Unwanted guests: The arts confront Turkey's treatment of Syrian refugees

ISTANBUL, Turkey - One summer evening in 2013, Turkish film director Andac Haznedaroglu was driving in Istanbul when a mother holding her sick child jumped in front of her car.

She found herself helping the woman, a Syrian refugee, and soon her life - and her work as a filmmaker - took a new turn, with the moment later becoming a scene in her movie.

"We went to four different hospitals to get help," she recalls. "That night I realised that all these widespread claims that people were uttering about how the state was taking care of them [refugees] more than its own citizens were all wrong."

Haznedaroglu's Misafir (The Guest) is that rare thing in Turkey, a drama portraying the refugees' stories. Written and directed by Haznedaroglu, the drama talks about the struggle of Lena, a Syrian girl, who loses her parents and crosses the border with her neighbour Maryam.

Turkey hosts the largest refugee population in the world, with more than 3.5 million Syrians seeking a better life after escaping war in their homeland. But Turks have grown increasingly hostile towards people they previously called their "guests".

More than 70 percent of the Turkish people now believe Syrian refugees are taking their jobs, while two-thirds think Syrians are responsible for increasing crime rates, according to a poll conducted by Istanbul Bilgi University’s Centre for Migration Research in 2018.

Humanising the problem

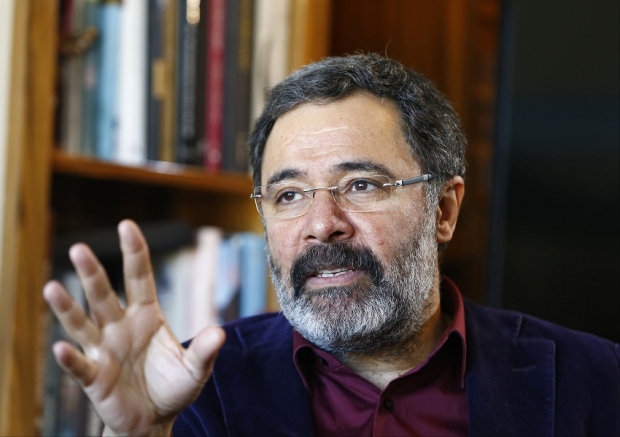

Like Haznedaroglu, best-selling author Ahmet Umit uses his works aim to humanise Syrian refugees and their issues amid the popular backlash against them.

His novel, Scream of the Swallow, is among the first examples of Turkish literature to put the plight of Syrian refugees centre stage.

Part of the book focuses on Nevzat, a police officer trying to solve a series of murders while witnessing the desperate living conditions of Syrian refugees.

At one point Evgenia, his lover, tells him: "You know, swallows are migratory. They fly really fast. So during migration, hundreds of swallows are caught in storms and killed.

"The swallows that do make it scream with anguish and anger as they fly in the sweltering skies of the countries they've arrived in, in remembrance for the friends they've lost en route."

'There is hate towards them, especially among the well-educated, Westernised, and wealthy segments of the society'

- Andac Haznedaroglu

Umit tells MEE: "This is the product of my understanding of what a writer's ethics should be. For me, the primary issue of a writer is to take the side of those who are weak, languishing, oppressed and unprotected."

Haznedaroglu agrees, but adds that her primary motivation was to challenge the negative attitude many in Turkish society have towards Syrian refugees.

"There is hate towards them, especially among the well-educated, Westernised, and wealthy segments of the society," she says. "They are complaining that the Europeans are not coming to Turkey anymore, but only Arabs are. This was my point of departure."

Unfurling the flag

The pinnacle of hostility in Turkey was reached when a group of young Syrian men danced in joy on New Year's Eve in Taksim Square, the heart of Istanbul, unfurling a flag of the Syrian opposition and chanting slogans.

Their joy was short-lived. Angry Turkish Twitter users circulated a video of them dancing in the early hours of 2019: soon 5,000 users were posting the hashtag #ÜlkemdeSuriyeliİstemiyorum ("I don't want Syrians in my country"). The anti-Syrian outrage quickly spread, drawing support from many segments of society.

Since their first arrival in 2011, Syrian refugees have been subject to false rumours and nationwide ire: often they are victims of false news on social media, as MEE has reported, and the subject of fierce discussions.

Umit says that the events on New Year's Eve were perceived as different from previous rifts because this time flags were displayed, which compounding already existing anti-Syrian sentiments.

'In our history, as I mentioned in some of my books, the organisation that is called the state can be very cruel towards others in the name of protecting the homeland and the flag. But to me, the homeland is humanity'

- Ahmet Umit, author

"There was already discontent due to their presence and that of other Arab tourists who come to Istanbul. But on top of this, when flags are opened, it is perceived as a threat, because, in the dominant culture, the homeland perception is limited to the land and flag.

"In our history, as I mentioned in some of my books, the organisation that is called the state can be very cruel towards others in the name of protecting the homeland and the flag. But to me, the homeland is humanity. Without humanity, neither the land nor the flag has a meaning."

Haznedaroglu also believes there is symbolic meaning behind a flag being unfurled that sparked this nationalistic reaction. But, she says, the target of the act was not Turkish society but the international community, which Syrian opposition groups accuse of turning a blind eye to the atrocities they lived through at the hands of the government of Bashar al-Assad.

"The rage of the people who had to flee their homes after losing everything is understandable," she says. "However, it is also a fact that this act fuelled the nationalist feelings of [Turkish] society. We have to think about it and the possible consequences of it.

"When they [Syrians] first came, they were presented to us as guests, but, after seven years, this status is dying out. There are sociological results of this. And my movie is about these results."

In The Guest, most of these forms of exploitation are shown in a way that forces audiences to face the realities of what Syrian refugees have to go through.

"Everything that I showed in my movie is real and actually did happen," says Haznedaroglu. "After that night of desperately searching for a hospital, I lived with the Syrian refugees, I spent two years with them, and I think because of this naked truth the audiences gave a positive reaction to the film.

"I was not expecting this level of interest, but many viewers came to me and told me that they regret not having paid attention to the problems of the Syrian refugees. Some of them took action immediately and began supporting solidarity projects for Syrian refugees."

The exploitation is not fictional

Scream of Swallows asks a question on its cover: "Where is hell if not in the world, which has lost its conscience?". Like The Guest, its narrative does not focus on the politics behind the exodus of the Syrians but instead depicts the hellish difficulties, predicaments and despair that refugees encounter on a daily basis.

Umit hails from the south-eastern Turkish city of Gaziantep, which borders Syria and has historical links to Aleppo. It hosts more than 300,000 Syrians, according to a late 2018 report compiled by the state-run migration authority.

'At the beginning, they were embraced by the society, but in time some of them became subject to cheap labour and child labour, while some fell victim to sexual harassment, forced marriages and other forms of exploitation'

- Ahmet Umit

"At the beginning, they were embraced by society, but in time some of them became subject to cheap labour and child labour, while some fell victim to sexual harassment, forced marriages and other forms of exploitation.

"I talk about some of these in my book. But at the same time, they became more visible, but their culture has been regarded as strange by some segments of society. At the beginning, it was thought that they would return to their country, but later it turned out that they are here to stay," he says.

Umit stresses that for him the humanitarian side of the issue is more important than anything else.

"We can discuss the reasons of the outbreak of the Syrian war, we can discuss the foreign policy mistakes of the Turkish government, but we have to see the humanitarian aspect of the issue. There are more than three million Syrians living in this country, having fled tragedies, and as a writer, I cannot pretend that this tragedy is not taking place," he says.

Umit believes there is still a long way to go to address the Syrian refugee issue. He says it will be considered solved when Syrian-origin writers begin writing in Turkish or Syrian-origin politicians emerge in Turkey.

According to him, novels do not lead to revolutionary changes, but they can contribute to the emergence of a humane outlook. Until then, novels like his will not make tectonic changes in society, he says.

"If we can make our people think that the refugees are humans who lost their loved ones and homes to a war, they have children to care for and that these tragedies can happen to us, too, one day."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].