France riots: For racist police, Arab, Black and Muslim lives do not matter

On the eve of the most observed Muslim celebration, Eid al-Adha, Nahel Merzouk, a French teen of Algerian and Moroccan descent, was brutally murdered by a police officer during a traffic stop.

At first, the police described the event as a case of legitimate self-defence. To their disarray, the scene was filmed and proved the fallacy of the official version. It proved Nahel never threatened in any way the officers’ lives.

He was shot at point-blank range when he tried to escape. The video was shared on social media and instantaneously became viral, sparking a wave of outrage across the entire country only hours after the murder took place.

While busily preparing for a blissful religious event, French Muslims’ spirit abruptly shifted from joy to grief.

Uprisings began to unfold in Nanterre, the scene of the killing. The following night, they reached the rest of the country. The protestors targeted state institutions: all across the country, they burnt down town halls, attacked police stations, and vandalised some schools. They looted shops and supermarkets.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Remarkably, most of the protestors involved in the rioting are in their teenage years. To oppose them, the state has used draconian counterinsurgency methods.

From Thursday night onwards, the Ministry of the Interior deployed 45,000 police officers. The use of military weaponry - including tear gas and armoured vehicles - is normalised to pacify the rioters. Hundreds were arrested. The courts pronounced the first fast-tracked prison sentences this weekend.

These riots are a clear expression of frustration and anger over a blatant injustice.

The protestors regard the state - and its institutions - with clarity: they see it as the main culprit responsible for their suffering. The riots are a form of political dissent expressed by a generation of Muslims and non-white teenagers whose lives are deemed inferior, cheap, and meaningless by the French state.

Systemic brutality

France has a history of Islamophobic and racist murders committed by the police.

Since 1991, at least 21 violent uprisings of varying sizes broke out following a racist crime committed by the police. In 2022 alone, at least one man of African descent died at the hands of the police every month.

This brutality finds its roots in France’s colonial past: law enforcement’s function was submitting the indigenous Muslim population to "the Republic’s values", preventing the legitimate expression of their political dissent.

Current police forces have inherited this role in a different context. Police brutality is a systemic issue with specific political goals: it is the means the French state uses to protect republican values and violently obstruct Muslims and ethnic minorities’ political growth.

Police brutality and murders are not events of marginal significance, or an abhorrent exception to common good practice. Police brutality is the norm in Muslim neighbourhoods.

On Friday, the spokesperson of the UN's Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Ravina Shamdasani, said in a statement of concern over the death of 17-year-old Nahel. "This is a moment for the country to seriously address the deep issues of racism and discrimination in law enforcement," she said.

The legislation regulating police practices was designed with the intent of protecting its Islamophobic and racist function. It is shaped to protect police immunity, giving police officers a free hand when addressing Muslims and non-whites.

In the case of Nahel’s murder, the relevant law - regulating the use of fire weapons by the police - was passed in 2017 amidst a strong Islamophobic push to loosen the legal framework regulating police intervention in Muslim-majority neighbourhoods. Critics believe it granted the police a "licence to kill".

An intoxicating atmosphere

A police crime committed on the eve of Eid does not explain alone the significant magnitude of the riots.

It should be contextualised within France’s current state of affairs to understand the motives animating so many young French citizens. Indeed, the country is home to an intoxicating Islamophobic and racist atmosphere.

Islamophobia is at the core of the French political discourse: the criminalisation of Islam and Muslims has become mainstream.

As evidenced by a testimony given to a town councillor, deep-rooted Islamophobia provided the fertile ground for violence: "Listen, that's it, they're criticising our religion, they think we're illiterate, that we're scum, that's enough."

French media and politicians engaged in a common practice of character assassination of the victim by suggesting a criminal past. This narrative is meant to belittle the gravity of his murder. Power structures systematically use this tactic to relativise the state’s heinous crimes.

The victim’s profile is irrelevant in these cases. Delinquency does not justify death at the hand of law enforcement agencies. This dehumanising narrative targeting a murdered child alienates French citizens of Muslim and non-white backgrounds even further.

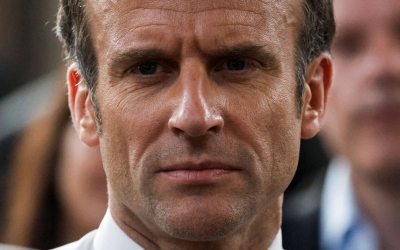

As the riots went on, media and politicians tried to depict the uprisings as a manifestation of a moral and educational crisis, denying their political nature. French President Emmanuel Macron appealed to the parents’ sense of responsibility.

According to this second narrative, violence was not the natural answer to grave injustice, it was the incomprehensible behaviour of children due to their parents' lack of care and education.

Instead of trying to understand the legitimate political grievances expressed through violence, both narratives shamed and blamed the victims of the state’s Islamophobia and racism. They served as violence’s catalyst, fuelling the rioters’ frustration and determination.

Police abolition

This entire picture illustrates the consequences of state-led dehumanisation of a segment of its population.

Denying their right to safety, their grievances and their political expression, and curtailing their fundamental rights proves how much the French state despises their existence.

The state's crackdown will soon stop the riots, but it won’t change the protestors' spirit in the long term as its root causes persist

Arab lives, Black lives, and Muslim lives do not matter. They can be trampled on and stolen at will.

A way out is still possible.

Reforming the police is unrealistic, as proven earlier. Its function is Islamophobic and racist. Furthermore, more than half of its members support far-right parties, therefore, only its complete abolition could lead to a systemic change.

The young rioters’ anger is a predictable response to a disturbing murder. The state's crackdown will soon stop the riots, but it won’t change the protestors' spirit in the long term as its root causes persist.

As Frantz Fanon wrote in The Wretched of the Earth: "The repressions, far from calling a halt to the forward rush of national consciousness, urge it on".

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.