Egyptians risk all in deadly sea crossing to Europe

"We were just like sardines in a tin, one on top of the other."

Romany, a former wood supplier in Egypt, found himself boarding an unseaworthy boat measuring eight metres in length along with 48 others when he crossed the most dangerous sea border in the world: the Central Mediterranean.

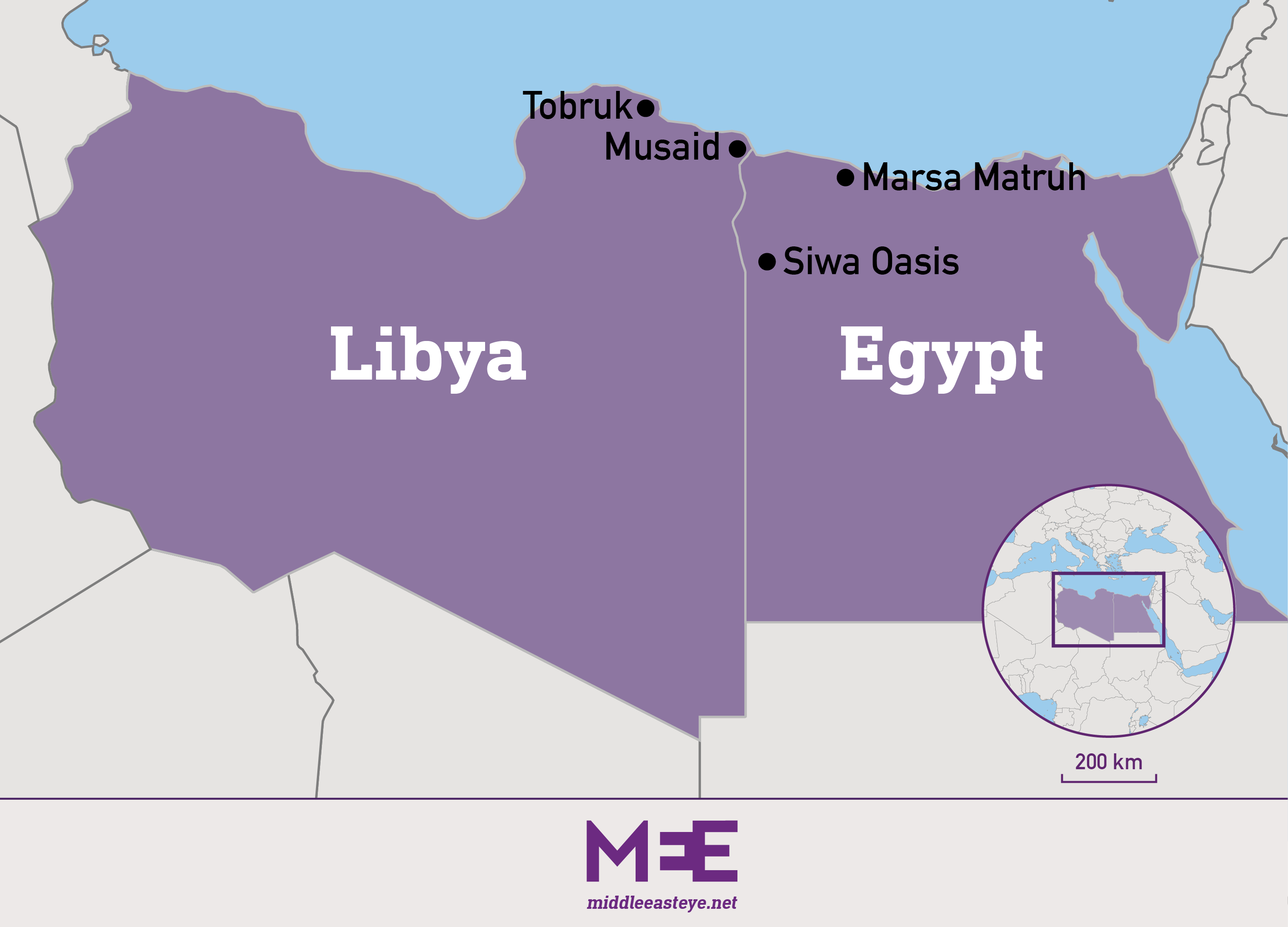

After his business went bust, and with a family of five children to feed, he sold everything he owned before crossing the border to Libya and then headed out to sea.

Middle East Eye spoke to Romany and two other men who had recently made the dangerous crossing from Egypt to Libya, and then to Italy.

They spoke from a small migrant shelter in Milan via Shukri*, an interpreter and Egyptian migrant himself.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"There was a moment when the waves were too high and then people really lost hope… they were saying their prayers," Romany told MEE.

'You need to be very lucky to be able to get the sort of smugglers that will not sell you'

- Hussein Baoumi, Amnesty researcher

"And now I'm in a shelter and looking for work… I have to work to get money to send to my children.

"I cannot return before at least securing my life."

The two other men, Mohamed and Ahmed, had met in a detention centre in Musaid, Libya, in August 2022. They had both come from the city of Abnub on the east bank of the river Nile in southern Egypt. Mohamed said he was fleeing a tribal vendetta, with blood feuds common in the poor, rural south.

Mohamed had managed to get a visa for Libya, while Ahmed resorted to a smuggling route and crossed the border by foot.

There was no respite on the Libyan side of the border, as the streets were lawless, gunshots filled the air and the threat of kidnapping loomed over them constantly. Mohamed threw his lot in with a smuggling network to get across the channel.

Prior to his departure, Mohamed was held for three months at a centre in the Libyan border town of Musaid, run by smugglers, and that is where he met Ahmed. The wait was excruciating, as it was haunted by the pervasive fear of police raids.

After months of waiting, they boarded a boat from Musaid in the dead of night. The rising sun revealed a decrepit shell measuring 25 metres in length, its rotten frame barely containing the 620 people aboard.

When they were far out at sea, the boat's motor failed and panic set in. Some of the passengers demanded they return, others that they push on. Fights broke out. Finally, the decision was made to turn back and drop 100 people back on the shores of Libya.

"There was mayhem," Mohamed recalled, "lots of us had been waiting for months in detention. People were shouting, I don't care if I die, I'm not getting out."

Surge in departures

These men's stories are not isolated incidents but part of a surge in Egyptians fleeing their country via smuggling routes, into the war-torn streets of Libya and across the Central Mediterranean in flimsy dinghies.

In February 2022, Egyptian arrivals in Italy peaked, accounting for around every 1 in 3 disembarkations in Italy.

According to the most recent data from the European Union's border agency Frontex, Egyptians were the most common nationality detected crossing the Central Mediterranean, accounting for 20 percent of the nationalities along the route over the first five months of 2022.

The three men sitting around an iPhone in a shelter in Milan were among the lucky ones who made it over a heavily militarised border and then across the deadly waters of the Central Mediterranean.

According to an IOM survey conducted between December 2021 and January 2022, most Egyptian migrants in Libya came from the country's northeast, mainly originating from the Governorates of Minya, Assiut, Fayoum, and Beheira.

Dire poverty ran through the stories like a thread. A cost of living crisis has eroded an already threadbare safety net in Egypt, plunging an estimated 60 million people below the poverty line and forcing many of them over the border into Libya.

Violence is also a driving factor. The Internal Displacement Monitoring centre has reported 1,000 new displacements due to violence in Egypt.

Human Rights Watch has documented the widespread use of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial executions as part of the National Security Agency's "war on terror".

In North Sinai, an eight-year-long campaign between Egypt’s armed forces and Sinai Province, the local branch of the Islamic State militant group, has generated a mounting death toll and the displacement of an estimated 100,000 of its 450,000 residents.

You have to be lucky

Ahmed, the younger of the three men in the centre, is just 20 years old. Like many migrants, he had to resort to smuggling rings to cross into Libya, paying the equivalent of $150 for his five-hour passage on foot over the porous border.

Amnesty researcher Hussein Baoumi spoke to Egyptians in Libya who had made the same journey, many of whom were young men from the poorest governates of Upper Egypt.

"You need to be very lucky to get a smuggler that will get you to Western Libya," Baoumi told MEE. "You need to be very lucky to be able to get the sort of smugglers that will not sell you."

Many of the men Baoumi spoke to ended up being detained by trafficking groups, some of whom were connected to armed groups that form what is referred to as the Libyan Arab Armed Forces, led by Khalifa Haftar.

I risked my life to get here, so I have to believe that life will be better here

- Ahmed, Egyptian migrant

"They have told me about [being] subjected to torture, being held in conditions that would be considered enforced disappearances and extortion. Of course, usually, the purpose of torture is to extract money from their families back home," he said.

There is only one official border crossing with Libya, the Mosaid-Salloum crossing, in the north. The Egypt-Libya border is vast but mostly impenetrable due to the terrain. The remaining northern 265km part is patrolled by Libyan and Egyptian militias.

Smuggling routes are often the only way to cross it. Since 2016, when several large boats were shipwrecked, the government has poured resources into securing their coastlines.

Flows of cash and support from EU states have bolstered the militarisation of the border, enabling heightened violence for the people attempting to cross it.

According to an investigation by Disclose, aerial surveillance supplied by the French air force, intended as terrorist reconnaissance, enabled aerial strikes against civilians suspected of smuggling activity.

The world's deadliest sea border

When Ahmed and Mohamed were stranded in the Central Mediterranean, they were encircled by a helicopter, but help took three days to arrive.

Since 2014, the Central Mediterranean has become the deadliest known migration route in the world, the site of an estimated 24,000 deaths.

The journey is long and often attempted in unseaworthy boats. Crackdowns on search and rescue missions have depleted their capacity. The sea border is also the site of the greatest number of migrant disappearances, with an estimated 12,000 people drowning or disappearing in the waters.

These "gaps" in search and rescue capacities have rendered the crossing a "black box", one that is, however, relentlessly patrolled and surveyed by EU-funded drones and aircraft manned by their border agency, Frontex.

These operations have directly correlated with a rising number of illegal interceptions by the Libyan coast guard and armed militia groups who act with impunity, often resulting in illegal "pushbacks".

A new decree introduced by Italian Prime Minister Georgia Meloni has added an extra layer of complexity to civil actors' increasingly fraught attempts to save lives in the Mediterranean.

The law compels rescue missions to disembark directly after a rescue, a restriction compounded by an existing policy that assigns SAR missions "distant ports" that often add days of navigation. This squanders precious time that could be spent patrolling the waters, depleting an already stretched civil fleet.

"Before the decree came into force, on average, we would do 4.5 rescues in one rotation," Caroline Wileman, the SAR deputy representative for Médecins Sans Frontieres, told MEE.

"On average, we would rescue more than 280 people and now we're rescuing 80 people. So the key question is, what is happening with those 200 people?"

I risked my life to get here

After three days adrift in the Mediterranean, Mohamed and Ahmed were rescued by the Italian coastguard.

They were then taken to a camp in Sicily where they were offered food and drink for the first time in days. "We felt an indescribable joy," Mohamed recalled, "we were shown our beds, but I would happily have slept in the street."

Huddled together in the room at the shelter in Milan, the joy they felt has now dissipated, but all three men said they were optimistic about the future.

"I risked my life to get here," Ahmed said, "so I have to believe that life will be better here."

Shukri, who has already spent 15 years here, knows a little better. "They don’t understand the difficulties here yet," he said wearily once the men had left.

He has had the time to become acquainted with an increasingly labyrinthine bureaucratic system that migrants in Italy are forced to navigate. Asylum seekers must wait 10 years before being eligible to apply for citizenship.

Shukri applied four years ago, but he is still waiting. In the meantime, he must pay to renew his residence permit, legal fees, and taxes.

"You have to pay everywhere in this country, it's not easy," he said. "Today, it's more difficult for them, because Europe is not available."

"If I return to Egypt, I will be thrown into a prison cell," Shukri told MEE. "I moved to this country for a fresh start, but after a few years, I’ve realised it has its own problems."

"Perhaps it is me!" he smiled wryly. "Perhaps the problems follow me."

MEE reached out to the Libyan foreign ministry and the Egyptian embassy in London for comment but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

*Names changed to protect identities

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.