'Agricultural terrorism': Palestinian crops face destruction by Israeli settlers

HEBRON, occupied West Bank - When 50-year-old Maher Karaje left his home on Tuesday morning to tend to his grape vineyard, as he has done nearly every day for decades, he discovered a graveyard before him.

Hanging only by the trellises that Karaje, his brother, and neighbours had built, were some 450 grapevines with their trunks slashed. It only took four days for the vines, and Karaje's entire livelihood, to dry out.

"I felt like I had lost a child," Karaje told Middle East Eye, standing beneath the now brown and wilted canopy of vines, just off a main highway in the southern West Bank town of Halhoul, north of Hebron.

"These vines were my whole life. I have watered them and taken care of them every day for years, and now it's all gone."

The 22 May attack on Karaje's grapevines came only one week after an eerily similar attack in the nearby village of Beit Einun, where 400 grapevines were cut down, just a few hundred metres away from Karaje's vineyard, which is situated between two major Israeli settlements.

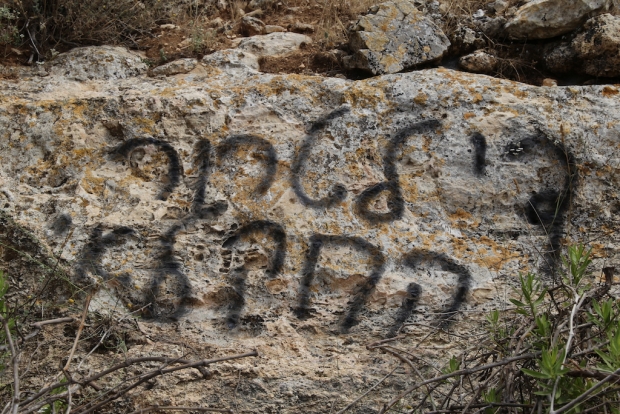

In Beit Einun, a threatening message in Hebrew was graffitied near the destroyed vineyard, saying "We will reach every place". Karaje found a similar message spray-painted on his land.

They cut down the trees just two months before the harvest, which we have been waiting all year for. This year I will lose around 80,000 shekels that I would have made from selling the crops

- Maher Karaje, farmer

"No Palestinian, who understands what this land means to us as a people, would do something like this. This is the work of the settlers, I am sure," he said.

Perched on a large rock overlooking his vineyard, a once picturesque valley of lush green, Karaje picked at the weeds growing beneath his feet, a distraction from the gut-wrenching scene of in front of him.

"Twenty years. Twenty years my brother and I worked on these vines and took care of them as if they were our children," he said, his shoulders hunched over in defeat.

"I dedicated every part of myself to them. To watering them, to making sure the vines grew up straight.

"When they cut these trees, it's like they cut out a part of me with them," he said.

"Now it will cost us somewhere around 200,000 shekels [$56,000] to replace the trellises and rework the land," he said, adding that the destroyed vines would need at least six years to recover.

In addition to the costs of rebuilding the infrastructure of his vineyard, Karaje will soon face even more losses as the start of the grape harvest season approaches.

"They cut down the trees just two months before the harvest, which we have been waiting for all year," Karaje told MEE.

"This year I will lose around 80,000 shekels [$23,000] that I would have made from selling the crops."

Karaje will not suffer the losses alone. The destroyed grapevines, spanning some two acres, or just under a hectare, in size, were the main source of income for his wife and five children.

"We don't just sell the grapes, we sell the vine leaves for cooking, we make grape molasses, jams, and so many other things," Karaje said.

"This is not just a great loss for my family, but for Halhoul as well, and for all Palestinian farmers."

A pointed attack

When passing through the rolling hills of the southern West Bank, dotted with illegal Israeli settlements large and small, travellers are greeted with acres and acres of grape vineyards, a sure indication that one has reached Hebron.

From single vines on the balconies of homes to vineyards that sprawl for kilometres, grapes make up an integral part of the fabric of Hebron, the largest governorate in the West Bank.

Tens of thousands of Palestinians work year-round to cultivate the fruit, which start to bud in the summer months.

The grape harvest in Palestine takes place between August and October, making the attacks on Karaje's land and the vineyard in Beit Einun, just months before the harvest, particularly damaging.

In Hebron, agriculture is the main sector of the economy, with grapes serving as the most highly produced crop.

As of 2013, grapes constituted 36.4 percent of total agricultural land cultivated in the West Bank, with the Hebron governorate serving as the highest producer of the crop, constituting 58 percent of total production, according to the Applied Research Institute Jerusalem (ARIJ).

According to a report from the Palestine Economy Portal, at least 7,500 Palestinian families from Hebron depend on the grape harvest as their main source of income, while annual grape profits in the district reach an estimated $35m per year.

For the past 15 years, Hebron has held an annual grape festival where farmers bring the fruits of their labour to sell and show off in intricate displays.

For Karaje and the 30,000 other residents of Halhoul, one of the largest towns in the West Bank, grape farming is an integral part of the fabric of the community.

"Here in Halhoul, we are famous for grapes and vine leaves," the mayor of Halhoul, Hijazi Mereb, told MEE.

"One cannot imagine how significant grapes are to the people here," Mereb said, adding that around 50 percent of the residents of Halhoul work in the agricultural sector.

Mereb likened the prominence of grapes in Hebron to the olive trees of northern Palestine, which are subject to similar attacks carried out annually by extremist Israeli settlers around the olive harvest, which begins in October.

"We believe that the Israeli settlers intended to carry out this attack at this specific time, right before the harvest was ready," Mereb said.

Shortly after the attack on Karaje's vineyard, Israeli media reported that Israeli police were investigating the incident, along with the previous attack in Beit Einun.

Mereb, however, expressed doubts that anything would come of the investigation.

"We wish that the Israeli authorities will hold the settlers accountable for their crimes and these acts of terrorism, but I'm not so sure that they will," he said.

"My message to the settlers is that even if they cut down our trees, we will replace them, and we will water them and make them grown again with our blood and our souls," Mereb said passionately.

"They could cut our trees every day, but we would never stop growing and cultivating this land. This is our resistance."

'Agricultural terrorism'

Less than 24 hours after the attack on Karaje's vineyard, a cherry grove in a Hebron-area Israeli settlement was burned down by alleged Palestinian attackers, while a Palestinian wheat field was set on fire, allegedly by Israeli settlers, in the Hebron-area village of al-Deirat.

The attack came just as the wheat harvest was beginning.

Found at the scene were threatening messages graffitied in Hebrew, saying "We will reach every place" - similar to the graffiti found in Halhoul and Beit Einun.

According to the Times of Israel, the attackers in the al-Deirat case also graffitied the words "Enough of the agricultural terror", a phrase reportedly used by Israeli farmers to describe attacks on their crops allegedly carried out by Palestinians.

The use of the term by Israeli settlers struck a chord with local Palestinian activist Badee Dweik, 45, who believes the words "agricultural terrorism" should be reserved for the long-standing Israeli settler practice of burning fields and chopping trees belonging to Palestinian farmers.

To me, destroying our crops is just as bad as when they kill us. Grapes mean life here, and when they cut down these trees it's like they take our life from us

- Badee Dweik, activist

"These are massacres, this view you see here can only be described as such," Dweik said as he gestured to the acres of wilted grapevines belonging to Karaje.

Dweik condemned the inaction of the Israeli government when investigating hate crimes against Palestinians, saying that the lack of arrests and punishment of settlers has only helped embolden them.

There have been a spate of so-called "price tag" attacks against Palestinians and their property in recent months, including the torching of a mosque, the slashing of tyres, and graffiti calling for "Death to Arabs", but no arrests have been reported in connection with the attacks.

Though Israeli media has reported the recent attacks on the grapevines and wheat fields as part of the "price tag" movement, Dweik insists that the attacks on agriculture carry a deeper sense of suffering for Palestinians.

"To me, destroying our crops is just as bad as when they kill us. Grapes mean life here, and when they cut down these trees it's like they take our life from us."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.