Is France's response to Samuel Paty murder deepening divisions?

A week after the gruesome murder of a schoolteacher in a Parisian suburb, France remains in shock and mourning.

Samuel Paty, a 47-year-old history teacher at a middle school in the town of Conflans Saint-Honorine, was decapitated on 16 October by 18-year old Abdullakh Anzorov, a Russian-born refugee of Chechen descent. Anzorov was later shot dead by French security forces.

The attack took place after Paty became the target of a campaign calling for his dismissal after he showed his students a caricature of the Prophet Muhammad during a class on freedom of expression.

In the wake of the horrendous crime, the French government has been quick to announce the deployment of a host of measures, with President Emmanuel Macron declaring that "fear must change sides".

From the six-month closure of a mosque accused of having shared a video critical of Paty, to the deportation of undocumented foreigners suspected of “radicalisation”, French officials have adopted a martial rhetoric seeking to project toughness in the face of attacks motivated by Islamic State (IS)-inspired ideology - with members of the political scene calling for ever more stringent measures to combat “separatism”.

Some five years after the deadly Charlie Hebdo and Bataclan attacks, France finds itself once again embroiled in a public debate on the fight against terrorism and the definition of the country’s very particular brand of secularism, laicite.

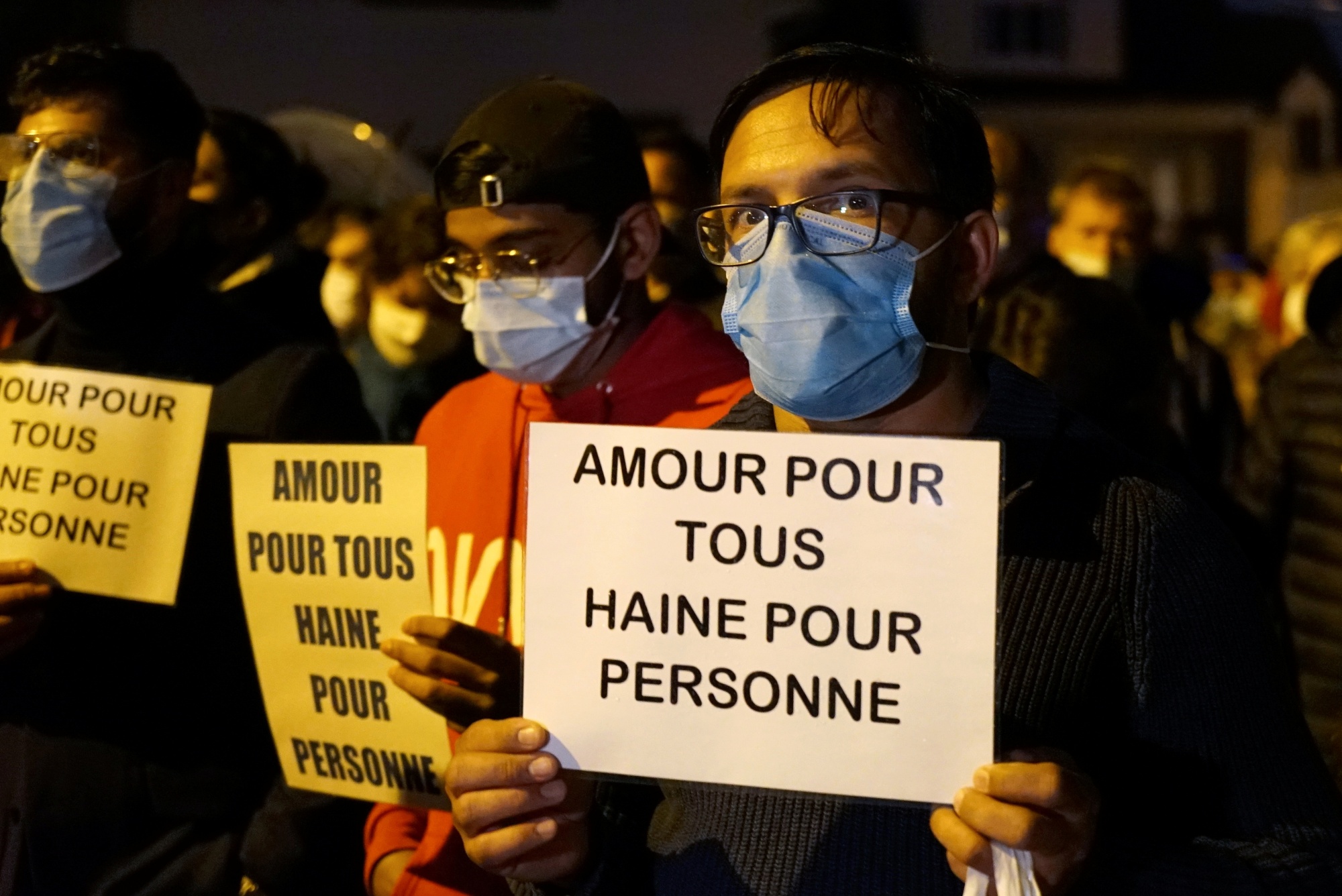

For many in Muslim communities that has raised apprehensions about a further conflation of Islam and Islamist extremism, as some advocates warn that an aggressive, indiscriminate approach may only play into the hands of the very people the government seeks to fight.

“Faced with a terrorist enemy, French people are completely traumatised, and have been traumatised on several occasions,” Dounia Bouzar, an anthropology researcher studying Muslim communities in France, told Middle East Eye, expressing fear that the current climate will lead “one terrorism to feed another”.

Deploying an arsenal

Seven people have been indicted in connection to the attack, including a parent who had launched the campaign against Paty over the caricature.

Macron announced on Wednesday that the Cheikh Yassine Collective, a Salafi pro-Palestinian organisation, was meanwhile dissolved for being “directly implicated” in the attack, after its founder, Abdelhakim Sefrioui, was arrested for participating in the campaign launched by the parent.

Sefrioui has denied having any knowledge that an attack was being planned.

Macron’s cabinet has been described by Le Monde newspaper as using “all manner of means” in order to show the French public it is reacting decisively to the attack, even if the effectiveness or relevance of some measures have been questioned.

French interior minister Gerald Darmanin has led the offensive, vowing on Monday that there wouldn’t be “a minute of respite for the enemies of the Republic”.

In addition to the investigation into Friday’s murder, a series of hardline measures have been announced.

As well as the Pantin mosque closure, increased police raids and the planned expulsion of 231 foreign nationals accused of promoting extremism - a move which had been underway prior to Paty’s killing - Darmanin has expressed his determination to shut down a number of organisations, most prominently Muslim charity BarakaCity and the Collective Against Islamophobia in France (CCIF), which compiles information on alleged acts of anti-Muslim hatred in the country.

Translation: I will propose the dissolution of the CCIF and BarakaCity, associations that are enemies of the Republic. We must stop being naive and look at truth straight on: there is no accommodation possible with radical Islamism. Any compromise means becoming compromised.

Bouzar cautioned against calls to close such organisations, saying proper investigations needed to be done to determine any wrongdoing lest it turn into “a crime of opinion”.

“You can agree or disagree with them… but to dissolve them means exiting the rule of law,” she said. “Or else, we have to ban all communitarian movements, like the Lubavitch, Mormons, the CRIF (Representative Council of French Jewish Institutions)...”

Muslim-affiliated organisations haven’t been the only ones in the authorities' crosshairs in recent days. The general rapporteur of the government’s own Observatory of Laicite, Nicolas Cadene, is reportedly under pressure to be replaced.

According to magazine Le Point, Minister Delegate in charge of Citizenship Marlene Schiappa has long been unhappy with Cadene’s public positions denouncing Islamophobia, with one source saying that the rapporteur “seems more preoccupied by the fight against the stigmatisation of Muslims than by the defence of laicite”.

Punitive one-upmanship

Meanwhile, Darmanin went one step further on Tuesday by expressing the view that the existence of halal food sections in stores encourages Muslims to isolate from the rest of French society.

“It’s always shocked me to enter a supermarket and see an aisle of communitarian cuisine on one side… that’s my opinion, this is how communitarianism starts,” the minister said.

“I think capitalism has a responsibility. When you sell communitarian clothing, maybe you have a part of responsibility in communitarianism.”

“So are you saying you would like to see these things disappear?” the interviewer asked.

“I have my opinion, and fortunately not all my opinions are part of the laws of the republic,” Darmanin answered.

While his comments have raised eyebrows, the interior minister is far from an anomaly in the French political and media landscape.

On CNews channel, which has been described by some as the French Fox News, several political and media figures suggested on Monday a flurry of radical, yet oft-repeated, measures to tackle the perceived war on French secular identity. These included opening a prison colony on the Kerguelen Islands in the Antarctic circle, and cracking down on first names that do not have French origins.

Meanwhile, French MP Meyer Habib, who represents French citizens living in southern Europe, Israel and Turkey, quoted the French national anthem in a tweet with thinly veiled allusions to armed conflict.

“Take up weapons, children of the fatherland!... they are coming into our midst to cut the throats of your sons and consorts’... Anger. We must wake up! It’s almost too late," he wrote on 16 October, before calling the next day for the deportation of undocumented migrants, the implementation of administrative detention, and the revocation of nationality for those convicted of terrorist acts.

For Yasser Louati, president of the Committee for Justice and Freedoms for All (CJL), the aggressive rhetoric used by Darmanin and others is concerning.

“When we talk about ‘enemies within’, this term was first used against Jews, ending in the catastrophe that we know of,” he told MEE.

“Never after an attack has [the government] asked ‘why?’ Never has the state done an audit of the failures of anti-terrorism measures after an attack. We keep things as they are, even if they are failing, and we call for new laws. Never has the executive branch asked that we all stand up against this together.”

Laicite, the eternal debate

The murder of Samuel Paty has once again brought to the fore France’s tensions over the meaning and application of laicite, a cornerstone value of the state for over a century.

First enshrined into law in 1905, and mentioned in the first sentence of the constitution, laicite is legally defined as the strict separation of state and religion. In the past two decades, however, a new interpretation has gained ground, which sees expressions of faith in public spaces as contrary to France’s secularist values.

While secularism in principle applies to all religions equally, Islam has been singled out by the new conception of laicite, with head coverings such as the hijab or niqab being subjected to legal restrictions due to being deemed ostentatious religious symbols.

The rise of IS, which recruited hundreds of French members who went to Syria and Iraq, along with several prominent attacks carried out in France by followers of a similar ideology, has further strained the terms of the debate.

Since the deadly attack on satirical publication Charlie Hebdo by two members of al-Qaeda in January 2015 following its publication of caricatures of Muhammad, more than half of French people polled have said they believe Islam to be incompatible with French values.

Growing resentment against Islam has left Muslims “to feel like they have to choose between their country, France, and their religion - as if a choice had to be made,” Bouzar says.

Earlier this month, Macron had announced plans to present a draft law aimed at strengthening secularism in France and tackle what he described as "Islamist separatism" in the country, calling for increased government oversight over the financing of mosques and training of imams.

While France forbids census figures based on race or religion, Muslims are believed to represent around six million of the country's 67 million inhabitants, many of whom have origins in former French colonies in Africa.

The topic of Islamophobia has been a longstanding issue in France, with analysts arguing that the intersection of immigration, religion and class have meant many French Muslims suffer from poverty, discrimination, and marginalisation within French society.

Macron himself acknowledged during his 2 October speech on separatism that the French state bore responsibility for the “ghettoisation” of poorer areas and the rise of exclusionary ideologies.

“We have concentrated populations together based on their origins, we haven’t sufficiently recreated diversity, not enough economic and social mobility… on our retreat, our cowardice, they [extremists] have built their projects,” he said.

‘Muslims are scared’

The state’s simultaneous crackdown on violent ideologies exemplified by groups such as IS and al-Qaeda, as well as expressions of Muslim faith such as head coverings or other modest attire, has led to a conflation between the two, some advocates say - even though French Muslims have also found themselves the targets of ideologically motivated violence.

“Muslims are doubly scared,” Bouzar said. “They are afraid of jihadists who want to eliminate them because they are not ‘true’ Muslims, and then they are scared of this anti-Muslim hatred which changes their daily lives.”

'We are all targeted by terrorism. Terrorism makes no differentiation between Muslims and non-Muslims'

- Yasser Louati, Committee for Justice and Freedoms for All

For Louati, the dichotomy made between Islam and laicite ends up working in the favour of groups like IS, often referred to by its Arabic acronym Daesh in French.

“When Daesh wrote in 2014 about ‘destroying the grey area’, they said: ‘We want to spill blood and divide Western society to make Muslims an oppressed community,” he said.

“We are all targeted by terrorism. Terrorists make no differentiation between Muslims and non-Muslims - they’ve shown it at the Bataclan, they’ve shown it at Charlie Hebdo, they’ve shown it in Nice.”

In the wake of the Conflans murder, several attacks with suspected anti-Muslim or anti-Arab motives have been reported in the country, most notably a stabbing attack targeting two veiled women near the Eiffel Tower in Paris on Saturday.

“France is experiencing psychological trauma, but to lose complexity in our analysis is dangerous,” Bouzar said. “It means losing our values, mirroring perhaps Daesh. It’s not a matter of self-righteousness, it’s that it could be counter-productive.”

Bouzar worked for the French government in 2017 on a project seeking to deradicalise Islamic State sympathisers or former members.

Under then-Prime Minister Bernard Cazeneuve, she said she was able to take a multidisciplinary approach bringing together psychologists, families, schools, imams and police to go to the root of the issue.

She believes French authorities need to come back to a complex approach, instead of relying exclusively on a “repressive system”.

Some of the young people she sought to rehabilitate, she said, are now “under the impression that they will never have a place in France”.

Concerns over legality

In addition to fears that the response to the murder of Samuel Paty will further stoke resentment against France’s Muslim community, legal experts have cautioned that the government’s aggressive approach may in effect violate existing French and international law.

Speaking to France Inter radio on Tuesday, legal expert on public freedoms Nicolas Hervieu cautioned that despite the “race” to announce firm measures, many such decisions could end up being contested in court if they did not go through due process.

“We cannot dissolve an association simply because we don’t agree with its opinions,” Hervieu said, adding that investigations had to take place on a case-by-case basis.

“There could be a paradox in how, faced with the vital menace which Islamist terrorism represents to our democracy, we end up undermining ourselves the foundations of democracy by putting an end to the freedoms that are our pride and against which terrorists fight.”

'Blanket characterisation of the enemy is... one of the ingredients of totalitarian thinking, for jihadists as well as for fascists'

- Dounia Bouzar, anthropologist

International rights groups have called for human rights to remain at the centre of the response to Paty’s execution.

“One does not fight hatred with hatred. One does not fight intolerance with more intolerance... Human rights protect us. We must protect them,” Amnesty International wrote in a statement honouring the slain teacher.

The perspective of breaching the law has not appeared to faze some political figures, regardless of affiliation.

Former French Prime Minister Manuel Valls seconded on Sunday Damarnin’s call to shut down BarakaCity and the CCIF - even if it meant breaking the law.

“If we must, in an exceptional moment, distance ourselves from European law, make our constitution evolve, we must do so,” he told BFMTV. “I’ve said it before in 2015, we are at war. If we are at war, then we must act and strike.”

On Tuesday, the CCIF announced that it had appealed to the United Nations Human Rights Council over the “separatism” bill and efforts to shut down Muslim associations, calling the context an “unprecendented situation in France regarding the treatment of Muslim communities”.

This wouldn’t be the first time that an international rights body has looked at France's relationship with its Muslim communities.

In the past several years, UN human rights rapporteurs have repeatedly denounced France’s state of emergency and surveillance policies as straying from Paris’s “international commitments and obligations in terms of human rights”.

In 2018, the UN Human Rights Committee said France’s niqab ban “disproportionately harmed” freedom of worship, adding that it was “not persuaded by France’s claim that a ban on face covering was necessary and proportionate from a security standpoint or for attaining the goal of ‘living together’ in society”.

Is a nuanced, measured debate on Islam and secularism still possible in France today? Bouzar is pessimistic.

“In this context, it’s very complicated,” she said. “I have spent my life trying to create a connection between Muslims and non-Muslims, and now… it’s a catastrophe.

“The blanket characterisation of the enemy is part of all ideologies that lead to violence. It’s one of the ingredients of totalitarian thinking, for jihadists as well as for fascists.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.