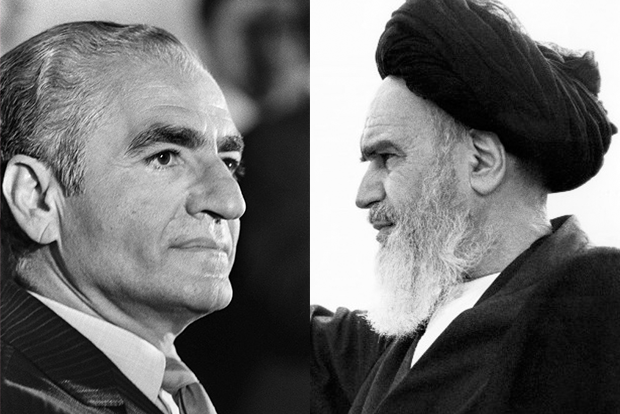

'The Shah is gone': Revisiting the Iranian revolution 40 years later

“Shah raft” (“The Shah is gone”). The same headline on the 16 January 1979 front pages of the Kayhan and Ettela’at newspapers marked the victory of the revolution. Minutes after the public radio announcement of the Shah’s departure, massive and exuberant crowds took to the streets of Tehran. The Pahlavi dynasty had just collapsed and with it, Iran’s imperial regime.

Though seemingly well-known, the history of the Iranian revolution has been distorted by its retrospective reconstruction. Instrumentalised or forgotten, the memories of the 1979 revolution reflect the contemporary positions and agendas of various actors.

The revolutionary ‘surprise’

An unexpected event, the Iranian revolution actually occurred while the Shah’s power was at its peak. US support and oil revenues enabled Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to implement his power politics and project his grandeur.

But after 1975, the sharp drop in oil prices damaged Iran’s budget, and the economic situation deteriorated due to inflation and the regime’s inability to pay back its debts. On the cultural front, the Shah’s Westernisation programme destabilised part of the population. The rupture with conservative values, and the alignment with Western norms, undermined a regime increasingly perceived as disconnected from reality.

Jimmy Carter’s victory in the November 1976 US presidential election promoted a new universalist discourse on human rights. In this novel context, and in order to continue to please its Washington ally, Iran’s imperial regime loosened its totalitarian grip on society. The first consequence was the emergence of critical discourse which, however mild, generated new debates. But most opponents only wanted less repression from the regime and greater independence from the US.

Thinking it could achieve that goal by discrediting the religious establishment, the regime inadvertently created what it sought to avoid. In January 1978, the publication in the pro-Shah daily Ettela’at of an insulting article about Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, then the most influential opposition leader, fuelled the revolution. From that moment on, increasingly large popular demonstrations began. They gradually connected all the opposition groups, while repression simultaneously intensified.

Instead of restoring order, these measures only further motivated his opponents, showing that the imperial regime was in retreat and social change was possible

Facing regime violence, Islamists, liberals and Marxists struck an alliance, issuing a more direct challenge to the imperial government, whose provocations only added fuel to the fire. By the end of the summer of 1978, after several months of mobilisation, the Shah was forced to implement reforms.

Yet, despite his promises to reduce repression and free political prisoners, he had already lost control. Instead of restoring order, these measures only further motivated his opponents, showing that the imperial regime was in retreat and social change was possible.

In September 1978, protesters demanded the Shah’s departure and the return of Khomeini from his French exile. The “Black Friday” massacre on 8 September, terminally discredited Iran’s imperial power: 88 protesters were killed, highlighting the regime’s loss of control.

Countless foreign policy experts and politicians did not foresee the fall of the imperial regime. The most telling example was Carter’s speech in December 1977, where he described Iran as “an island of stability in one of the most troubled areas of the world”.

Islamist revolution or Iranian revolution?

The meaning of the event is open to multiple interpretations, some of which have been superficial. Was the 1979 revolution an Islamist or an Iranian revolution?

To understand its origins, it is necessary to contextualise it. Far from having been conducted solely by a Shia religious establishment, the Iranian revolution originated in protest and opposition movements initiated by intellectual circles after the loosening of the regime’s control of society, starting in 1977.

But the repression of the ensuing demonstrations triggered the revolutionary process. The violence changed the opposition's mindset regarding the imperial regime: Because of its disproportionate use of force, the moderate reforms they had initially demanded became obsolete. That is when the revolution fully became “thinkable” and the coalition between various opposition movements possible.

By combining the defence of traditional values through Shia Islam with the nation’s 'resistance' against a regime viewed as a Western puppet, the clerics successfully became the main and most legitimate opposition force

Those movements united around their common demand: the Shah’s departure. But this unanimity did not amount to a consensual alternative political project. The Islamic religious establishment was split over Khomeini’s vision, while the liberals and Marxists did not agree on Iran’s post-revolutionary future.

Yet all these conflicted revolutionary forces aggregated around several factors. The uprising was rooted in Iran’s religious and national identity. Shia Islam, nationalism and Marxism were the main structuring components of Iran’s counter-society during the last decades of the imperial regime, with influential writings by intellectuals such as Jalal Al-e Ahmad and Ali Shariati.

Among all these eclectic opposition groups, the clergy emerged as the best possible incarnation of a new societal model. By combining the defence of traditional values through Shia Islam with the nation’s “resistance” against a regime viewed as a Western puppet, the clerics successfully became the main and most legitimate opposition force.

The revolutionary spirit would however be short-lived. The initial sense of excitement and optimism rapidly turned into disillusionment as the non-Islamic opposition groups were repressed and progressively eliminated, and the revolutionary utopia itself was quickly sacrificed.

From the revolution to the Islamic Republic

In the months after the toppling of the regime Iran became involved in several conflicts, both domestic and international, that would prove durably destabilising. The revolutionaries themselves entered a period of internal competition, out of which the religious establishment united around Khomeini, who emerged as the sole winner.

In addition to the repression the relationship with the US was radically terminated, as symbolised by the hostage crisis. On the foreign front, the beginning of the Iran-Iraq war in September 1980 rallied the nationalist base of the new regime around the need to ensure the “sacred defence” of the country. Finally the promotion of revolutionary Islam propelled the new regime into a whole new dimension.

Even though the Iran-Iraq war was the main factor that gave the Islamic Republic its rhetoric, the memory of the revolution remains a fundamental element of Iran’s behaviour today.

The instrumentalisation of history by the Islamic Republic has led to a rewrite of the pre-revolutionary period, as well as the 1979 revolution, to its own benefit. Only religious leaders are glorified and presented as those who managed to topple the Shah. Historical narratives have been progressively reorganised around that self-serving discourse.

Despite this hijacking of history, the Iranian revolution remains a crucial 20th-century moment that profoundly transformed numerous regional and world actors.

- Jonathan Piron is a historian and political scientist. As an adviser for Etopia, a Brussels-based research centre, he specialises in social changes in the Middle East, with a focus on the transformative dynamics currently at work in Iran.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi is pictured in 1971, and Ayatollah Khomeini is pictured in 1980 (AFP)

This article was originally published in the Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].