Anger and mourning in Minya, after another attack on Egypt's Christians

MINYA, Egypt - When they started setting out the chairs at the local cafe on a side street in the Egyptian town of Minya, the plan was to host the fans of football giants Al-Ahly expected to gather on Friday night for a major game against Tunisian rivals.

But when those seats were filled earlier than expected, by 1pm, they instead bore the weight of mourners filing in to grieve five members of the Youssef family, killed when church buses were attacked on the road to the monastery of St Samuel the Confessor.

The buses were returning from the monastery, where they had carried families to pray, mingle and shop, when armed men opened fire, injuring passengers of the first two buses, which escaped, but stopping the third, Anba Makarios, a Minya bishop told Middle East Eye.

The attack, which killed seven and injured 18, was later claimed by the Islamic State group, which in May last year killed 28 Coptic Christians from the same community, on the same route.

The attack has thrown Minya once again into grief and anger, and Egypt has responded by deploying hundreds of riot police to shut down dissent that has reared its head outside hospitals and in churches over the past day.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"Either we avenge them or die like them," hundreds of the city's youth bellowed as they marched towards the railway, blocking it to cut off trips between Cairo and Upper Egypt.

"Where were the police and the intelligence apparatus?" Alfouns Saed, 26, a banker, told Middle East Eye. "The terrorists had their fun with the martyrs. They stopped the bus and took the passengers' mobile phones then went inside and shot them."

Saed was one of the first eyewitnesses to arrive at the scene in a car carrying Coptic clerics and bishops.

"The bodies stayed in the sun for an hour-and-a-half until the first ambulance arrived."

From the hospital those seven bodies were eventually delivered to, a heavily armed escort guided all but one to the Prince Tadros Church, where funerals for the victims were held. Inside, as the bodies were laid on the altar, female relatives collapsed in front of the coffins, and bishops tried to control the simmering anger of youth raising chants against the state.

Outside, plain-clothed policemen trying to enter the church were repelled by mourners. Informants and low-ranking policemen prevented photographers from taking pictures, asking journalists for identification cards.

"The police and the security forces obviously fell short in securing the same site of an attack in the same style against church buses," said Remon, one of the mourners at a mass in the church, angered by how their community had been attacked on the same route twice.

"Do we have to be diplomats or foreigners in order for police to secure the buildings?" he said.

The anger of Minya's youth was heard on the same day when the country was being bombarded with a state-sponsored message about the role of youth in Egypt's message, conveyed through sermons assigned to the country's preachers for Friday prayers and as President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi attended the World Youth Forum hosted in resort city Sharm el-Sheikh.

That message was not diluted on Egyptian media by the tragedy that rocked Minya's community, a point not missed by one Coptic cleric, who asked not to be named.

"I saw all TV channels airing the [al-Ahly] match and the youth conference, but nobody broadcast the tragedy that happened. When they did, all stations made excuses for the police, saying that the buses 'took a side road not the main only leading to the monastery'," the cleric told MEE.

"We have been arranging these trips since the beginning of the year, and have been constantly asking for the buses to be escorted, even by a small police car."

The atmosphere was different at the Anglican church, where the funeral for the only of the victims who was not Coptic, Assad Farouk Labib, was held.

A more restrained mood and smaller congregation meant members of parliament and state and security officials could join the mass but frustration still loomed, especially about how Minya has become a focus for sectarian mobs targeting Egypt's Christian community.

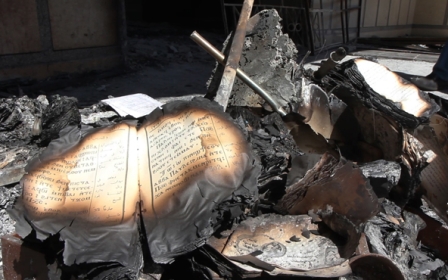

Abanoub Hany, who works as a driver, said the state "comes and cry with us when the terrorists attack us". In contrast, he accused them of turning a blind eye "when Salafists and radicals burn Coptic houses, churches and buildings affiliated with churches."

Amid the anger - the chants, sit-ins and stand-offs with police - there was also more sombre grief, as some of the mourners tried to remember the dead.

Inside the Coptic Prince Tadros Church, Samir Makary was one of a line of men sitting in their jalabiyas, part of the traditional dress code for the men of Upper Egypt.

He came to remember Nady Youssef Shehata.

"May he rest in peace. He was always a helpful hand to all people and was a pure soul, who loved everyone."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.