Episodes of oppression: the banning of April 6

Last month, the April 6 Youth Movement was banned in Egypt for allegedly engaging in espionage and defaming the Egyptian state. The informal protest group likely caught the ire of the interim government by actively opposing its actions.

While the group has not kept quiet since the ban, urging the EU to cancel their observation of Egypt’s upcoming presidential election and contemplating actively campaigning against Sisi, the short-term future of open dissent in Egypt is bleaker than ever.

April 6 leaders Ahmed Maher and Mohamed Adel were sentenced to three years in prison in December under last November’s Protest Law which requires, among other things, government approval for gatherings of more than 10 people in a public place. Of course, many countries and international agreements (Article 19(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, for example) recognise reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on free expression.

However, Egypt’s protest law should be, and could be, much more narrowly tailored as to not prohibit peaceful and legitimate political expression - vital for an open and democratic society.

However, the banning of April 6 did not result from the Protest Law. It was instead a result of a lawsuit which alleged the group was guilty of espionage and defaming the Egyptian state. The first charge is a result of an accusation that April 6 received funding from foreign sources. Accusing the movement of receiving foreign funds is not new, and has been refuted in the past.

The second charge is merely a modern equivalent of violating what are called laesa maiestas laws, which unquestionably attempt to limit legitimate political dissent by shielding the state from criticism. Such criticism is necessary for citizens to be able to make decisions on their approval or disapproval of state actions. As such, this is a clear violation of the ICCPR’s Article 19 and the Egyptian constitution’s Article 65 on free expression.

Moreover, April 6’s lawyers claimed they were not notified of the judicial hearing in question, a clear violation of Egypt’s own due process standards, including the constitution’s Article 96 guaranteeing the right of legal self defence. Thus, this ruling is both procedurally and substantively problematic.

The ruling should have been no surprise, however. The banning of April 6 marks only the latest step in the interim government’s oppression of all forms of dissent.

The past 10 months have seen the following episodes of oppression: the violent clearing of the Raba’a and Nahda sit-ins, the imposition of a curfew and a state of emergency, the aforementioned Protest Law and related prosecutions, the raid of Egyptian Centre for Social and Economic Rights, the declaration of the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organization, the Al Jazeera trial, the mass death sentences of suspected Muslim Brotherhood members, the Terrorism Law, and now the banning of April 6. Many commentators have separated these actions into a ‘War on Islamists’.

However, if these twin wars were actually being waged by the interim government, the Tamarod protest movement and the Salafist Nour Party would be been banned and subject to similar state oppression as April 6 and the Muslim Brotherhood, respectively. Instead, both groups have chosen to be at the right hand of the government instead of in its path. As such, it is clear that these actions are part of a singular effort to silence all forms of dissent against the state. There is no ideological focus or reason; the most relevant division in Egypt is between supporters of the autocratic regime and its opponents.

A more nuanced analysis of the progression of the marginalization actions taken by the interim government shows an important trend. The actions begin as mostly executive (the clearing of the sit ins, the state of emergency), transition to legislative (the protest law, the terrorism law), and have now entered a judicial stage (the mass death sentences, the Al Jazeera trials).

While the lack of existence of a legislative branch makes the first transition less institutional than the second, each step is indicative of a further legalization of the authoritarian actions of the regime.

This step-wise process shows that the present interim government is methodically seeking long-term legitimacy by utilising instrumentalities of each constitutional branch of government to meet its ends at silencing dissent. While this does not make the banning of April 6 a necessarily predicable move, it offers contextualisation within a framework which explains the otherwise capricious actions of the interim government.

This legal entrenchment of the authoritarian suppression of dissent will create more generational problems for Egyptian democracy, as now even more laws and legal institutions must be repealed and reformed to allow for institutional democracy to consolidate. In the short term, the upcoming presidential and legislative elections will test first whether the interim government will allow free and fair elections.

They will also show how willing Egyptians are to again risk life and limb to oppose an authoritarian government. The banning of April 6 has shown little reason to hope the interim government has any intention to allow for open and free political debate and little hope that the Egyptian people will be left with political space in which to peacefully dissent.

- Ryan J Suto is an independent analyst on the rule of law in the Middle East.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

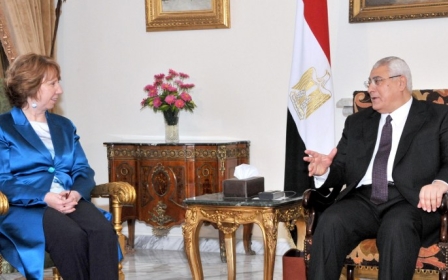

Photo credit: AFP

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].