For a Palestinian mother in Israeli jail, family life is a faint voice over the airwaves

On my way home, I hear a weary-sounding man call in to a local radio programme. He recounts bitterly and with great discomfort the various ailments gnawing away at his body, listing every operation, check-up, complication and medication, without skipping a single detail. It’s clear that his suffering is a great burden.

The caller is the father of a prisoner from the Gaza Strip serving a life sentence. Despite his ill health, the man cannot visit his son, since Israel’s occupation forces do not issue permits to relatives wishing to visit their children in prison. It clearly pains the caller to go into such detail about his health on public radio, but this is the only way he can let his son know how he is doing.

As I listen to the call, I am reminded of the days when I was a prisoner in the cells of the Israeli occupation, two years ago. One person especially comes to mind: Nisreen Abu Kameel’s dark, calm face, steeped in sorrow.

Listening for the signal

In a few weeks, Nisreen will have served three years in prison, with another three years left before she can return to her family in Gaza.

A mother of seven children and a Gaza resident, Nisreen was arrested at the northern Erez crossing in October 2015 and sentenced to six years in prison. Her family members have been barred from visiting or communicating with her, as they live in an even larger prison: Gaza.

Each afternoon, Nisreen attempts to pick up the signal of the Voice of Prisoners radio station, which broadcasts a programme that families of detainees use to send messages to their imprisoned relatives. They call in to the programme with updates on their lives, providing many inmates with the only available link to their families.

When she hears her husband speak, other inmates congratulate her, and timid signs of joy creep over her tired face

It is only on clear days that the radio broadcast can be picked up. In coastal regions, such as Haifa or Jaffa, where the two women’s prisons are located, weather conditions are often not conducive to a clear signal. Nevertheless, all year round, rain or shine, Nisreen tries to tune in, longing to hear her family. When she hears her husband speak, other inmates congratulate her, and timid signs of joy creep over her tired face.

For the next three years, as has been the case for the past three, Nisreen will continue to hear news of her seven children and husband from a broadcast she can only pick up in clear weather conditions. Israeli occupation forces do not allow female Palestinian prisoners to speak to their families on the telephone, and harsh restrictions are imposed on sending and receiving letters.

Privacy rights quashed

If a detainee wants to send a letter to her family from prison, it must first be scrutinised by prison administrators. The same applies to incoming letters. No consideration is given to the basic human right of privacy, and it takes more than a month for a letter to even reach its recipient - and even then, only if prison intelligence approves of the contents and does not deem it a threat to state security.

The image of Nisreen speaking fondly and longingly of the news shared via radio from her husband and children still clings to my memory. I pity the mother who has to learn of her children growing up through the changes she hears in their voices on the radio, or from the handful of photographs prison administrators permit her to receive every two or three bitter months.

Nisreen also suffers from myriad health problems, including high blood pressure and hyperlipidemia. In addition, her hand was recently fractured, the pain of which was compounded by neglect in her care. She has since been transferred to Hasharon prison for the physiotherapy required to recover normal use of her hand.

Another Palestinian from Gaza recently detained at Erez was 60-year-old Ibtisam Ahmed, who was sentenced to two years in prison. Her family members are not allowed to visit her, so along with Nisreen, she waits for clear weather conditions to hear their voices.

Strictly monitored visits

According to the laws of the Israel Prison Service, families of detainees receive fortnightly visit permits, in coordination with the Red Cross and with the approval of intelligence services. Visits last for 45 minutes, during which families meet in a large room split into two corridors, separated by a soundproof pane of transparent glass. They speak using phone receivers that are monitored by prison administrators.

Strict procedures govern the issuing of visit permits for prisoners deemed to pose a security threat. For six months, I lived in the same room as two women whose families were allowed to visit them only once every three months. This fate is often handed down for no clear reason, beyond a claimed threat to state security.

Mothers are forced to live apart from their children. A female prisoner with a child younger than six is allowed to hug her young child for 10 minutes, once a month

A university student from Bethlehem studying English, Maysoon Mussa, is a kind and calm young woman who loves cats. She told me that she was in charge of caring for 12 cats at home, showing me photographs and telling me about each one. The love in her eyes as she spoke quietly and tenderly was clear; she treasured these photos.

Sentenced to 15 years in prison, Maysoon is one of the many prisoners whose families are only allowed to visit once every three months. Sometimes, there is a delay in the issuance of permits, extending the wait even further. The outcome is that, during the course of her detention, Maysoon will only be allowed to see her mother four times a year from behind a pane of glass.

Oppressive regulations

Israel is currently holding dozens of Palestinian female prisoners in its jails. They survive in extremely trying conditions; some were shot with live bullets at the time of their arrest. One prisoner suffered severe burns affecting 60 percent of her body, while another is pregnant.

Mothers are forced to live apart from their children. A female prisoner with a child younger than six is allowed to hug her young child for 10 minutes, once a month.

Families can bring photographs into the prison once every two months, with a maximum of five photographs at a time. As well as the brutal oppression they face, prisoners must embark on drawn-out battles to claim their right to have their own photograph taken once a year, which would be given to visiting families.

Regulations related to photographs were even more oppressive when I was in prison. I never once saw personal photographs given to families of prisoners in the 10 months I served. It was only after the prisoners exerted considerable pressure that some concessions were made.

The above figures are an attempt to express something that is difficult to explain. The reality is that, time and again, female prisoners are being handed lengthy sentences with impeded access to their families - visits that many view as a lifeline.

- Salam Abu Sharar is a Palestinian pharmacist, activist and blogger.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

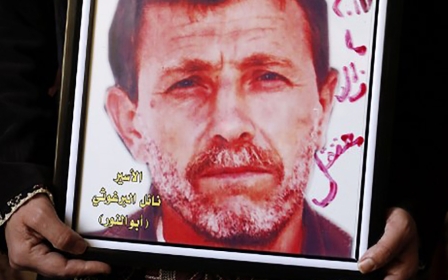

Photo: Prisoners gesture from their cell at Hasharon prison, northeast of Tel Aviv, in 2014 (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].