Covid-19 vaccine: How the poor in the Middle East are being left behind

Several North African and Middle East countries are receiving Covid-19 vaccines at such a slow pace that it could lead to protracted public health crises, global inequality campaigners and health experts have told Middle East Eye.

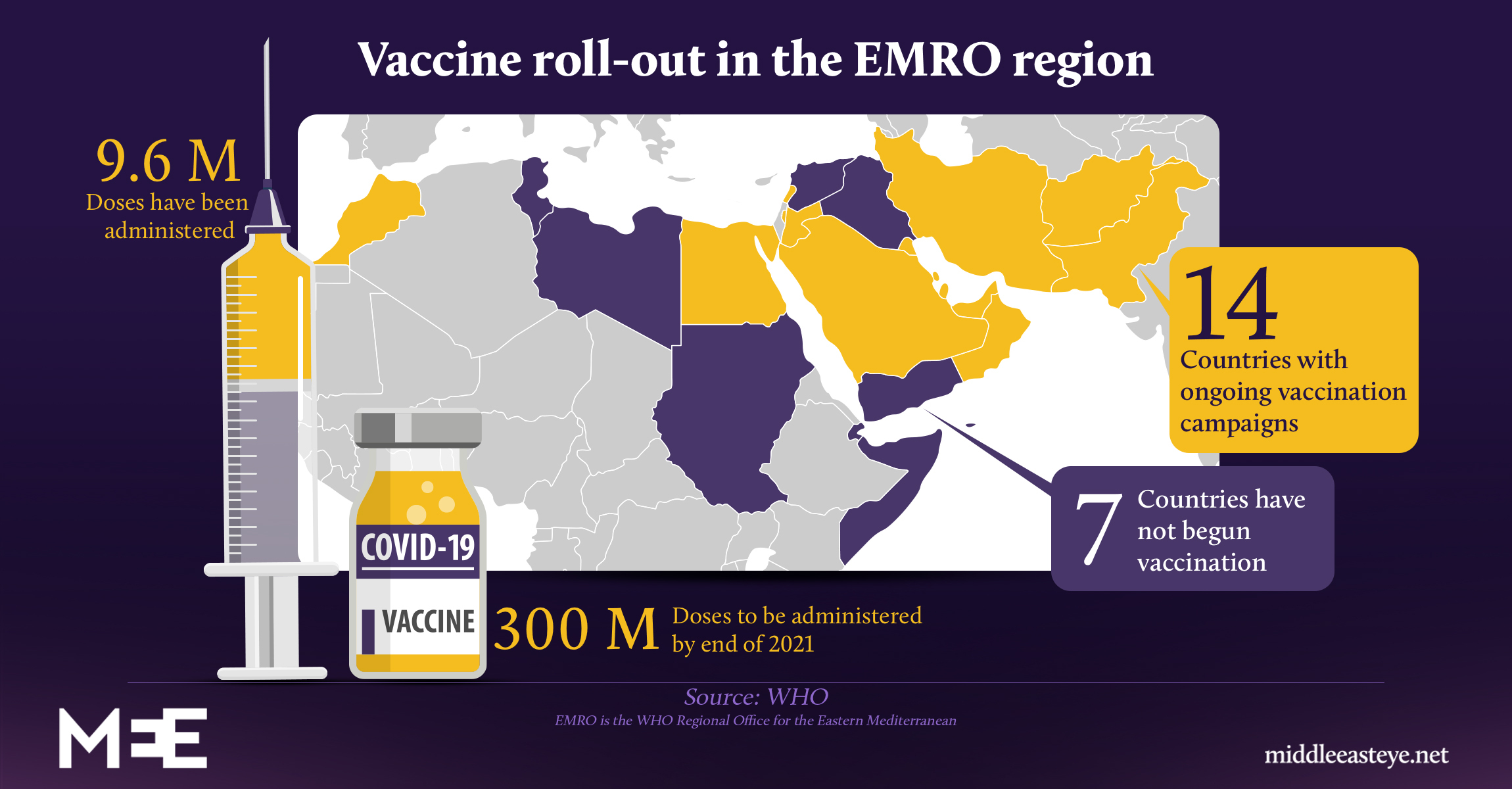

According to World Health Organisation (WHO) data obtained by MEE, only 14 out of 21 countries in the Eastern Mediterranean region (EMRO), which extends from Morocco to Afghanistan - but excludes Algeria and Israel - have received vaccines, amounting to little more than one percent of the population of the entire region.

Amgad El-Kholy, an epidemiologist at the WHO regional office for the Eastern Mediterranean, said wealthy nations were racing ahead of poorer ones to immunise their citizens, illustrating the inequities of the global rollout of vaccines.

"We are seeing [an] unequal distribution of vaccine rollouts around the world," El-Kholy told MEE.

"This has never been more critical than in our region, where health workers are a rare and valuable resource and vulnerable people should be the first to receive support, rather than be left behind."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

El-Kholy's comments come just days after WHO expert Mark Ryan said that 80 percent of all global vaccines had been administered in just 10 countries.

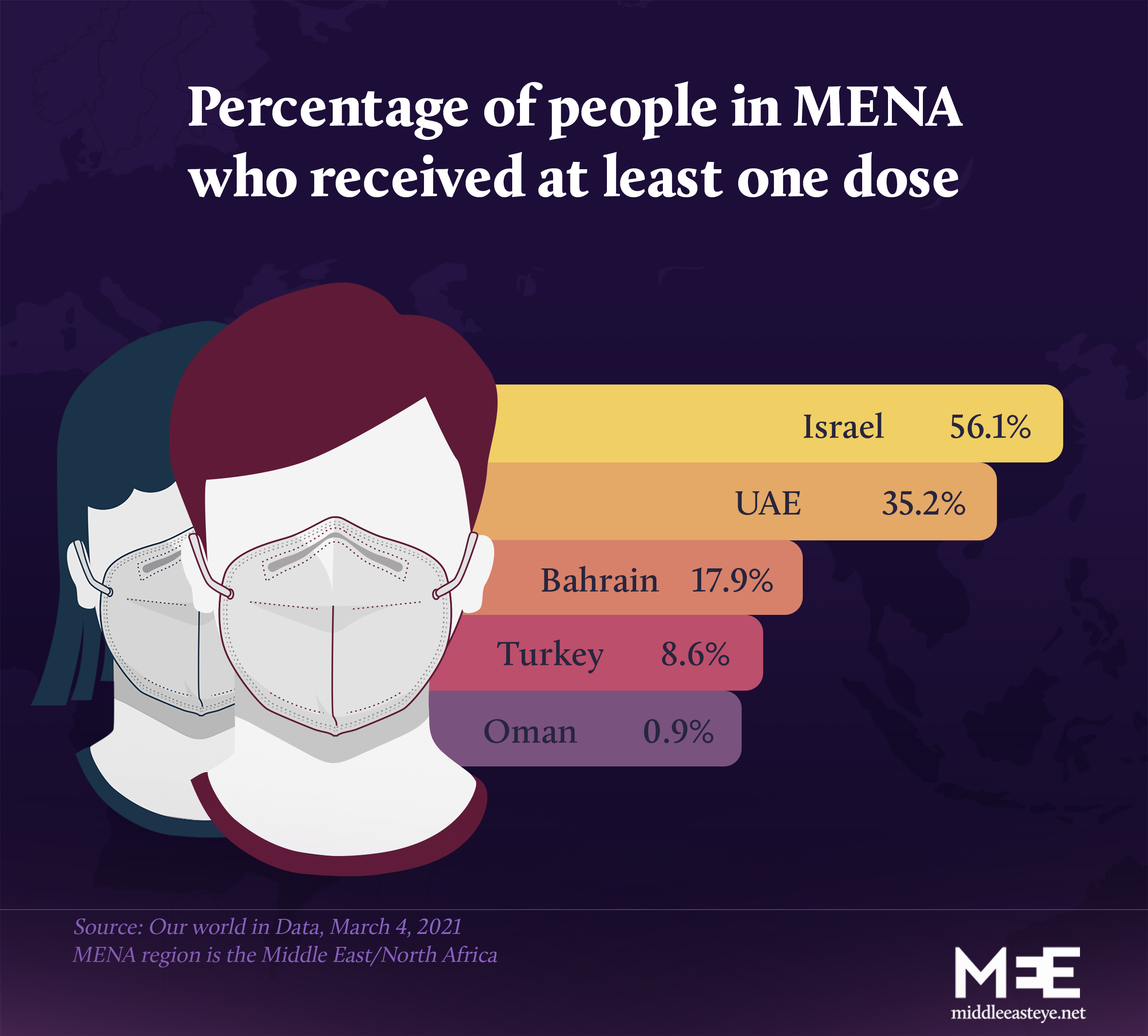

The starkest illustrations of vaccine inequality were evident in the Middle East where countries such as Qatar, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates were inoculating nationals and foreign workers at a frenetic pace while countries like Yemen lag behind.

In Israel, where close to 60 percent of the population have been vaccinated, Palestinians living under occupation have been told they could have to wait months before receiving doses.

As Israelis prepare for a return to indoor dining, hospitals in the occupied Palestinian territories are inundated with patients.

But for a virus that has killed more than 2.5 million people worldwide and devastated livelihoods and entire economies, campaigners say it is the systematic dereliction of political leadership at the highest level that is triggering this threat to global public health.

"It is vaccine apartheid," Anna Marriott, health policy advisor for Oxfam, told MEE. "There is no other way of describing it."

"If you think of the promises that were made at the beginning of the pandemic, that the vaccine would be a global public good - our leaders have failed," Marriott added.

Access to the vaccine has primarily been subject to the wealth of nations or via bilateral agreements with other countries or with manufacturers or from donations - acts which are being described as "vaccine-diplomacy".

Experts say the lack of coordination and transparency has precipitated a series of secret deals that do little to assuage the gaping holes in information world bodies need to monitor the pandemic.

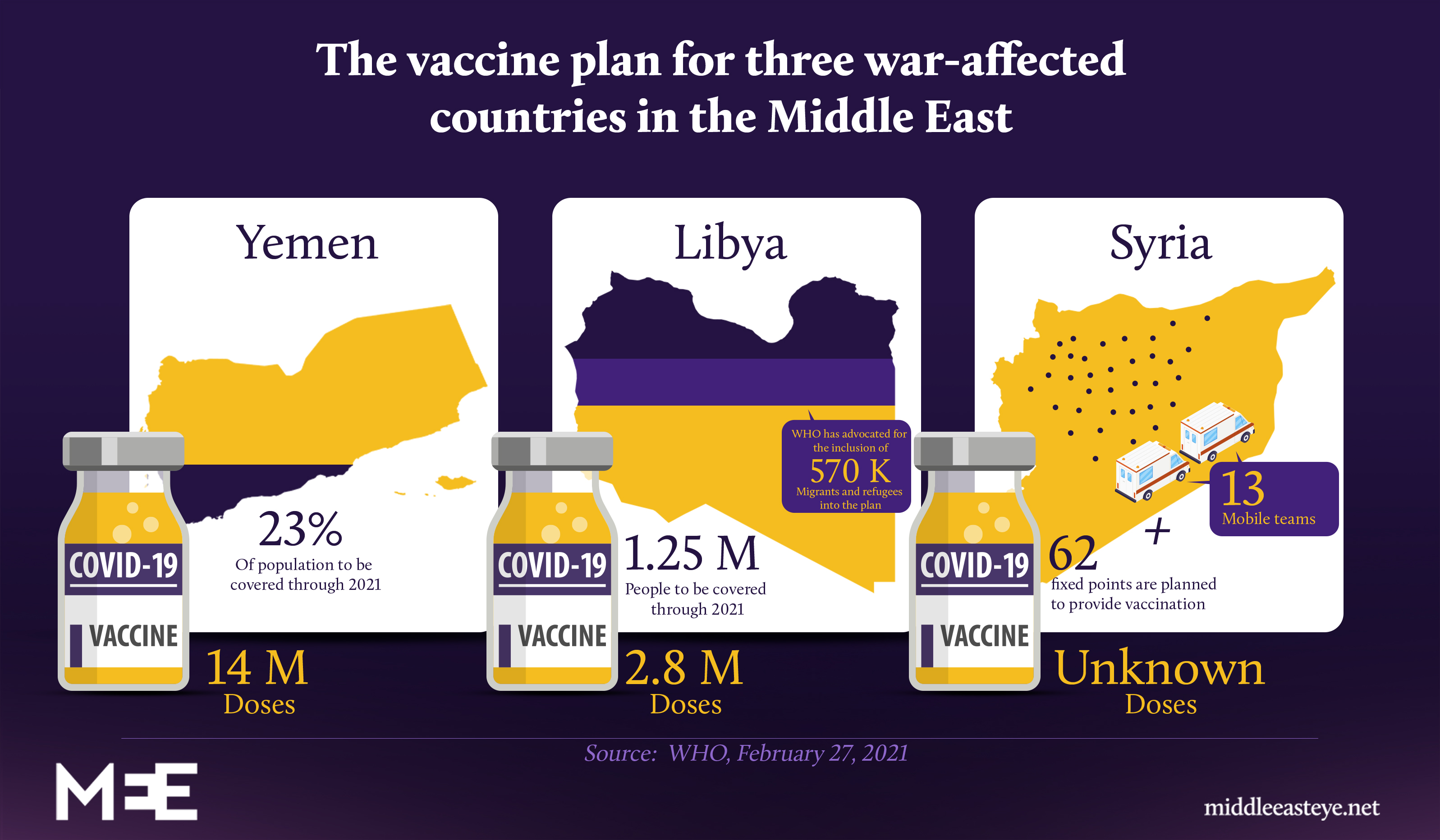

Last week, the Syrian government said it received vaccines from a "friendly country". It's unclear which vaccines they received or how many people are scheduled to be inoculated - necessary data required to handle a global pandemic.

MEE reached out to the WHO for comment on the Syria case but did not receive a response.

Likewise, Tunisia, Iraq, and Egypt received Covid-19 vaccines as donations from China. In these cases, very little is known about the expectations tied to the donated vaccines.

In Egypt, authorities announced last week that it would cost $12 for two doses of one of the vaccines it secured, a move likely to deter the poor - already dealing with strained economic conditions - to seek out a vaccine.

Health experts have been warning since February that the move could precipitate a third wave of Covid-19 in Egypt.

Global public health experts have also repeatedly warned that delaying vaccines will allow the virus opportunity to mutate, potentially undermining available vaccines and ultimately global recovery.

In an attempt to seek a more equitable rollout of the vaccine, GAVI, an international and private organisation that looks to improve access to vaccines, along with a number of organisations including the WHO, formed a coalition called Covax to facilitate the delivery of vaccines to those who cannot afford them.

According to GAVI, $6.2bn has been pledged for vaccines to reach 92 low- and middle-income economies that signed up for the scheme.

Yemen, Syria, the occupied West Bank, and the Gaza Strip, among others, are eligible for assistance through the plan.

But Libya and Lebanon - despite being hit hard by war or, in Lebanon's case, an economic crisis - are regarded as medium to high-income countries and considered "self-financed".

Lebanon's vaccine rollout began in mid-February through a programme initiated by the World Bank, but human rights experts say they are sceptical the country has the infrastructure to achieve its stated goal of vaccinating 80 percent of its population by the end of 2021.

Lebanon is home to the highest number of Syrian refugees per capita, as well as hundreds of thousands of migrant workers who have been left vulnerable by the economic collapse in the country.

As the experience in the US has demonstrated, the availability of vaccines does not always translate to access for its most at-risk populations.

Poor nations will have to wait until 2022

In war-affected countries or those struggling with high levels of corruption, battered health systems and a lack of accountability mean there is no guarantee that the slow trickle of vaccines will end up with those who need them most: health care professionals, essential workers and the elderly.

In the occupied Palestinian territories, where Covid-19 cases are rising, the Palestinian Authority was forced to admit to prioritising 10 percent of the Russian vaccines meant exclusively for health workers to VIPs. In the UAE, the rich and famous were doling out vaccines to their non-resident business tycoons, the Financial Times reported.

"People with connections came here and got vaccines that were provided on a 'friends and family' basis," the FT quoted an unnamed investor as saying.

"Sheikhs have [access to] their own stashes - it's all around the majlis for jabs," he added.

In neighbouring Yemen, however, the situation is very different. No more than half of the country's medical facilities are functioning.

In mid-2020, it was reported that there were fewer than 10 medics for every 10,000 people.

"Covid-19 shook countries with advanced health systems and services. What will it do to a country like Yemen that has lived in the shadow of war for five years?" said Nahla Arishi, a Yemeni paediatrician in Aden.

But even as Covax has begun rolling out vaccines to those countries in need, including several African countries over the past week, global campaigners say donations alone are not going to cut it.

"Without Covax, most countries – from the wealthiest to the poorest – have little hope of getting rapid access to doses of a safe and effective Covid-19 vaccine as soon as one becomes available," a spokesperson from GAVI told MEE.

While the US is rolling out an average of two million vaccine doses per day, with the Biden administration promising to vaccinate all Americans by the end of May 2021, the WHO expects only 20 percent of the entire EMRO region, extending from Morocco to Afghanistan, to have been vaccinated by the end of 2021.

Other experts estimate that low-income countries will experience wide access after 2022.

"We understand that every government and leadership worldwide are keen on vaccinating their people. However, we reiterate that wider is wiser, meaning that introducing the vaccines to the priority categories in all countries is much better than vaccinating all people in a few countries," El-Kholy said.

Waiving intellectual rights

Over the past month, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) has resisted campaigners' demands to have the international body temporarily waive intellectual property rights for those technologies needed to address Covid-19.

Though incoming WTO head Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala of Nigeria has already called disparities in vaccine rates between the rich and the poor "unconscionable", the prospects of a waiver are unlikely with the United States and other western countries opposing the idea.

The deadlock to the proposal put forward by South Africa and India and endorsed by 100 other countries prompted global campaigners to describe the global elite as patronising the poor.

"There are solutions on the table which rich countries are standing in the way of. They need to support the TRIPS (intellectual property) waiver from developing countries and unlocking the supply of the vaccines is the only route to redressing this apartheid situation," Marriot from Oxfam said.

The US in particular has come in for specific criticism. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the administration was re-establishing the country as "a global health leader".

But campaigners point out that while Washington has donated $4bn to the Covax fund - more than any other nation - it has undermined the attempt to accelerate the vaccine rollout elsewhere.

Not only is the US among the most vehement opponents to waiving intellectual property rights, but it has also purchased a further 200 million vaccines for its own citizens, effectively pushing poorer countries and vulnerable populations to the back of the queue. The additional purchasing of Pfizer vaccines will also result in a shortage of raw materials elsewhere, WHO officials have warned.

US lawmaker Ilhan Omar told MEE that the US should be instead "ensuring the broadest possible distribution of the vaccine".

"Letting people in the global South wait years for the vaccine is a policy choice, and [they] don't have to make it. Until everyone is safe from the virus, no one is," Omar said.

In response to the criticism, a State Department official told MEE that the US had "invested aggressively to rapidly develop Covid-19 vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics and to expand domestic manufacturing capacity to bring safe and effective medical countermeasures to market as quickly as possible".

Earlier in February, a group of economists studied 35 industries in 65 countries and concluded that the global economic cost of developing countries not vaccinating any of their citizens would be around $9 trillion.

If developing countries only manage to vaccinate half their population by half the year, the global economic cost would be around US$4 trillion.

In Sudan, where some Covax vaccines have arrived but have not yet been rolled out, the plan is to administer vaccines to one in five by September. In Yemen, one in four are likely to have the vaccine by the end of 2021.

"In either case, half of the cost is borne by developed countries. This is GDP cost so hard to convert it to specific countries or citizens," Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, an author of the report and a professor of economics at the University of Maryland, told MEE.

El-Kholy, from the WHO, agrees: "The global economy cannot recover if there are disparities in global coverage: Not only will vaccines help save lives and stabilise health systems, but they can help to drive a global economic recovery. That recovery cannot take place if half of the world is hamstrung from the economic fallout of Covid-19."

'Eerily similar to the HIV/AIDS epidemic'

The hoarding of medical supplies is neither novel nor unique to the coronavirus vaccine.

In 2009, the WHO had to grapple with the greed of rich countries buying up the H1N1 vaccine that inevitably tied up global supply and left the rest of the world without access. Prior to H1N1, there was the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

"Today's situation is eerily similar to the HIV/AIDS epidemic and crisis of access in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the diagnostic and therapeutic tools to save millions of lives were there but the will to share them was not," said Fatima Hassan, a social justice activist and human rights lawyer.

"Without the temporary TRIPS waiver now, countries will be required to take individual domestic action and legal measures - while managing a pandemic."

Sharifah Sekalala, an associate professor at the school of law at the University of Warwick, said the problem goes far beyond the question of intellectual property rights.

"Human rights have largely been ignored in arguments about vaccine rollouts and substituted for arguments of equity," Sekalala told MEE.

"This feels like a missed opportunity to really think about the vaccine as something that is fundamental to the right to life, health, but also access to wider social-economic rights given that ordinary life has been so constrained by this pandemic."

"I think it is safe to say that research and development contributed to a Covid vaccine would have been much less if it had been a disease that doesn’t affect developed countries as well and this of course would have meant that vaccines were rolled out slower," Sekalala said.

In the Middle East and North African countries, excluding Israel and rich Gulf Arab States, the prospect of a protracted pandemic may be unthinkable, but still very plausible.

Again, campaigners say the fight is still about accessing vaccines. Less is known about how to get the vaccines to places where there is a lack of food, barely functional health systems or governance.

"We know that over 53 percent of the population in Yemen is in need of humanitarian assistance; 16.2 million Yemenis rely on food aid to survive. So the crisis was already immense and completely unacceptable [even] before Covid," Mariott from Oxfam says.

"Unless we get vaccines to people, that suffering is going to escalate every day."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.