The crumbling ‘bride of the Med’: Using pencil and paper to preserve Alexandria

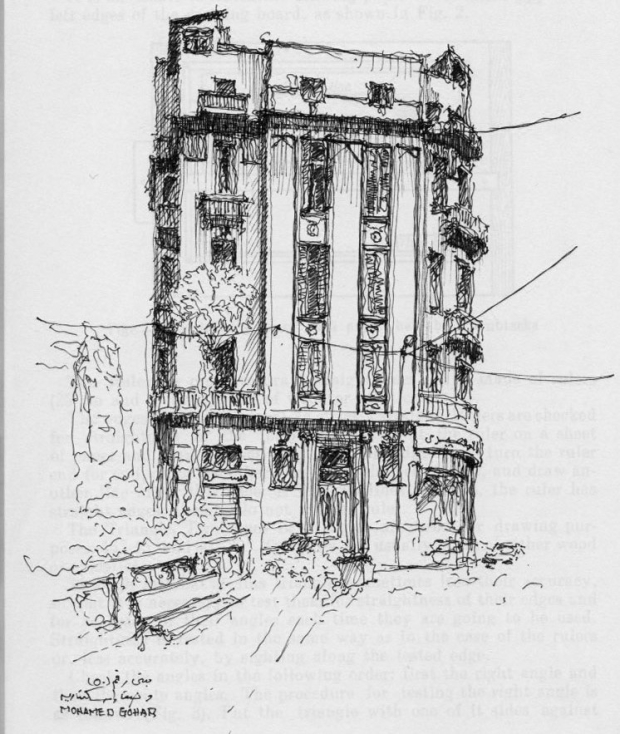

ALEXANDRIA, Egypt - Mohamed Gohar is sitting at a table in an old cafe in downtown Alexandria, doing what he usually does when he has some free time: sketching. Not people or scenery, but Alexandria's historic buildings.

With a Turkish coffee next to his pad, the 35-year-old Egyptian architect says it's more than just a hobby for him.

"It all started about six years ago," Gohar tells Middle East Eye as he finishes a sketch.

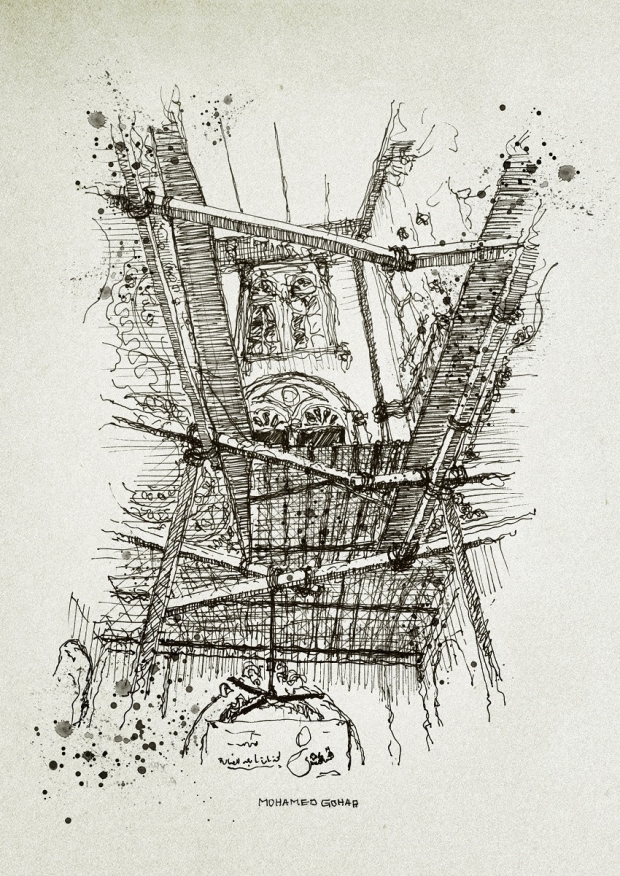

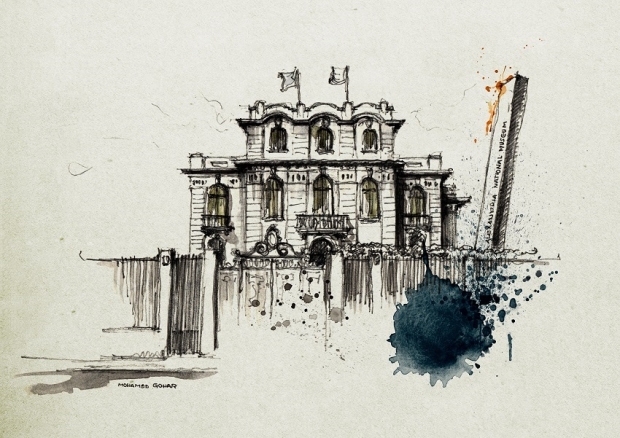

The sketches are part of a project called Description of Alexandria, through which Gohar, who is also a heritage researcher, documents the architectural legacy of Egypt's second-largest city, founded on the shores of the Mediterranean in the fourth century BC.

The architect is not alone in this endeavour. A self-funded cultural and artistic project, Description of Alexandria is carried out by a team of volunteer artists, researchers and architects to raise awareness of the threats posed by the city's rapid and unplanned urban development.

Alexandria's old buildings have, in recent years, been demolished in significant numbers - and many passed away undocumented.

Most recently, in December 2018, a 70-year-old building in the Shatby neighbourhood, where late Egyptian international filmmaker Youssef Chahine once lived, was torn down, stirring a public outcry.

Project members describe the buildings they document and their surroundings, as well as their cultural background, based on the testimony of people who live, or once lived, in the area. This is then published online on the project's Facebook group and blog, as well as in a printed newsletter.

'Every time we lose a building, we lose a part of us'

Gohar says that throughout his work on Description of Alexandria, he has learnt not to get attached to buildings as "we are in a process of constant loss, either by demolishing or abandonment.

"My consolation was that people are the most important assets who built, are building and will build new buildings, cities and memories."

Gohar now sees the deception of this consolation. "I have kept getting attached to buildings as they have embraced our history and memories. I was wrong once more because it seems that every time we lose a building, we lose a part of us; we lose ourselves; and we lose people.

"As an architect, I really got influenced by the loss of specific architectural models that commonly existed in downtown Alexandria and their extension that was built in the 19th century.

Dubbed the "bride of the Mediterranean," Alexandria is about 200km north of Cairo. A popular holiday destination, particularly for Egyptians, it is known for its cultural diversity as well as the dramatic collision of people and architecture that gives it a unique essence. Greeks, Italians, Armenians, Muslims, Christians and Jews all lived here at one point or another.

Its cosmopolitan rich history could always be witnessed in landmarks and buildings, mostly designed by Italians who emigrated to Alexandria in the 19th century, when the port was a major Mediterranean commercial hub.

Bulldozing history and memories

But there are almost no official records documenting all the historical buildings of Alexandria.

"The buildings that were bulldozed disappeared and their history and memories vanished with them," says Gohar. "The demolition of such buildings usually has a negative impact on Alexandrian citizens who grew up in the city seeing them as part of their history.

"The government's Heritage Preservation Committee created a booklet of historical buildings, documenting only about 1,100 buildings. Over 300 of them were later demolished."

Following the 2011 uprising that toppled the regime of long-time dictator Hosni Mubarak, many buildings were demolished in the absence of strict, abiding laws. Four years later, about 27,000 new buildings were constructed on the ruins of old ones.

"This is a great loss of heritage; but it is not the end," Gohar says. "The city is developing constantly; and, if we don't grasp this development, people will normally demolish buildings and construct new ones instead.

"I'm against the demolition of buildings, but if you hear the reasoning behind it, you will find that people have a point, especially in the absence of development plans and proper compensation offered to the owners of these buildings. Such buildings are usually built on lands now worth millions of [Egyptian] pounds."

The future plan for the project, according to Gohar, is to publish a book under the title Description of Alexandria, making public the sketches and information about the buildings.

"Funding remains an object," hearchitect says, and "the project has never received the necessary support from the Egyptian government".

Sitting at the cafe table, though, Gohar is still drawing, preserving in pencil what may be lost to rubble.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

>

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].