Egypt: In shuttering a national icon, the government has unleashed rare public anger

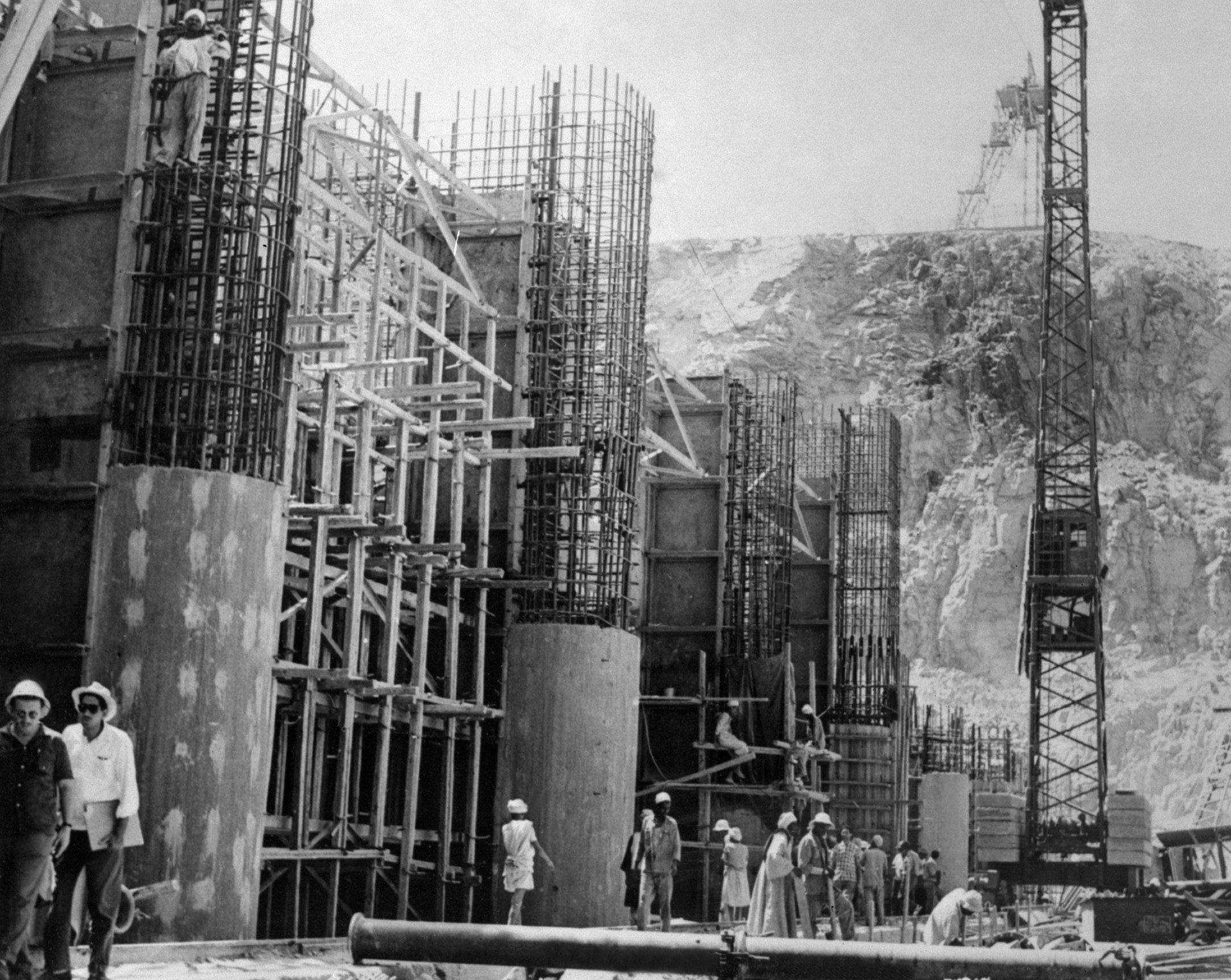

Its metal is woven into the Aswan Dam and its name is welded into Egyptian public memory. But now Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s government plans to tarnish the Egyptian Steel and Iron Company’s lustre, and wind up the major state-owned firm.

The threat to the company, founded by revolutionary leader Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1954 and involved in almost all major development projects since, has caused wide debate about the Egyptian government’s policy of shutting down major public businesses for the benefit of army-owned ones instead.

'The decision to wind up the company is made for the benefit of its competitors and we will not accept this'

- Gamal Saad, employee

With hundreds of thousands of tonnes of steel and iron in annual production, billions of Egyptian pounds in profits and thousands of workers in its different plants, the company is a national treasure and represents Nasser's unfulfilled dream of turning Egypt into a self-sufficient industrial hub.

But earlier this month, the Ministry of Public Enterprise Sector said the company would go into liquidation, close down its factories, and send its workers home for good.

The announcement has stirred rare and widespread public anger and criticism of the Egyptian government, expressed both inside the company and online.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Outpouring of anger

The ministry says the decision to send the company into liquidation boils down to persistent losses, accumulating debts and the lack of investors ready to pump cash to bring it back to life.

The cost of production at the company, it adds, has become far larger than the value of the production itself, which is translating into huge losses.

Nevertheless, the company's 7,500 workers are far from convinced.

"Our company has never made losses and our revenues equal expenditure in the worst of cases," Rida Mohamed, one of the workers, told Middle East Eye.

"The decision to wind up the company is made for the benefit of its competitors and we will not accept this," Gamal Saad, another worker, told MEE.

Mohamed, Saad and hundreds of others are staging demonstrations on a daily basis to express their anger and opposition. Protesting workers say they will leave the company only “over their dead bodies".

This anger is also seeping out of the company's walls and into the wider society.

Former MP Haitham al-Hariri warned against the effect the closure of the company would have on the amount of steel produced locally.

Scriptwriter and outspoken critic of the government Belal Fadl said the possible winding up reflects officials’ contempt for citizens.

The same debates are moving online, with ordinary people accusing the government of intentionally overlooking proposals for the upgrade of the company.

Ironically enough, the decision to liquidate the Egyptian Steel and Iron Company coincides with the anniversary of Nasser's birth.

Decline

As the backlash grows, the government appears keen to avoid responsibility by claiming the company’s general assembly has taken the decision, though many believe it inconceivable that the order wouldn’t come from the top.

Nevertheless, Public Enterprise Sector Minister Hisham Tawfiq said on 18 January that the decision to disband the company is "final".

"We will not allow a lossmaking company to keep living on money borrowed from the government," he said.

The Egyptian Steel and Iron Company’s debts have reached 8.5bn Egyptian pounds ($548m).

Its current production, the government says, is only 10 percent of its annual production capacity of 1.2 million tonnes.

'We will not allow a lossmaking company to keep living on money borrowed from the government'

- Hisham Tawfiq, public enterprise sector minister

The government cites a number of reasons for this drop in production, including outdated machinery, the breakdown of many of the company's plants and mismanagement.

The Egyptian Steel and Iron Company’s sad story is one of many examples of a production giant turning into a lifeless mass.

This company and others were part of Egypt's economic takeoff dream during the 1960s. But the dream turned into a nightmare because of mismanagement and corruption, economists say.

"The boards of the state-owned companies were an extreme failure over the years, despite repeated attempts by the government to put these companies on track," Khaled al-Shafie, head of local think tank Capital Centre for Research and Economic Studies, told MEE.

The Egyptian Steel and Iron Company's current annual production of 133,000 tonnes is only a fraction of Egypt's overall steel production of 11.8 million tonnes.

However, some people suggest foul play, especially as it comes at a time of widespread liquidations.

The Public Enterprise Sector Ministry works hard to turn state-owned companies from loss to profit, but it is also dissolving some firms, raising anger and doubts.

The ministry plans to disband the National Cement Company, one of the most important state-owned cement production centres, in June this year.

This follows the closure of some textile factories in the textiles hub of El-Mahalla el-Kubra and other cities.

These liquidations are costly, not only because of the loss of production, but also because the authorities will have to pay huge amounts of money to compensate the dismissed workers.

The government will have to pay 2bn Egyptian pounds ($129m) in compensation for the workers of the Egyptian Steel and Iron Company alone.

Some lawmakers have argued that upgrading and renovating the company and its facilities would require almost half this sum.

"The upgrade of this company would be much cheaper than its liquidation," MP Mohamed Badrawi, a member of the parliamentary Committee on Planning at the House of Deputies, told MEE.

MP Mustafa Bakri said the liquidation of public sector companies raises question marks, and he believes the government is lying about the steel company’s true condition. He vowed to present proof of this in the coming period.

The government, Bakri said, turned down offers by foreign investors to rescue the company.

"There is an apparent government desire for these companies to fail," he said.

The army moves in

As the government pulls the shutters down on state-owned companies and factories, many other businesses are being launched by the Egyptian army or by businessmen who partner with the military.

In November 2019, Sisi, the general-turned-president who won power in a 2013 military coup, opened a gigantic steel factory in the city of Suez. The factory is owned by the Egyptian army in partnership with a private investor.

In August 2018, Sisi opened his country's largest cement factory in the central province of Beni Suef. This factory is also owned by the Egyptian army.

These projects are just some of dozens of other schemes that are opening the door to accusations that state-owned projects are being closed down to hand the army total control of the economy.

The problem, economists say, is that the new projects cannot compensate for the loss of production caused by the closure of important factories, such as the steel company’s facilities.

"We need to protect these factories, not to close them down, if we really want to increase production and satisfy the needs of the local market," Shafie said.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.