 500 Palestinian villages, covering them over with parks and new settlements, is compressed into summary statements, albeit powerful ones by the likes of historian Ilan Pappe. This forces the submersion of so many memorable accounts of cruelty, massacres and occasional heroism: Tantura, Lubya, az-Zeeb, al-Bassa, Iqrit and scores more.

I, of course, have an answer - but in the documentary, the question is left hanging.

The focus of 1948: Creation & Catastrophe is more on the Nakba's major events in urban Palestine: Jerusalem, Haifa, Jaffa, Acre, Lydda, Ramla, Nazareth, Beersheba, etc. Yet, in 1948, the majority of Palestinian refugees were driven out of rural communities. For years, the Haganah had gathered detailed intelligence on their demographic, social, geographic and military conditions. Despite their minimal fighting power, such villages resisted expulsion tenaciously.

The next project

They consequently suffered a long list of massacres designed to scare them out of their homes and across the border to neighbouring countries. In Deir Yassin, one of the earliest and vilest massacres, the Irgun and Haganah set a precedent: the village even had a peace treaty with the adjacent Jewish community.

Our elders repeated such accounts in whispers of fear, distrust and secrecy. In his Arabic-language book, Nakba Wabaqaa, Palestinian historian Adel Manna exposed several such massacres committed in my home turf of Galilee, listing names, dates and geographic locations. This scholarly treatise deserves translation to English for a wider readership.

In a similar vein, I hereby recommend to the producers of this documentary a second and parallel project: there is a lot of remaining footage dealing with the Nakba's rural events, which merits a second documentary, perhaps with Manna as the adviser. The Galilee could be its focus, and rural Palestinian women its protagonists. Samia Khoury should narrate - I insist.

- Hatim Kanaaneh is a retired public health physician and a Palestinian citizen of Israel who practiced in rural Galilee, where he founded the Galilee Society for Health Research and Services. In retirement, he published a book of memoirs and a collection of short stories.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Palestinians protest on Nakba Day (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].