Exporting America's gun problem? The proposed rule that has monitors up in arms

The Trump administration is on the cusp of changing small-arms export regulations that opponents say could flood conflict zones like the Middle East with the same retail guns used in mass shootings in the US.

The rules, which could be finalised this month, would allow sniper rifles, semi-automatic firearms and AK-47-style assault rifles to be sold commercially without requiring US companies to register with the State Department.

The State Department is required under the Arms Export Control Act to inform Congress of any arms sales worth $1m or more, a process which led lawmakers to block $1.2m in handgun and ammunition sales to Turkish security forces after President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's bodyguards beat up protesters in Washington DC in 2017.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

But the Commerce Department, which would now oversee the commercial sales of small arms, is not required to do so.

Last month, Democrats in both the House and Senate introduced legislation to block the proposed rules and would have had until Monday to intervene.

But Senator Robert Menendez (D-NJ), the ranking Democrat on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, placed a hold on the rules, telling Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in a letter that firearms and ammunition "should be subject to more, not less, rigorous export controls and oversight".

While Menendez's hold may extend discussion around the proposed rules, it is not legally binding and the Trump administration could brush aside his objection and implement the changes anyway.

Proponents of the rules, including the gun lobby, say this is a housekeeping exercise which started under the Obama administration to improve a bureaucratic export system and will keep US gun manufacturers competitive.

'We are putting our own service members at risk'

- Christina Arabia, Security Assistance Monitor

But arms monitors and human rights advocates say this is the latest instance after decades of gun deregulation and has the potential to fuel conflict, particularly through arms trafficking to third parties.

Earlier this year, a CNN investigation found that Saudi Arabia and the UAE had transferred US-made weapons to al-Qaeda-linked fighters in Yemen. In Iraq and Afghanistan, US troops have been fired on with American-made arms originally transferred to Iraqi and Afghan security forces.

“This is already a problem, and this is becoming a bigger problem,” said Christina Arabia, director at the Washington-based Security Assistance Monitor. “We are putting our own service members at risk.”

Arms monitors say the system currently in place to track US small arms once they are sold is already insufficient. Moreover, they emphasise that it's light weapons that are used in the vast majority of human rights violations worldwide.

“Things like small arms and light weapons – in sub-Saharan Africa, these are considered the weapons of mass destruction,” Arabia said.

Seth Binder, an advocacy officer at the Washington-based Project on Middle East Democracy, said: “This is just one more way that the US is sort of potentially fuelling regional conflicts and partners in the region [are] not being held accountable for actions.”

Philippe Nassif, Amnesty International's Middle East North Africa advocacy director, said loosening export requirements for these kinds of weapons "simply to bring in a few extra dollars is profoundly misguided and immoral".

"If these changes are in fact implemented, the Trump Administration - at a minimum - owes the American people an explanation as to how it will remedy the critical gaps that these changes introduce into the existing export control regime," he said.

Who has oversight

Currently, the State Department oversees the export of US-made military items ranging from firearms to tanks. Its control is considered critical to protect national security and items are listed on the US Munitions List.

Meanwhile, the Commerce Department has control of "less sensitive" exports with both military and commercial uses, like computers and radars.

The changes to the rules as proposed would move the commercial sales of items from three categories on the State Department's US Munitions List - small arms, artillery and ammunition - into Commerce's jurisdiction.

In 2017, the State Department approved $652m in commercial sales in these three categories to countries in the Middle East, according to figures compiled by the Security Assistance Monitor.

The top importers of US small arms were Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, which are among those recently ranked as the least transparent when it comes to small arms activities, according to the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey.

US manufacturers selling the items would no longer be required to register before exporting, including disclosing any fees, gifts or political contributions related to a deal. And unlike the State Department, the Commerce Department would not be required to notify Congress of commercial sales over $1m.

Proponents like Kevin Wolf say the move will streamline the export of commercial weapons that should never have been grouped with military items in the first place.

Wolf is a former Commerce Department official who wrote the proposed rules during the Obama administration and has worked as a legal adviser for the National Shooting Sports Foundation, a gun industry group which has pushed for the change.

'You are going to get the same answer in terms of approval or denial that you would under State'

- Kevin Wolf, former Commerce official and gun industry group adviser

He says the change will allow the State Department to focus on “transactions of concern” rather than a one-size-fit-all approach to everything being sold.

“A washer or a switch or adaptor for a military aircraft had exactly the same military controls as the aircraft,” Wolf said.

Under the new rules, he said, all applications for exports will still be reviewed by the Defense Department and the State Department, a point both the State and Commerce departments confirmed to MEE.

A congressional aide, speaking on condition of anonymity, told The Hill last week that the Commerce Department might consult with the State Department, but would make the final decision. "One of the reasons for doing this is fundamentally for export promotion, to make it easier to traffic these arms abroad," the aide said.

But Wolf said the new process won't change the outcome. “You are going to get the same answer in terms of approval or denial that you would under State, but it would be done in a manner that’s easier for commercial exporters,” he said.

The proposed rules were, in fact, ready to be published during the Obama administration, Wolf said.

But then, on 14 December 2012, a 20-year-old shot and killed his mother and 26 students and faculty at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, and then shot himself. The attack is one of the deadliest in US history.

“I made the decision to not publish the rules because of the optics,” he said. “The two were completely unrelated, but not everyone is an export control expert ... I didn’t want people to get distracted by the larger gun policy debate.”

Every few months after the attack in Sandy Hook, Wolf said, there were more shootings and, by the time the Obama administration was coming to an end, time had run out.

Unsurprisingly, arms monitors dispute Wolf’s narrative. “So you are saying that the US has a gun problem so you halted the exporting of it, but now is a good time?” Arabia said.

The changes, monitors say, are not export housekeeping, but are rather the result of years of efforts by the gun lobby to expand sales abroad. While small arms may be sold with ease in US gun shops, they are the same weapons often used in civil conflict and criminal violence around the world.

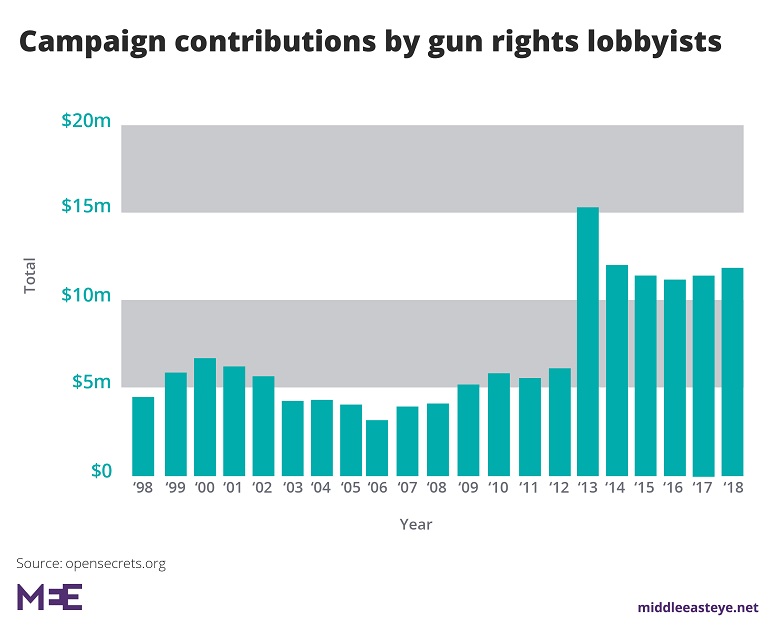

“It’s an enormous accomplishment for [the gun lobby],” said Aaron Karp, a senior lecturer in political science at Old Dominion University in Virginia and senior consultant to the Small Arms Survey. “It’s the result of a highly organised effort.”

Binder with the Project on Middle East Democracy said both the Obama and Trump administrations, as well as the State and Commerce departments, have consistently said the change isn’t deregulation.

“Folks in our community have disagreed with that. Former government officials have been on record saying it is, in fact, deregulation," Binder said.

"I think that can be debated. But what I can say is that there are loopholes that develop in Commerce that don’t exist in State.”

Already in the dark

Foremost among their concerns is how the US government will keep track of the firearms, ammunition and other components once they are sold.

Right now, once commercial sales of small arms are approved, only the final authorised sale and general category of the type of weapons involved - not a specific, itemised breakdown - are shared publicly at the end of the fiscal year.

When the weapons are delivered, which can be years after a sale is made, only the value of what is delivered is publicly disclosed, not what has arrived in a country.

“So in other words, you don’t even know what exactly is eventually sold, and then you don’t know when it’s delivered to that country,” said Arabia.

The State Department currently monitors arms after sales are complete with a programme called Blue Lantern. But arms monitors say it’s ineffective and it is unclear what the monitoring plan will be at the Commerce Department.

As of 2017, the programme was run by embassy staff in countries to which weapons were sold, with only five State Department employees and four contractors, according to Blue Lantern's 2017 annual report for Congress.

According to the same report, out of 36,092 approved arms export licence applications, only 429 - or 1.2 percent - were investigated by Blue Lantern.

“They are completely understaffed,” said Arabia. “It’s such a small percentage of actual arms shipments that they can follow up on in a year, and the reporting on that is ridiculous.”

MEE asked the Commerce Department how it specifically planned to monitor the commercial items moving over from the State Department and whether the system would be as thorough as Blue Lantern.

A spokesperson directed MEE to a 2018 press release, highlighting a section which said that the government would “continue its longstanding end-use monitoring effects”, but gave no further detail about how Commerce planned to monitor arms.

There are also worries over potential changes related to US private security contractors.

Currently, contractors are required to obtain a licence in order to train foreign forces on how to use weapons on the US munitions list. The new rules, say arms monitors, may create a loophole, allowing contractors to provide military training without obtaining a licence so long as firearms are not exported for the training.

Arabia and Colby Goodman, a Maryland-based independent arms control expert formerly with the Security Assistance Monitor, hired a pro-bono lawyer to try to understand the potential changes.

A State Department official told MEE that whether a firearm was involved or not, trainings that require licences will still need them “so we’d view this argument as inaccurate”.

But Goodman said he believes the rules could open up the types of services that contractors can do without US government oversight, for example training on issues like intelligence, military organisation and interrogation, so long as they aren’t using or providing exported weapons.

"It could be a scenario that the US government did not know that the US firm was providing this training, and let's say individuals get involved in some shady activities and it appeared as if the US was involved somehow because it's former US personnel," said Goodman. "That could really elevate into a diplomatic problem."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.